A man works hard, creates a business, and retires with $2.7 million and a stream of passive income by age forty. Hasn’t he done enough?

At least as far as the man’s wife is concerned, the answer is no: she grew disgusted with his “retirement.”

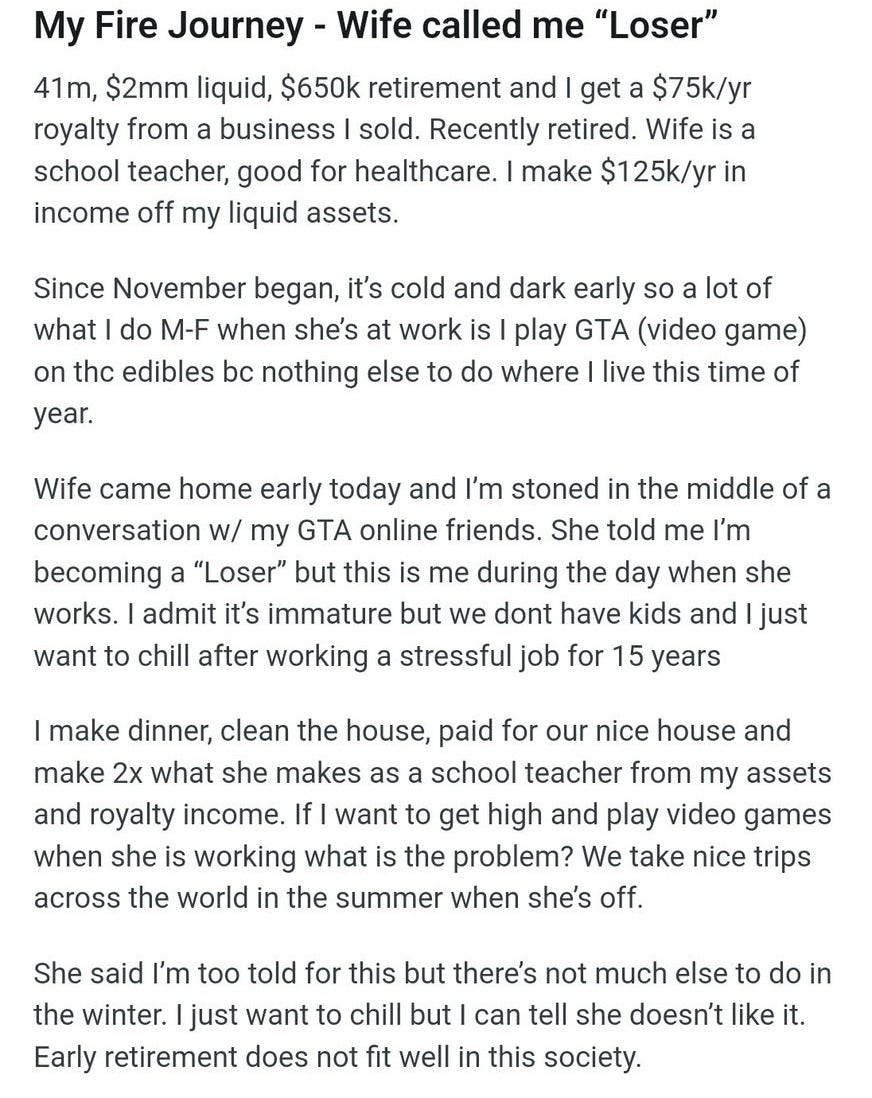

His story recently went viral on Reddit and X:

The responses ranged between mockery and commiseration. For some, the fact that this man was a “loser” was obvious.

Video games and pot for months on end? Come on man. That’s sad.

Others simply couldn’t fathom why edibles and Grand Theft Auto weren’t reasonable pursuits for the financially independent.

Isn’t it the paradise we all seek? You need to fill that free time with something, right?

Cue The Romans

“Otium, catulle, tibi molestum est.”

(Idleness, Catullus, is destructive to you.)

