Dear Classical Wisdom Reader,

It’s something that still surprises people.

The Iliad, ancient Greece’s famous epic poem centered on the Trojan War, does not feature the Trojan Horse.

The famous sack of Troy is never depicted within it either. Without getting into spoilers (for a millennia old poem!), the ending of the Iliad essentially sets the stage for the destruction of Troy, but the action cuts off before it actually happens.

It’s similar to how violence takes place in Greek tragedy. Whenever some bloody deed has taken place, a messenger appears and relates the story to the other characters. The violence itself always happens off-stage.

The Romans, however, were not like that.

Roman literature has a tendency to be more openly violent than that of the Greeks, with the Aeneid, for instance, featuring a notably lurid and detailed depiction of the fall of Troy.

Where the Greeks were silent, the Romans were loud.

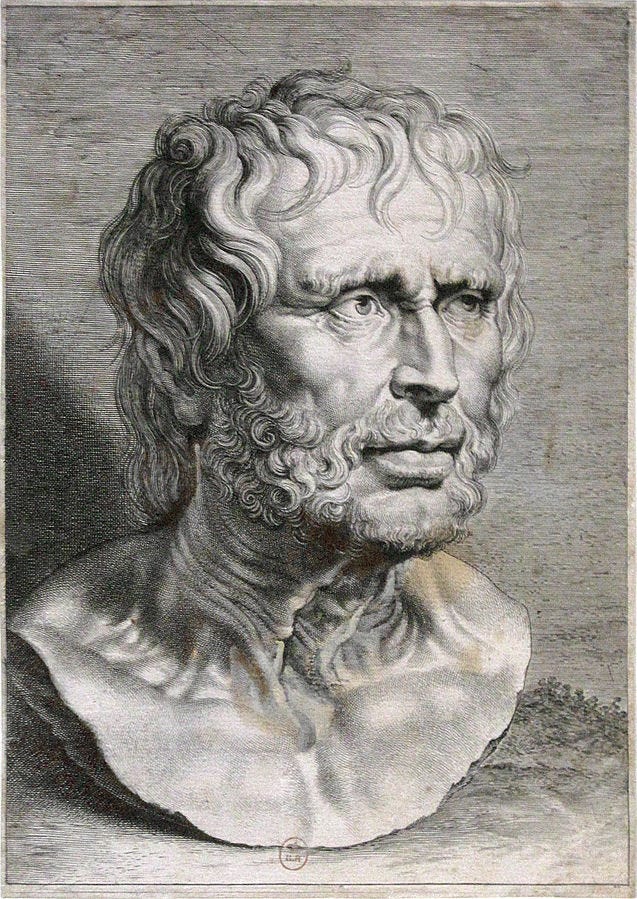

It’s typical of Roman literature, even including the plays of the celebrated statesman and Stoic, Seneca. Despite being a Stoic, his plays feature some very bloody scenes.

Today’s guest article from Andrew Perlot at Socratic State of Mind looks at Seneca’s tragedies, and asks if there is a method to the madness…

Is it possible the philosopher was trying to sneak in some philosophical ideas under the guise of crowd-pleasing violence?

And what does it tell us about the man himself?

Maybe it’s all a very different kind of Trojan Horse, after all…

All the best,

Sean Kelly

Managing Editor

Classical Wisdom

Seneca’s Trojan Horse

by Andrew Perlot of Socratic State of Mind

Why did a Stoic like Seneca spend so much effort writing violent, angst-filled dramas?

During the philosopher’s lifetime he was best known as Emperor Nero’s chief advisor and speechwriter, and as a virtuous Stoic whose works were widely read by the well-educated.

But Seneca was a polymath who dabbled in two surprising sidelines: proto-scientific thinking and writing bloody tragedies.

Moonlighting as a proto-scientist made sense. Ancient Stoics believed nature had ethical implications, and Seneca weaves philosophical points into his investigations in his book, Naturales Quaestiones. He didn’t see science as a separate topic so much as an extension and explication of Stoic philosophy.

But the incredibly violent plays? There was no shortage of people accusing Seneca of hypocrisy in his lifetime and in subsequent eras, and we might conclude that he was violating his own philosophical advice.

