There are upsides and downsides to jettisoning religion.

The upside: Removing labels and firm beliefs from our identity makes us less stupid. Cognitive dissonance strikes when probing subjects grafted to our identity, so it’s painful and we’re reluctant to do it. Religions usually demand we attach giant “believer” labels to ourselves and endorse particular dogmas. All our thinking must tiptoe around those parts of our identity to avoid discomfort — a recipe for stupidity

The downside: Many who jettison religion find themselves adrift without a compass or decision-making playbook. Today they’re under the sway of one guru, tomorrow, a tiktoker or YouTuber wins them over to another cause. Because nothing is forbidden, everything is possible, and many drown or stagnate in possibility. Nihilism, pleasure, and escapism have no counterweight. Impulsivity can always be justified. Many who jettison religion find themselves unsatisfied with total freedom.

Spirituality As Shitty Religious Non-Alternative

People are jettisoning religion in increasing numbers, but many claim something interesting: “I'm Not Religious, I'm Just Spiritual," as if a substitution was occurring.

What is this spirituality people pursue instead of religion?

When I press the spiritual crowd, their definitions are often nebulous. I suspect most don’t have solid ones.

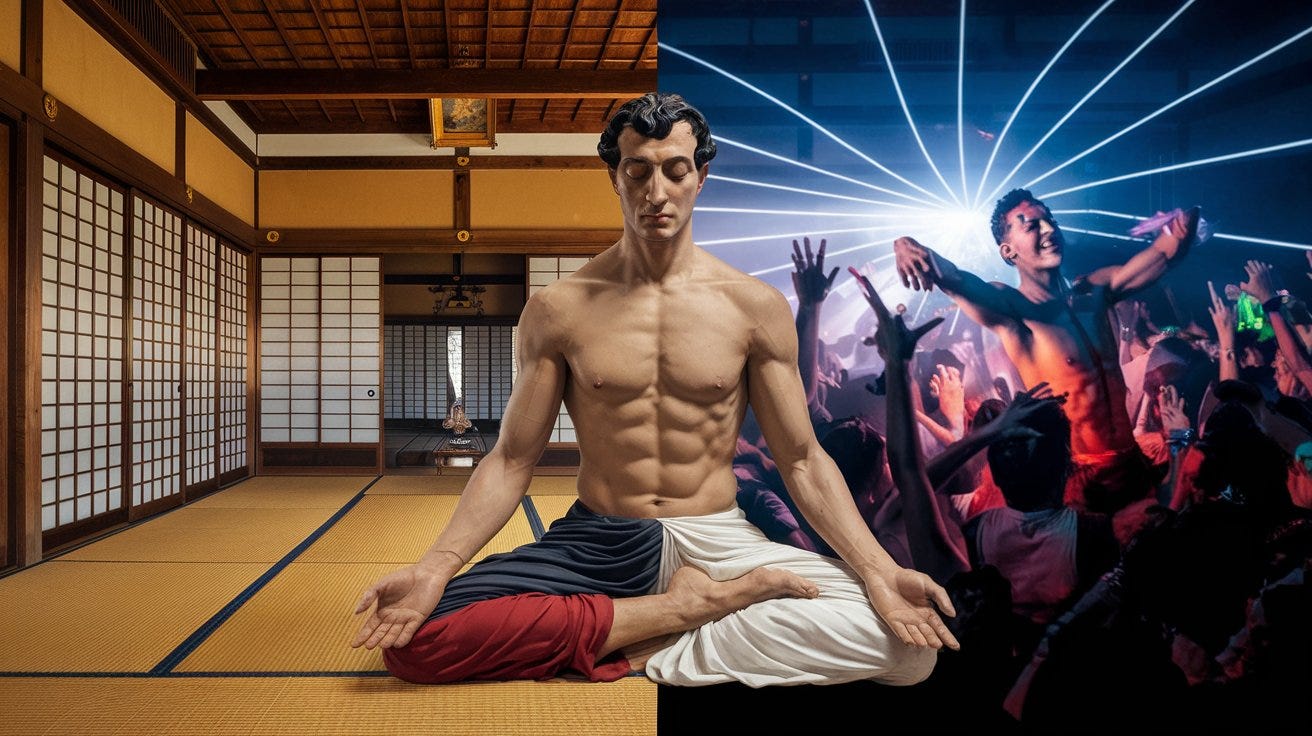

Spirituality probably isn’t an alternative so much as something occasionally intertwined with religion. It’s an experience — a state or feeling we can achieve. It might knock during dance, meditation, flow states, or while chanting prayers and mantras. I’ve had many friends find spirituality in drugs.

Spiritual experiences are great. They might pull us from a rut when we’re floundering or provide revelations. I’ve had several such experiences and cherish them all.

But while spirituality may be necessary for a good life, it isn’t sufficient. Spiritual experiences always end and then we’re left living our actual lives. That’s one reason many spiritual seekers are miserable. They carry little from their momentary ecstasies into their mundane moments.