— Gaius Valerius Catullus, Poem 51

Most humans have worked till they died. The lucky had competent children to take some of the burden as they declined, but few could give up work entirely. Even if they wanted to, the next generation needed them.

Which is why the writing of Greece and Rome’s tiny elite are a sneak peek at what the modern world is dealing with. Although people complain about our modern world, a society where many spend 10-30 years not earning money shows a staggering level of affluence by historical standards. That the Financial Independence Retire Early Community (FIRE) regularly retires in their 30s and 40s is even more unprecedented. Antiquity had nothing on this scale.

But two thousand years ago the Roman elite experienced the same problems our retirees do. We can learn a lot from how they wrestled with leisure, work, and meaning.

Otium Is Life

The Roman aristocrat and poet Catullus was rich enough to do nothing, but understood it degraded him. He explores this in poem 51:

“Idleness, Catullus, is destructive to you.

In idleness you revel and delight too much

Idleness has destroyed both kings and

blessed cities before.”

The Latin word I’ve translated as “idleness” is “otium,” perhaps the most Latin word ever.

Otium is an entire way of life which the Roman elite sought, idealized, and also dreaded. It was the opposite of “negotium”, a way of life synonymous with wheeling and dealing and being in the mix.

Otium: Rest at your villa or city manse. Enjoy an endless stream of banquets and sex, or dive into philosophy, art, and learning.

Negotium: Fund charitable programs and public works with your massive hoard to increase your family’s renown, serve as provincial governor, build a fleet of merchant ships, craft laws in the senate, and defend clients in court to win rhetorical prestige.

Some Romans were so caught up in the dopamine joyride of negotium that they got stuck. They worked like dogs till they died, though they possessed enough assets to take it easy.

They never obeyed Socrates’s famous dictum: know thyself.

They couldn’t slow down long enough to begin.

The Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote an essay called, “On the Shortness of Life,” a critical piece of the Stoic canon everyone should read. Seneca argues that people waste their lives caught up in utilitarian-seeming bullshit and need to make time for deeper, more meaningful pursuits. They need otium. Unfortunately, otium often doesn’t go well, as Catalus attested.

Modern slaves are in the same boat as philosophy-bereft Romans. They’re pathetically chained to bullshit. They can’t resist Instagram and doomscrolling in their few hours of free time, and you think they’ll thrive with unlimited leisure?

Leisure will break them. It will reveal how shallow their lives are, and how bereft of meaning.

Cattalus gorged at late-night banquets, drank himself senseless, and got it on with Roman matrons. Is the FIRE guy drowning in pot and GTA that different?

Beyond Otium:

Rome’s most Otiarius man might be Seneca himself. We don’t know precisely what he did to piss off the emperor Claudius, but he was exiled to Corsica in 41 AD and spent eight years in unsought otium. He had wealth, leisure, and free reign of the island’s beautiful nature and limited cultural life, but struggled to come to terms with not being a mover and shaker anymore. But he didn’t fall into self-loathing, drink, and degeneracy, as many otium dabblers did.

Perhaps hinting at a near miss, he later wrote:

“Leisure without (study/reading) is death, and the burial of a living man.”

— Seneca, Letter 82

Slowly, through his philosophical thought and literary output, he found a way to peace. Perhaps he couldn’t contribute how he preferred (and later attempted, unsuccessfully, to tutor the young emperor Nero), but both by improving himself and the minds of those living abroad with his writing, he found contentment.

He wrote:

“Just as a person who is responsible for his own moral deterioration harms not just himself but all those whom he could have benefited had he improved himself, so whoever serves himself well benefits others by the very fact that he provides what will be helpful to them.”— Seneca, De Otium (On Leisure), 3.5

The reason FIRE guy is pathetic, by Seneca’s measure, is that he’s an able man. Any entrepreneur who retires by forty can probably accomplish most of what he sets his mind to. That the best use he can imagine for his mind is pot and video games is simply sad.