Seneca wasn’t a believer in the edifying properties of violence. For instance, he thought Rome’s popular gladiatorial games degraded those who watched them:

“There is nothing so ruinous to good character as to idle away one's time at some spectacle…Why do you think that I say that I personally return from shows greedier, more ambitious and more given to luxury, and I might add, with thoughts of greater cruelty and less humanity...Do not, my Lucilius, attend the games, I pray you. Either you will be corrupted by the multitude, or, if you show disgust, be hated by them. So stay away.” — Seneca, Epistles, 7.3-4

So why did a man disgusted by the violence, cruelty, and passions of his age create fictitious representations of it?

A Stoic Shakespeare

Whatever the moral and philosophical implications of drama, Seneca knew how to write a crowd-pleaser. His works are mostly forgotten today, but he was probably the greatest playwright of his age, producing at least eight tragedies and one satire.

The orator and literary critic Quintilian, who disliked Seneca’s writing style, wrote that in his youth, “Seneca's works were in the hands of every young man.”

It’s unclear if the plays were only recited aloud or were acted out on stage, but they made a splash beyond Rome’s elite. Seneca’s name is scrawled (misspelled) on a building wall in Pompeii, as if by an adoring fan. Another wall in the same city has a line from his play Agamemnon.

It’s possible that far more Romans encountered Seneca’s dramatic stories than ever read his philosophical ideas, which may have played into his choice to put so much effort into them.

Senecas’s Literary Style:

Seneca’s plays have a distinct style. He’s antiquity’s mashup of Shakespeare and Quentin Tarantino, and you shouldn’t pick up one of his plays looking for a happy ending.

His tales are filled with ill-fated heroes and gods using soliloquies to vent their rage at fate’s cruelty. Repeatedly we see the misuse of power, violence begetting violence, a lack of positive divine intervention, and the fragility of order and civilization. There’s lots of blood and death, and even a bit of cannibalism.

Seneca knew his countrymen adored violence. Nothing was more likely to draw them in. The question is, could he use that to achieve a good end?

What Seneca Was Trying To Do:

The plays and hero myths of antiquity were popular among philosophers and considered valuable teaching tools. The Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius quotes several Greek plays in his journal, Meditations. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, lauded Odysseus for cheerfully submitting to Fate without surrendering his initiative.

Yet poets and playwrights could deceive their audiences by glorifying vice. Plato lambasts Homer for this very reason. Achilles follows rage and revenge to the shores of madness and does unspeakable evil, but one might walk away from the Iliad thinking him a noble exemplar to follow. If Alexander the Great is any indication, many did.

So it’s notable that most of Seneca’s plays re-imagined mythological stories by shoring up their moral lessons.

Getting the Psychology Right:

In Euripides’ version of Medea — written 500 years before Seneca’s, but still very popular in Rome — the Greek playwright has his titular character murder her innocent children after being wronged by her husband Jason, and explain,

“I understand what evils I am about to do,

But passion is stronger than my counsels,

Passion that is responsible for the greatest evils for mortals.”

But Stoicism insists no person knowingly does evil; evil results from faulty reasoning. So Seneca’s Medea isn’t evil against her will, but rather simply wants justice. Medea is blinded by fury and reasons poorly (as angry people do), but she’s convinced murdering her children with Jason is revenge proportional to the crime committed.

Seneca’s Medea makes a mistake rather than willfully deciding to be evil.

Getting Clear on Passion:

For Stoics, passion is a misleading force in the mind arising from failure to reason correctly, and horrible things result from it. Seneca wants to make this abundantly clear, so his tragedies hijack the popular, older Greek plays and move the horrors of passion to the forefront. Titillating violence and familiar stories drew the crowd, but once they were hooked, he would make sure they understood.

After watching passion destroy lives, families, and societies, few people would walk away from one of Seneca’s plays without being deeply disquieted.

An awareness of the dangers of passion might be enough of an accomplishment, but Seneca probably hoped this opened the audience up to doing philosophical work to defuse their passions, overcome vice, and find eudaimonia (a ‘good flow of life’, ‘thriving’, or simply ‘happiness’)

Saying What Couldn’t Be Said:

I think there’s one more speculation we might make: Seneca used at least some of his tragedies to do what he dared not do elsewhere: explore himself and his mistakes.

