The congressman couldn’t answer my question. That was a first.

By 2010 I’d been talking to him as a newspaper reporter for three years, and he’d always had smooth explanations ready for each setback. Glib, vaguely inspiring remarks rolled off his tongue. There was always a villain to blame or another obstacle to overcome in his quest for a more perfect union.

But that day — off the record — I asked why the law he’d introduced and passed with much fanfare two years before hadn’t moved the needle on the problem it addressed.

He frowned into the middle distance for a few moments. “Ya…,” he said. “Sometimes it does feel like the wheel isn’t attached to the rudder anymore.”

He moved on quickly, as if embarrassed to admit that while vested with more power than all but a handful of people in the United States, his efforts to effect positive change were often countered by a more powerful push in the opposite direction.

I’ve never forgotten his analogy of the wheel disconnected from the rudder, and looking around the world, I feel like it explains more problems than we might imagine.

You’ll Hardly Feel This Rape

The laws of economics and human psychology sometimes pool into inescapable quagmires. Once you recognize the resulting sludge, you’ll spot it at the root of many intractable problems.

Many have this at their core: their existence benefits a few people a lot and harms many people very little. “Concentrated Benefits, Dispersed Costs.”

Maybe we judge systems working this way as net goods worthy of whatever harm they cause. But some need reform or elimination, and the people who try quickly realize something — it’s virtually impossible.

The few people profiting from these systems expend lots of time and resources to safeguard their advantage. They hire lobbyists and donate to sympathetic political campaigns, pulling every string they can find. The cost of failure for each beneficiary is very high.

Lamely standing in opposition is the entire rest of the nation or local community. I say “lamely” because they individually stand to lose so little they usually can’t be bothered to protest at all. Perpetuation of the system costs a pittance, so they roll over and take it.

For instance, when the owners of the lucrative 49ers sports franchise wanted Santa Clara to help bankroll their new stadium in 2010 — though they didn’t need the money — they paid an inflation-adjusted $5.8 million to blanket the city in lawn signs, TV ads, and radio spots. The subsidy opponents raised a paltry $30,000. Unsurprisingly, the 49ers won and got their subsidy.

Examples of this dynamic are legion:

Federal home insurance subsidies for disaster-prone areas: Taxpayers shelled out $33 billion over the last decade. Affected homeowners and municipalities love subsidies, but they leave the nation exposed to shocks and incentivize fragile buildings in risky places.

NIMBY zoning restrictions: Minorities of vocal homeowners skyrocket their property values and preserve neighborhood character by resisting development. Many potential new residents face higher costs, long commutes, and the city is stuck with a stagnant tax base.

Mandated public consultations: A tiny minority of opinionated, often wealthy, mostly retired people arrive to berate public officials and scuttle attempts to bring very popular projects to fruition.

Most of my readers live in abundant countries, so one or a dozen of these “programs” isn’t a big deal. But in the United States and elsewhere we’ve accreted them for a century, and they’re collectively dragging the nation down. Society is less dynamic, equitable, responsive, and abundant because of them. In many cases, they’re accelerating wealth accrual by the already wealthy.

Take farm subsidies, which cost US taxpayers $30 billion a year and which economists think create little benefit and significant harm. Sixty percent of subsidies go to the largest 10 percent of farms — wealthy corporations and individuals who don’t need subsidies. But even average farmers are far from poor. In 2023, the median income from farming was $167,550 for commercial family farms, and their median total household income was $253,496.

Why Now:

“…the People who once upon a time handed out military command, high civil office, legions — everything, now restrain themselves and anxiously hope for just two things: bread and circuses.” — Juvenal, Satires, 10.77

The US is almost 250 years old, so why didn’t these problems plague us before? Were our ancestors more honorable or incapable of managing unfair redistribution schemes?

No on both counts. Our ancestors were as flawed as us on the whole, and these systems were rigged up in many ancient civilizations. Ancient Rome’s “bread and circus” strategy fits the bill.

Take taxes and food from the provinces.

Stage elaborate entertainments and distribute food in Rome to keep citizens from complaining about limited economic opportunities and influence erosion.

The “winners” were theoretically the capital’s citizens, but were in reality an even tinier group — the emperor, rich landowners, and the neutered senators who kept their grip on wealth and influence by buying off the populace.

So why is the United States — and wealthy democracies — suddenly burdened by these schemes?

Past federal, state, and municipal officials were sometimes corrupt or suborned by special interests, and often handed out crony contracts. But this barely mattered because government taxation and spending absorbed a minuscule piece of the pie. Officials misused money, but had much less of it to spend.

