The Oracle in Our Books

Breaking our chains, one unexpected thought at a time.

We’re locked in.

Our habitual thoughts wear on the brain like wheels on a dirt road, creating hard-to-escape ruts we might feel doomed to follow. Sometimes we’re stuck traversing these rutted tracks year after year, and when emergencies or uncertainties arise, we’re ill-equipped to escape them and find solutions.

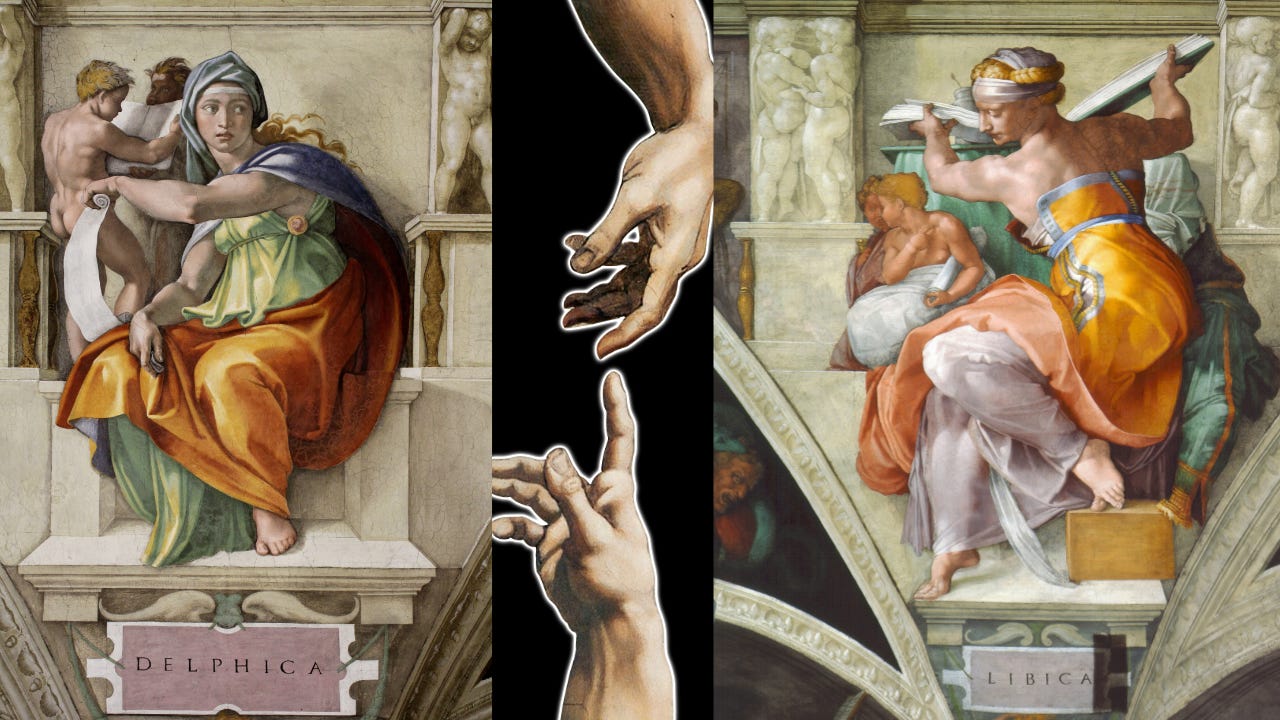

The feeling is ancient, and our progenitors created a variety of solutions. When beset by personal or geopolitical troubles that seemed inescapable with their normal cognitive toolboxes, the ancient Greeks and Romans resorted the oracles at Delphi and Ammon and the Sibyls of Ionia and Cumaea.

They sought blasts of divine wisdom to open new vistas of understanding and possibility; what they received were terse, enigmatic missives they had to wrestle with. They struggled to interpret and apply them in the real world. It was in this struggle that the messages bore fruit.

Socrates thought he knew nothing, but the Apollonian Oracle at Delphi assured him no man was wiser. Reconciling those two ideas would form his approach to philosophy and life. When a massive Persian army marched on Athens in 490 B.C., the Oracle told the Athenians, “A wooden wall alone shall save you, a boon to you and your children.”

But Athens’ circuit walls were made of stone, and the ancient wooden palisade around the Acropolis was in ruins. What could the Athenians possibly make of this “solution?” They wracked their brains.

Then Themistocles arose in the assembly and insisted the “wooden wall,” had to be the collective hulls of Athens’ navy. He convinced his people to abandon their homeland and flee over the Wine-Dark Sea. Victory, the oracle seemed to say, could only be won on the waves. This abandonment of Athens would have been unthinkable without the “permission” of the oracle to consider it, and yet now it was permissible.

The Persians razed Athens, but the populace was unharmed on Salamis. Ultimately, the outnumbered Greek fleet — formed around a core of Athenian triremes — crushed the Persian navy at Salamis. The logistically-isolated Persian army was left to contend with thousands of motivated Greek hoplites, who routed them soon after. The “unthinkable” turned out to be the best course.