The Lost Humans of Austin

I live in Austin, Texas, which was the US weirdness hotspot twenty years ago (the city has become more conventional during my time here). But Austin’s weirdness is just the Western zeitgeist writ large, dialing to 11 our prohibition-shedding urge.

I’ve befriended Austin’s dharma bums, drug-tripping psychonauts, polyamorous peeps, and other refugees from normal American life. Many identify as spiritual but not religious.

A small handful live good lives and find happiness, but most are erratic wrecks. They continuously make bad financial, relational, and career decisions that would have baffled their grandparents equipped with a “non-weird,” compass.

I’ve often asked myself what separates the 20% who thrive in their weirdness from the 80% who don’t. It seems to me that the 20% cling to dogmas all their own, sometimes hermetically questing after particular brands of weirdness with intentionality and concrete principles. Many have a regular “practice,” but also a decision-making framework that clarifies and limits optionality.

So the 20% are “spiritual,” and weird while practicing limiting religions all their own.

Come and Get Your Handcuffs

There’s a truism among artists — the more constrained you are, the more creative and productive you become. Yet artists are rarely excited about imposed creative constraints.

Humans feel the same about their lives. Even those who admit guardrails contribute to their well-being sometimes feel stifled by them. No one wants constraint. We want to be free!

But who’s more free, the person who avoids the minefield because they’ve got a map, or the one who blows themselves up prancing across in pursuit of spiritual adventure?

The real question: what handcuffs will serve you best? The sirens are always singing on the rocks. Will you plug your ears so you hear nothing? If you want to listen to their rapturous song without self-destructing, what mast will you tie yourself to?

There’s a great deal of freedom in choosing a mast. We don’t need to stay inside the boxes provided by popular world religions. So what does crafting a mast look like?

Painting a Religion

Like art, religions attempt to construct meaning in the face of a tumultuous and often painful reality. We’re meaning-seeking creatures and often fall into despair without it.

Religious meaning becomes accessible when we put aside self-preoccupation, “vice”, and our urge to draw attention to our unique and special qualities to embrace an expanded perspective. Part of this is limiting optionality, and there are infinite ways to do it.

Worthwhile religions have commonalities:

Religions limit our ability to do some enjoyable things. We need to be willing to suffer for our religion, and part of that is abstinence.

Our religion must guide us. Instructions for spiritual experiences aren’t enough. Religions need practical and prescriptive instructions for everyday living.

Our religion must provide an expanded perspective in which choices have significance beyond our minds, whether on a humanity-wide, earth-wide, or cosmic scale. Good religions invest lives with resonant meaning.

I’ve found binary rules don’t work, though they might for you.

What does work for me is the ritual of pushing back against and “testing” every thought and desire against the measuring stick of virtue — wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation. This is lifted directly from Stoicism.

I have some peripheral practices, but my restrictions all come back to this. I’ve talked myself into many unpleasant things, and out of many pleasant things, because, upon reflection, I realized that was the virtuous thing to do. But why should I care what’s virtuous?

Justifying Your Mast

Why tie yourself to a mast when you can be unbound? Even if the mast is good for you, you probably won’t embrace it if you can’t justify it. It will merely be a quixotic affection, an eccentricity. Nihilists can’t take masts seriously, so they drop them.

Some modern Stoics accept that virtue is good while believing the universe is unordered, meaningless, and mundane. But most people find this no more compelling than the vanilla humanism that’s circulated since the Renaissance. Humanism has few converts.

The “spiritual, not religious” crowd jettisons birth religions precisely because they can’t justify them. They thought those masts were full of contradictions, so they gave up on the idea of masts entirely.

So The ultimate question is, can you justify any sort of meaning-imparting cosmology that calls for your preferred mast? Dogmatic certainty isn’t necessary — it’s actually a cognitive liability. Traditional religions once valued practice more than dogmatic belief, as Karen Armstrong argues. What you do has always mattered most. That goes doubly for this project.

Perhaps you might adopt Stoic pantheism. You might use science to argue that something akin to virtue is at work in our universe. It’s up to you to find what doesn’t strike you as absurd, and what you can build your mast around.

The Straight and Narrow Path

Spirituality isn’t the problem. Weirdness is fine. What you can’t be is unmoored from a restrictive decision-making playbook inferred from something resonant.

You’ll meet few happy nihilists. I certainly wasn’t happy when I thought the world lacked meaning.

Now I see meaning all around me, and act like it’s there, and that makes all the difference.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

Great points. I've maintained that religion is more of a psychology than a theology. When people ditch the structure they're at the whim of turning anything into a religion, often without the beneficial outcomes.

Humans need the structure that religion provides. It's also aspirational which helps.

https://www.polymathicbeing.com/p/religion-as-a-psychology

This is a really interesting breakdown. Another benefit of organized religion you didn't mention is community. The "just spiritual" people rarely gather in community to the same degree as the members of a mosque/church/etc. Pagan community groups are usually smaller and much less stable. Maybe that's due to the individualized nature of the beliefs, as well as the obvious fact that there are fewer people to come together. It's harder to maintain a mast on your own than when you have a solid group of people backing up your beliefs.