But even for people of limited ability, rotting on the couch means letting the world down. The world needs what only you can give it, even if that means making sure an elderly neighbor has someone to talk to or coaching a youth basketball team.

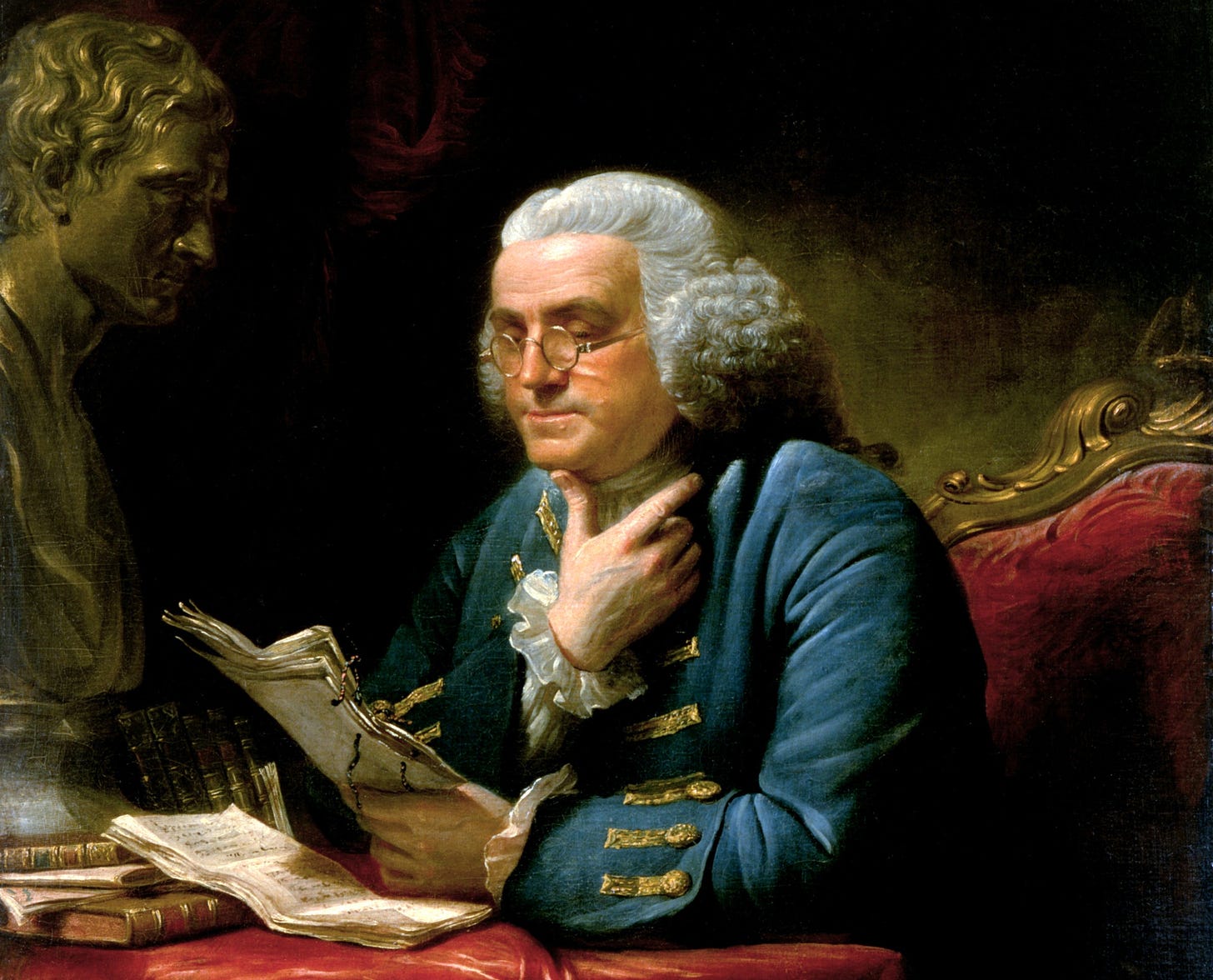

Ben Franklin: The Ultimate Otiarius

We think of Ben Franklin as a productive man of negotium. He was a successful printer who developed franchises throughout the colonies. He wrote bestsellers and became a successful newspaper publisher.