Emperor Nero became increasingly despotic as he grew to adulthood. Seneca couldn’t control him, but the princeps wouldn’t let Seneca go: he was too valuable. Nero learned he could use Seneca’s reputation for virtue to shield him from the consequences of his misdeeds, such as killing his mother, wife, and stepbrother. Seneca didn’t speak out and may have actively colluded, giving him a reputation for hypocrisy he couldn’t shake.

The situation must have haunted Seneca, but he couldn’t tell anyone or write about it. Those who criticized Nero were killed or ordered to commit suicide. Sometimes their families were forced to join them in death.

For this reason, Seneca’s philosophical texts are weirdly devoid of Seneca. Though he must have had crazy stories from his life at court, he sticks to safe domestic tales. One gets the sense that Seneca was holding back.

But Seneca’s tragedies allowed him to wrap his moral lessons up with a camouflaged version of his own life and say what couldn’t be said directly.

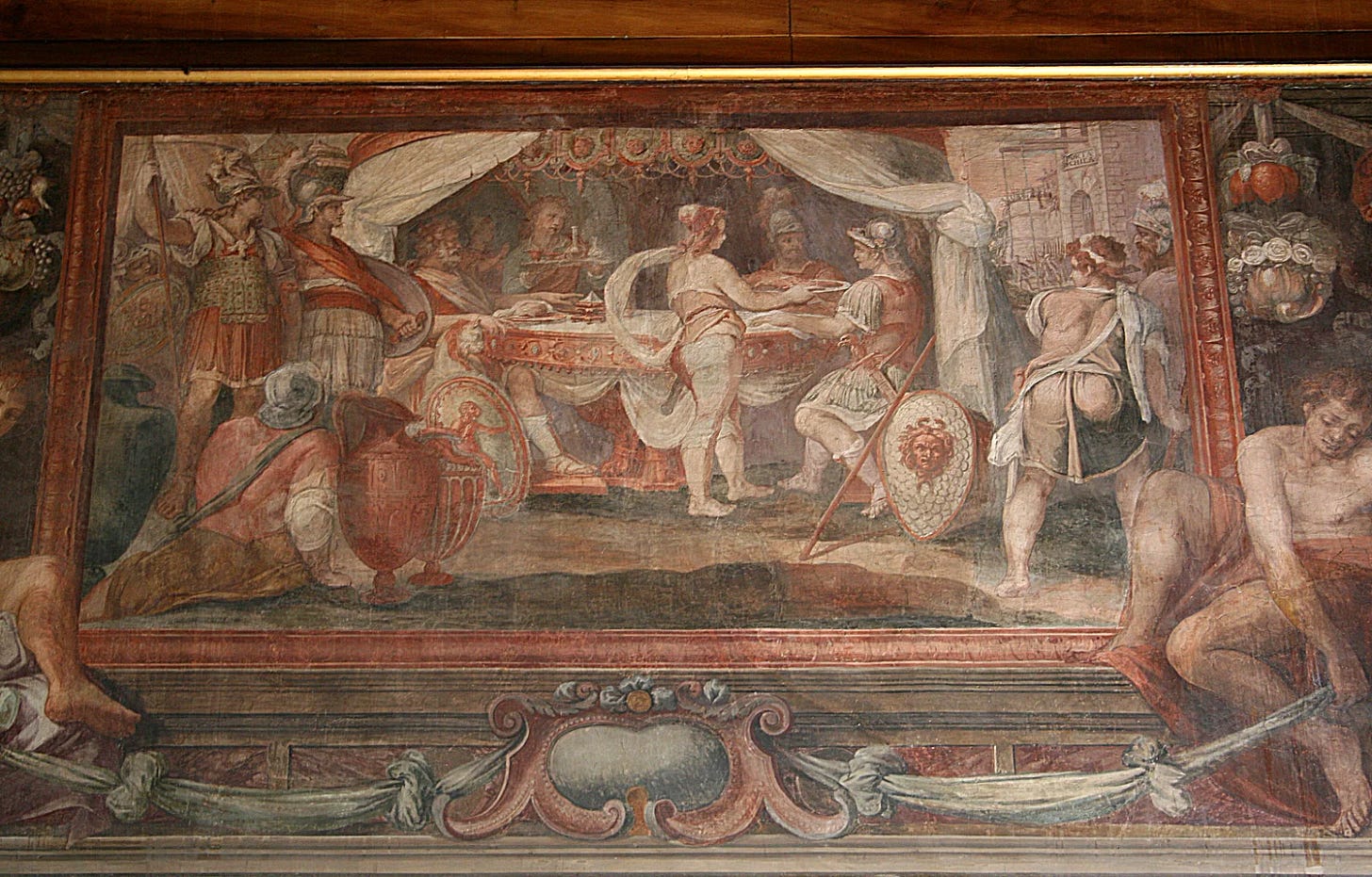

Thyestes

Thyestes is one of Seneca’s most powerful plays, a bleak revenge fantasy and a study of evil. Like Seneca’s Medea, it’s based on one of Euripides’ plays and seeks to make the moral lessons of the story explicit.

The plot follows Prince Thyestes, who lives in poor but virtuous exile in the wilderness. He made mistakes in his youth but found peace after distancing himself from the corrupting temptations of the court. The story begins as King Atreus, his brother, tries to lure Thyestes back to Argos by promising him co-rule.

Thyestes is safe and free from moral compromise in his simple life, but his children urge him to accept his brother’s offer. The prince senses no good will come from returning to Argos, but he can’t say no to wealth and power.

This is an echo of Seneca’s life. The philosopher was exiled to a comfortable and safe — if not particularly exciting — life on Corsica by Emperor Claudius. Then, a tempting opportunity is dangled: He can become Nero’s tutor and move into the upper echelons of Roman power and influence.

Seneca wasn’t stupid. He knew what life at court was like; he went anyway.

Later, Seneca opaquely wrote,

“...some of us have not stood bravely enough by our good resolutions, and have lost our innocence, although unwillingly and after a struggle; nor have we only sinned, but to the very end of our lives we shall continue to sin.”

