They should have used kayaks.

When anthropologist Marcel Mauss asked the Athabascans of Alaska why they insisted on building rickety boats from moose skin and bark when the kayaks of the neighboring Inuit won every practical contest, they could offer only disdain as an explanation — they hated the Inuit. They wanted nothing to do with their kayaks.

This sort of reasoning peppers human history. We claim to make decisions based on utility, but often harm ourselves to score “moral points,” against outgroups.

Cultures are, effectively, structures of refusal. We build them as psychological moats against our neighbors as much as for any practical purpose. But in hiding behind moats, we sometimes get trapped.

Some of our greatest art, music, and architecture emerged from outward-focused self-definition, but so too have our most devastating conflicts.

So before firing another salvo in our polarized American culture war, it’s worth considering how incredibly predictable we’re being, and what happened to some of the other civilizations that followed this path.

“Societies live by borrowing from each other, but they define themselves rather by the refusal of borrowing than by its acceptance.” — Anthropologist Marcel Mauss

Our Predictable Human Pressure Cooker Cycle

I’ve observed:

We gain in-group unity at the expense of external conflict/tension by defining outsiders as ideological threats. This is the beginning of the “pressure cooker cycle.”

In the pressure cooker, we ideologically self-contort away from threatening outgroups to pursue purity, caricaturing ourselves. Anthropologists call this schismogenesis. Sometimes these caricatures benefit us, but they often embrittle societies by constraining options.

If outgroup enemies collapse, we do a “victory turn,” and soon choose an internal enemy to contort against (if we can’t find another serious external threat). This is rarely in our self-interest. Polarization and civil conflict result.

Much human misery stems from this sad cylce, and I’d like to explore just how shockingly common it is.

First we’ll examine oppositional self-caricature and a common victim of the victory turn before touring historical pressure cooker cycles.

Native America’s Self Caricature:

Have two neighbors ever been more different than the Yurok and the Kwakiutl1?

It’s hard to imagine a larger chasm existing between them during their 18th-century heydey on North America’s Pacific coast. It almost seems like they built their cultures in response to each other. Perhaps because they did.

Anthropologist Walter Goldschmidt said the Yurok’s glorification of work, disapproval of pleasure, food, and comforts, hoarding of money, and emphasis on simplicity and egalitarianism reminded him of the Puritans2 .

All property — houses, blankets, money, land — was privately owned. Money was needed to purchase everything important. This was an unusual system among Native Americans.

Upper-class Kwakiutl, on the other hand, disdained work as something for slaves and peasants, hoarded possessions past the point of utility, gorged on food, got fat, kept slaves, had their peasant craftspeople make incredible art, and regularly spent all their accumulated wealth on massive festivals.

How did this extreme polarization, separated only by California’s Klamath River, develop? Was it utility or cognitive bias that drove them apart?

Some readers will assume utility explains everything. They’ll look at it like an economist and assume both groups made rational choices. The Kwakiutl reliance on fish required lots of labor, so perhaps they sought slaves to do the labor, which drove slave raids, which led to hierarchy, etc. But I don’t think utility alone can explain these extreme differences.

People embrace post-facto justifications and probably believe them. Underlying psychological processes are opaque, and deciding where utility ends and cognitive bias begins is challenging. I suspect Yurok and the Kwakiutl polarization developed from a mix of both factors.

The arrival of Europeans interrupted their rivalry, so we don’t know how things would have played out. Perhaps they’d fight till one side dominated the other. Perhaps they’d find an equilibrium of competition and hatred that would endure centuries.

What we can say is that each group despised the traits of the other. If this was the lone example of extreme polarization among ideological rivals, we might overlook it as a quirk. But it’s not. More polarization than expected among rivals is more the rule than the exception. And history tells us how these rivalries play out when uninterrupted.

Before we explore more of them, let’s look at what happens when one side “wins”.

The Victory Turn

When we outlast an external foe we get what we want but lose ourselves. This is a cruel irony in the lives of individuals and civilizations. Victory is often not the reward we want, but an undermining of all we have.

Stressors stabilize us psychologically and physically, and when they’re removed we go to pieces. Exercise daily and you’ll be robust. Lay in bed for a few months and you’ll struggle to walk across a room.

This was explained well by English writer Samuel Johnson:

“I observed that Garrick, who was about to quit the stage, would soon have an easier life.”

Johnson: “I doubt that, Sir.”

Boswell: “Why, Sir, he will be Atlas with the burthen off his back.”

Johnson: “But I know not, Sir, if he will be so steady without his load.”

— James Boswell, Life of Johnson (1791)”

Societies without external threats frequently turn inward and find something unwanted. Then they try to cut it out, butchering themselves in the process. There are few more common targets in Western history than Jews.