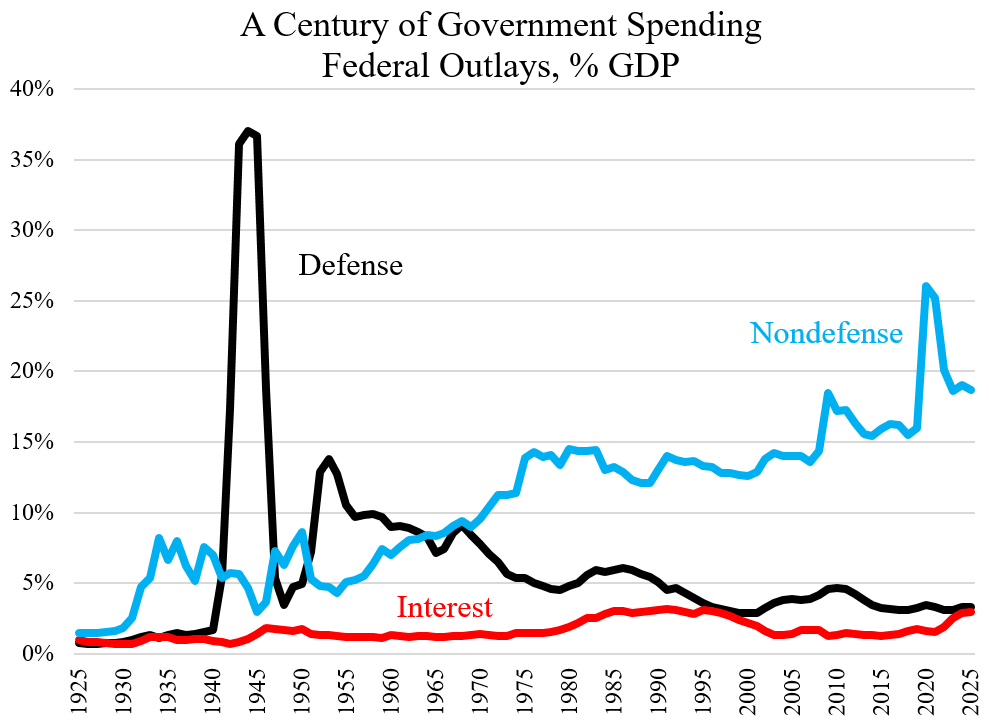

In 1925, US government spending amounted to 7% of gross domestic product. Now it eats up 50%, affording many opportunities to concentrate rewards and punish the population in tiny, barely-noticeable increments. Individually they don’t matter, but collectively they’re ruinous.

A Forest of Nos

No redistribution of public money is necessary; a few rules can affect the same result — a few benefit, the majority suffer.

There was no official tally of government regulations in 1925, but by 1936 there were about 3,000 pages of regulations on the books. By 2022 there were a staggering 188,000 pages regulating public and private life, an endless forest of nos citizens wander through.

Many regulations are helpful. They protect our environment and our health. But they often reward entrenched minorities at the expense of everyone else.

Why do Florida and Nevada require interior designers to be licensed and registered to design public/commercial interiors? Who’s harmed by poor aesthetics?

What malicious acts are Louisiana’s flower arrangers up to that require them to buy permits?

Twelve states require 200-500 hours of training and licensing to braid hair. Why? Who’s being hurt?

Even licensed dentists, who would seem to require heightened regulation, don’t perform better than unlicensed ones.

Across 175 countries, each additional step required before opening a business (education, tests, licensing) correlates to an additional 1.59% of national income going to the top 10% of earners.

The minority who can jump through the hoops wins. They’re incentivized to lobby for more hoops or keep the unnecessary ones in place to maintain their chokehold on the market. Everyone else pays more and gets locked out of the industry.

Pushing Back:

It will surprise no one that this inescapable quagmire, this counterforce keeping us stuck is….well…usually inescapable.

But there are a handful of examples where countries overcame entrenched interests and pulled free of the mire in a way that seems unlikely today.

New Zealand’s deregulation and desubsidization of its agriculture industry — from 1984–1990 — was an impressive win, taking advantage of a long fiscal crisis and public calls for economic fairness.

The greatest American example is the 1978 deregulation of the airline industry, which dethroned highly profitable entrenched players and made an entire transportation system affordable for the masses.

How did this happen?

Respected economists had been establishing the theory side of the “fix” for almost a decade.

US citizens were pissed, harried by soaring inflation and economic stagnation. They pushed politicians to do something.

Economist Alfred Kahn got appointed to the Civil Aeronautics Board and began stripping it of power from the inside.

Two powerful people — Ted Kennedy in the Senate and President Carter in the white house got behind the issue and pushed.

It was a perfect intersection of opportunity and powerful people willing to put some skin in the game and take risks. We don’t see that very often.

The Odds of Reform

If more reforms sound unlikely to you in the near future, we agree. I suspect that short of a major economic collapse or political or social upheaval, there are too few politicians with the intellectual heft, power, and willingness to take risks that would be required to see reforms through.

To see wider reform without upheaval I suspect we’d have to readopt a long-abandoned standard that’s disappeared from the public realm.

And that’s what I’ll be talking about in my article next week.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

Very interesting, I had always thought that it was the US government's defense spending which was ballooning out of control and was the primary driver behind government debt, but it's actually non-defense spending!? I am curious where those spending figures came from I would like to investigate that more.

Also I think this again points to a fundamental flaw in democracy itself, you write that "[special interests] hire lobbyists and donate to sympathetic political campaigns, pulling every string they can find." That there is the fundamental problem, if you have money, you can buy influence in a democratic government, and more money means more influence, more power to shape policy. We imagine the people in charge of a democracy or republic are the ones we elect, but as that Senator aptly stated, "sometimes it feels like the rudder is disconected from the wheel.

The true owners of a democracy are the people who can shape narratives through control over mass media by either having a stake in media companies themselves, or having the money to purchase space in that media to propagandize the population. Money can be directly translated into votes, its as simple as that, thus the rich and powerful will almost always control democracies.

Death by a thousand paper cuts. It's painful and slow but we accept it.