To me, this reads like Seneca explaining his own mistake and why Thyestes sought power, even though he suspected it would ruin him.

Seneca left his exile and got wrapped up in the machinations of Nero’s court. Thyestes leaves the wilderness and is lured into the clutches of Atreus, who’s been driven mad by his anger and lust for revenge (following their dark and complex family history).

Ultimately, Atreus murders Thyestes’ children and serves them to the prince at a banquet. Thyestes calls on Jupiter to avenge the wrong, but gods usually don’t save the day in Seneca’s work. Humans suffer the consequences of their mistakes.

There’s no resolution or higher purpose at the end of the story; readers are left feeling like the characters brought the madness upon themselves. The tragedy could have been avoided if they’d just learned to control themselves.

There are many passions at play in Thyestes, but anger stands out. Atreus has been driven mad by it. He can’t let bygones be bygones and yearns for revenge.

I imagine Seneca hoped his disenchanted audience would be repelled by Atreus and seek a cure for their own anger. He had “De Ira,” or “On Anger,” ready for them. It dissects Atreus’ problem and serves up the Stoic cure.

He’d probably suggest we use a millennia-old philosophic journaling technique to clarify our thinking and move toward Eudaimonia.

The Philosophical Trojan Horse

All of Seneca’s plays work this way: be tempted to watch the spectacle, observe the irrational madness of passion, and be driven into the consoling arms of philosophy. Each play is a philosophical Trojan horse.

The same effect is always at work in our lives. If you watch closely, you’ll see how passions destroy so much of what is good. Seneca is just cranking things up a notch to make the connection harder to overlook.

So perhaps in this regard Seneca isn’t so much a hypocrite as a clever philosopher. He couldn’t undo his mistakes, but his lessons might save us before it’s too late.

About the Author: Andrew stumbled on Meditations at age sixteen, and Marcus Aurelius and Socrates took up residence in the back of his brain soon after. He's a former journalist interested in ancient history, philosophy, nutrition, and partner acrobatics. He writes about applying practical philosophy to modern life at Socratic State of Mind.