What People Get Wrong About Happiness During Hardship

Happiness on the rack gets a second hearing.

I was reading Cicero twenty years ago thinking, this is bullshit.

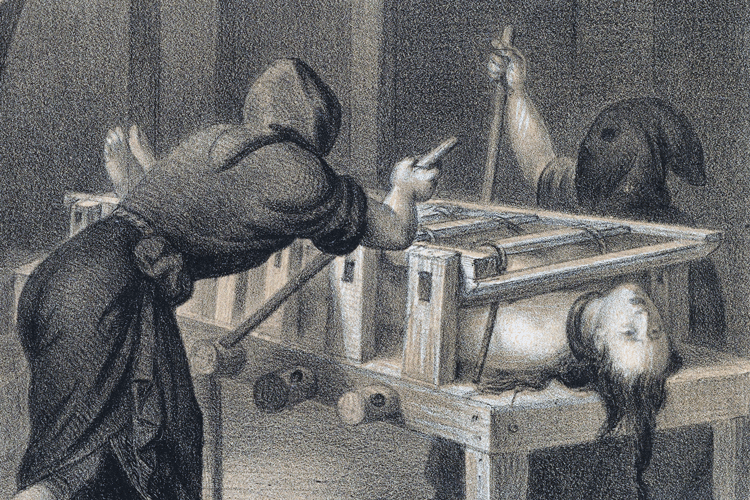

The book was Tusculan Disputations, and Cicero presented a Stoic argument that sages — i.e. incredibly accomplished philosophers — would be happy while being tortured on the rack.

It’s presented as something to aspire toward, but I couldn’t swallow it even as an ideal…which says something. If anyone was primed to accept Stoic dogma, it was me. I’d begun using Stoic techniques harnessing disdain and decomposition to rid myself of unreasonable desires. I’d found I could reanchor and use several types of gratitude to make myself happier. I’d begun to mutter my mantra.

But this was too much. It’s one thing to use philosophy to become more resilient, but I doubted even a sage would be happy as pliers ripped off their fingernails and hot irons branded their skin.

I tossed the book aside, but it was only a few months later that I began to reconsider.

Man On The Rack

Philosophy spells out the truth, but fiction embodies it.

This was the case when I opened Shantaram not long after giving up on Tusculan Disputations.

The first paragraph reads:

“It took me a long time and most of the world to learn what I know about love and fate and the choices we make, but the heart of it came to me in an instant, while I was chained to a wall and being tortured. I realised, somehow, through the screaming of my mind, that even in that shackled, bloody helplessness, I was still free: free to hate the men who were torturing me, or to forgive them. It doesn’t sound like much, I know. But in the flinch and bite of the chain, when it’s all you’ve got, that freedom is an universe of possibility. And the choice you make between hating and forgiving, can become the story of your life.”

That’s not happiness. Not how I’d been thinking about it. But it hinted at equanimity and meaning to be found amid pain, a freedom achievable on the rack, after the loss of a loved one, or during any painful time.

It took me years — while battling a painful autoimmune disease — to realize one of philosophy’s chief treasures is subversion. It can pry meaning free of physical reality like a crowbar and bestow it where we wish.

Philosophy can’t negate physical sensations, of course. Nerves fire when the skin is lashed. If the Spanish Inquisition tears me apart, I’ll probably scream.

But philosophy can transform our experience like alchemists transforming base metals into gold. Yes, that knife still hurts. Yes, we’d prefer to not be cut. But if the wound has meaning, if it allows us to be better, we can alchemize the whole thing in a direction our tormentors weren’t expecting, or desiring. The knife can make us better, stronger, more ourselves.

A Return To Cicero:

Years later I returned to Cicero to give him a second hearing. It turns out I was too harsh, and Cicero might be a victim of questionable translation choices (as many ancient philosophers are).

Cicero uses the Latin word "beatus" to describe the wise man's state during torture, which my edition translated as “happy.” That would have been reasonable for Latin literature written before Cicero’s time.

But Cicero was involved in a project to give beautus a new technical philosophical meaning and equivalency to the Greek word "eudaimōn." It’s related to happiness in that it’s a positive state similar to high self-regard, and moral flourishing, but it’s not a feeling of pleasure or bliss.

Cicero insists that the sage can maintain their virtue and inner tranquility (ataraxia) even under torture. They suffer like anyone, but maintain rational judgment and moral character, and can subvert experiences in that end.

Stoicism is demanding, but it never demands we become superhuman sages in order to practice it. Every human can begin to subvert, reframe, and find tranquility among trying circumstances.

Concentration camp survivor Viktor Frankl, who experienced more than his fair share of pain and abuse, put it best:

“Forces beyond your control can take away everything you possess except one thing, your freedom to choose how you will respond to the situation. You cannot control what happens to you in life, but you can always control what you will feel and do about what happens to you.”

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

I'm finding that a lot of my understanding of Stoic philosophy is influenced by translations of words and their subtly different meanings. It is very difficult to navigate. Thanks for pointing this one out!

As Hadot would say, philosophy provides you with the tools to circumscribe the present and find infinity. In that infinity you can find attitudes to shape your present.