There’s no friendly neighborhood oracle to consult these days, but we don’t need riddling seers to get the same effect.

The Chinese have long consulted the I-Ching divination text. Its words mean little in isolation, but gain meaning via the struggles people bring to them. Users think of a question and roll dice or coins to figure out what message to turn to (there are 4096 possible combinatory messages). Upon reflection, they often find the message contains an insight they wouldn’t have considered otherwise.

The Romans did something similar by consulting the Sibylline Books kept in a sealed stone crypt on the Capitoline Hill.

The point isn’t playing with magic or seeking the divine, but getting ourselves to look at life differently and question our assumptions. Often, these insights are enough to escape a rut or “unsolvable problem.”

Conversations with wise people holding dramatically different perspectives can cause similar reorienting eureka moments. But we might lack friends holding different perspectives; we tend to insulate ourselves in human idea bubbles, and even beloved friends may not be wise in a helpful ways.

Luckily, we have great books full of wise perspectives that are often alien to today’s norms and assumptions. Each can be an oracle.

My original exposure to his idea came with the I-Ching. I’d been single for a while because I’d met no one worth dating. Then a woman expressed clear interest in me, angling for a date, and I started to wonder — am I being too picky?

She was attractive and nice, but I knew in my gut she had no long-term potential, and that it was best to not get involved. But she persisted and I began to doubt my instincts. Why not have one of those “flings,” that always struck me as unwise and problematic on so many fronts? And who knows, maybe I was wrong.

Feeling stuck, I flipped some coins and consulted the I-Ching. It told me — in its cryptic way — what I already knew in my gut; I’d never abandon someone who’d put their trust in me because a better option came along. That’s not how I operate, and anathema to my morals. So beginning that process was tantamount to locking myself into a relationship that was at least a significant opportunity cost, and probably doomed to fail for lack of compatibility.

Having my situation reframed along these lines cleared the air, and all doubt vanished; I turned away from the relationship and into other things. Yet into this fallow space arrived my girlfriend. She’s clearly a great match for me, and I pursued her without hesitation or doubt. Had I not taken in the perspective of “the oracle in the book,” I might have made a perhaps life-altering mistake (but who knows?), closing myself off to a great person and all that’s followed.

Similar uncertainties arise in my life several times a year. My habitual perspective yields no clear answers — I need to be shaken out of my rut.

I don’t consult the I-Ching these days, but find my philosophy practice can do a better job.

I wrote about the philosophic “idea-a-day” book format recently, and almost all these can become useful oracles.

The goal is discovering a striking idea — a sententiae — stripped of its context so it’s almost universally applicable.

I was reminded of this today when working on a long-term translation project. I’ve been putting aside short Senecan sententiae shorn of their original context in a notebook for several years, and today decided to translate this one:

“I was shipwrecked before I boarded the ship.”

"Naufragium, antequam navem adscenderem, feci.”

— Seneca, Letters, 87

Since I’d forgotten the original letter’s main idea, I assumed the sententiae described a psychological pre-defeat taking hold before a challenge is even at hand, dooming what’s to come. Dispirited armies do not conquer, despairing athletes win no medals. That sort of thing. I can think of several times in my life where the presumption of doom defeated me before any rival or obstacle heaved into view. I was preparing an illuminatory spiel on this theme in my head as I worked out the translation.

Then, I cracked open the original letter to find that Seneca meant something entirely different. Indeed, the editor of my Latin text put in a footnote explaining that this phrase describes a person setting out on a journey with little or no baggage (as if he’d been shipwrecked and lost everything). It praises minimalism and having enough to meet your needs with nothing in excess.

And that makes sense too. I’ve spent years of my life abroad, and hauling baggage from country to country is a pain that taught me the joys of limiting myself to enough. But I bet there are multiple other worthwhile interpretations that people of different situations could bring to this very short idea.

Are any of these ideas less valid than Seneca’s original? I’d argue no, they’re all useful perspectives if they’re what you need to hear. Your concerns determine which one rises to salience.

So how do you use a book like an oracle? Simply flip to any page in the books I mentioned. Read the smallest sensible unit of text — a sentence or a paragraph — without reading the context below. If you stay with the idea for 3-5 minutes, perhaps journaling on it like a philosopher, you might be surprised to find valuable insight into your situation. Feel free to flip to another idea if the one you found seems unapplicable after giving it some thought.

It’s not Magic. It’s not divine. It’s just a blast of random perspective that might be just what you need to get free of your rut and see clearly again.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

This is an interesting approach. I’ve heard of people doing this sort of thing, but never really thought it had much value. Using it as a tool to break out of conventional thought is compelling, though!

This is very similar to how the Book Ender's Game provided me the idea of "The Enemy's Gate is Down" which I've embraced as an intentional reframing to see if I change perspective, whether my problem changes definition. If it does, I didn't understand the problem properly.