But he’s really the ultimate man of otium. Franklin was FIRE before anyone knew what FIRE was, building a nest egg that allowed him to retire at the age of 42, much like our modern FIRE man.

But Franklin’s otium accomplishments put his modern counterpart to shame.

They include:

Convincing France to send America money, soldiers, and a huge fleet that helped the colonies win independence.

Contributing to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitutional Convention.

Establishing The first public library and hospital in America and the first public fire department in Philadelphia.

Fighting to abolish slavery and serving as president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society.

Founding the University of Pennsylvania

Experimenting to prove lightning was just electricity.

Developing the lightning rods that have prevented tens of thousands of infernos.

And the list goes on. Franklin knew how to put otium to use like nobody else, and it’s hard to find a better record of public service and virtue in retirement. I’d characterize him as dragging what appears to be negotium into otium. He subverted negotium by injecting virtue. Gone were the money-making schemes, and if they increased his renown, it doesn’t appear to have been the goal.

His life was hardly devoid of pleasure. He famously carried on affairs, ate well, and enjoyed socializing and popular culture.

But at the end of the day he saw his role as contributing to the public good, and he never let America down.

Modern FIRE man might have half the talent of old Ben. Hell, I’m probably not 1/10th as talented, and most of humanity is in the same boat.

But if we each use an increasing sliver of our limited otium virtuously instead of devoting it entirely to idleness and pleasure, the very bedrock of society might shake.

And if you’re a slave like FIRE bro? If you can’t pry yourself away from shallow pleasures long enough to know yourself and make a contribution?

It’s time to find yourself a mast:

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you enjoyed this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

I think it's useful to distinguish between a job and your work. Your job is whatever gives you an income. Your work is the thing which you feel makes the best use of your creative and productive powers, and towards which you feel a sense of duty. A hobby, by the way, is like work something which you feel makes the best use of your creative and productive powers - but towards which you feel no sense of duty.

If you are lucky and/or have organised your life well, then your job and work are the same. But they needn't be so. For example, there's many a man who does a job like rubbish collecting, so he can support his work of being a husband and father.

For a roof over your head, you need a job. To keep your body, mind and soul healthy you need work - and a hobby.

If you're not sure whether it's a job or work, simply note whether you're checking the clock to see if it's time to stop or if it's time to start. Nobody loses themselves in their job, but people frequently lose themselves in their work.

If playing GTA all day makes the best use of your creative and productive powers, then I would suggest you need to develop your creative and productive powers to a higher level - it's less creative and productive than a rubbish collector, who at least helps keep the streets clean of filth and thus prettier than they would be without him. And if you feel a sense of duty towards GTA, you have problems, I'd say.

So the man used to illustrate this story had neither work nor hobby. He was just passing time. We all do that occasionally, but he made it a lifestyle. People are instinctively disgusted by people without work or hobbies, even if they can't articulate why. That's also why we dislike "hustle culture" guys - they demand we treat a job like work.

This brings up something I've been thinking a lot about lately (and that I hope to write about soon): the incompatibility of optimization and values as modes of deciding.

FIRE guy is doing the "optimal" thing. In the *game* he was playing, he scored as many points as possible (money) and now he has abundance (time). But because optimization relies so heavily on quantification, it must consider any hour spent or dollar gained as good as another. It can't distinguish between an hour of volunteering and an hour of day trading, an hour with your grandkids and an hour of GTA, a dollar spent on groceries and a dollar spent on a bigger boat. I actually think most people, if asked, could draw a pretty compelling picture of the good life, but when they make choices in reality, they optimize themselves out of virtue.