Jews: The Eternal Scapegoat

Europeans welcoming Jews during high-pressure eras is common. Turning against them in peace is almost proverbial. Surrounded and outnumbered by Christians, they stuck out like sore thumbs and were obvious targets during a victory turn when external strife no longer distracted fellow citizens.

Three Examples of Jews Caught In A Victory Turn:

Medieval Spain: The Iberian Christian kingdoms welcomed Jews as they waged a bloody war against the Muslims of al-Andalus. But after the Reconquista ended in 1492, the Christians immediately expelled them, causing themselves significant economic hardship but winning “moral points.”

Medieval England: William The Conquerer invited Jews to England in 1066. He appreciated their business acumen and taxability as he pacified more and more of England and waged wars in France. The money Jews lent him was also critical. But once foreign and domestic threats receded, William’s descendant King Edward I ordered all Jews expelled in 1290 as part of a political bargain to increase his taxing authority3. England’s economy was hurt, but moral points were won.

Austro-Hungarian Empire: Emperor Joseph II’s 1782 Edict of Tolerance integrated Jews into society and improved their legal status as a way of fortifying the country as external threats loomed. Jews became an economic and cultural engine. But the Empire fell apart after WWI, and after Austria stabilized in its new constrained, poorer circumstances, Jews were scapegoated. They were driven from prominent roles in business, law, academia, and government, or fled the country in fear. Many of the marginalized remnants were slaughtered by Nazis in the 1930s

Now let’s put the two pieces together.

The Roman Republic’s Victory Turn

Three hundred sixty-three years passed between the Roman Republic’s foundation and the fall of its greatest enemy — Carthage. Of that, Rome was at peace for less than fifty years. The rest of the time? The Romans fought tooth and nail, trading one existential threat for another and gradually conquering Italy. Even when not at war, enemies loomed large in their imaginations.

During these unending conflicts, the Romans compromised internally, balancing the competing interests of noble patricians, business-savvy equities, and common plebians. When the plebians “seceded” five times in protests over their mistreatment by the patricians, the patricians always relented and brought the plebians back into the fold. They needed the plebians; any disunity was an opportunity for their ever-watchful enemies.

But the North African Republic of Carthage was always Rome’s real boogieman — a rich mercantile seapower gradually gobbling up the western Mediterranean.

Rome fought three titanic wars against Carthage before finally leveling the city. The ancient Roman historian Sallust tells us what victory did to Rome:

“…when Carthage, the rival of Rome's sway, had perished root and branch, and all seas and lands were open, then Fortune began to grow cruel and to bring confusion into all our affairs.

…These vices at first advanced but slowly, and were sometimes restrained by correction; but afterward, when their infection had spread like a pestilence, the state was entirely changed, and the government, from being the most equitable and praiseworthy, became rapacious and insupportable.”

— Sallust, The War With Catiline

Factionalism increased until it choked Roman decision-making. Looming problems went unaddressed. The reformers Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus were murdered, the first acts of political violence in Roman history. The republic choked on polarized factionalism.

The first Roman civil war started 58 years after Carthage’s destruction. The victors slaughtered their enemies but could not restore the amenity of their fathers. The final civil war began in 49 B.C., with Julius Caesar coming out on top. His enemies — who he’d forgiven and bought back into the fold — murdered him. His adopted son Octavian ended the Roman Republic forever.

Mexico United. And Then Disunited. And Then United Again

Mexicans didn’t agree on a lot in 1810, but they did agree that the Spanish Empire had to go. Groups with disparate visions of Mexico’s future united to drive Spain out, and they achieved independence in 1821.

A victory turn into polarization and civil war began almost immediately. The two main factions — the predictably named Conservatives and Liberals — turned on each other and took up arms. Each faction self-caricatured to take on more extreme versions of their original goals.

During the revolution, most liberals wanted to break up elite-controlled crime rackets, reduce clerical power, and reduce legal and economic discrimination against the natives. Most conservatives wanted to moderate that impulse and preserve the traditional power structure, but were open to some give. But during the victory turn, Liberals began demanding American-style democracy and Conservatives roared for a new monarch to rule over the nation.

Agustín de Iturbide declared the First Mexican Empire in 1823, but was driven into exile in less than a year. The replacement republic was unstable from the beginning. Control flipped back and forth between the factions.

It took another external threat to unite the nation. In 1864, French Emperor Napoleon III — supported by the highest-tier Mexican conservatives, clergy, and nobility — invaded and set up a puppet emperor.

The invasion gained control of central Mexico but unified the nation against the invaders. The conservatives lost popular support when they sided with the French, and most who’d been sympathetic to conservative ideas moved to the liberal camp.

The Mexican liberals gained the upper hand, drove out the French, and restored the republic. Liberals values such as press freedom, free speech, equality before the law, and representative government became — if not always upheld — then at least the ideal.

It’s All Greek To Me

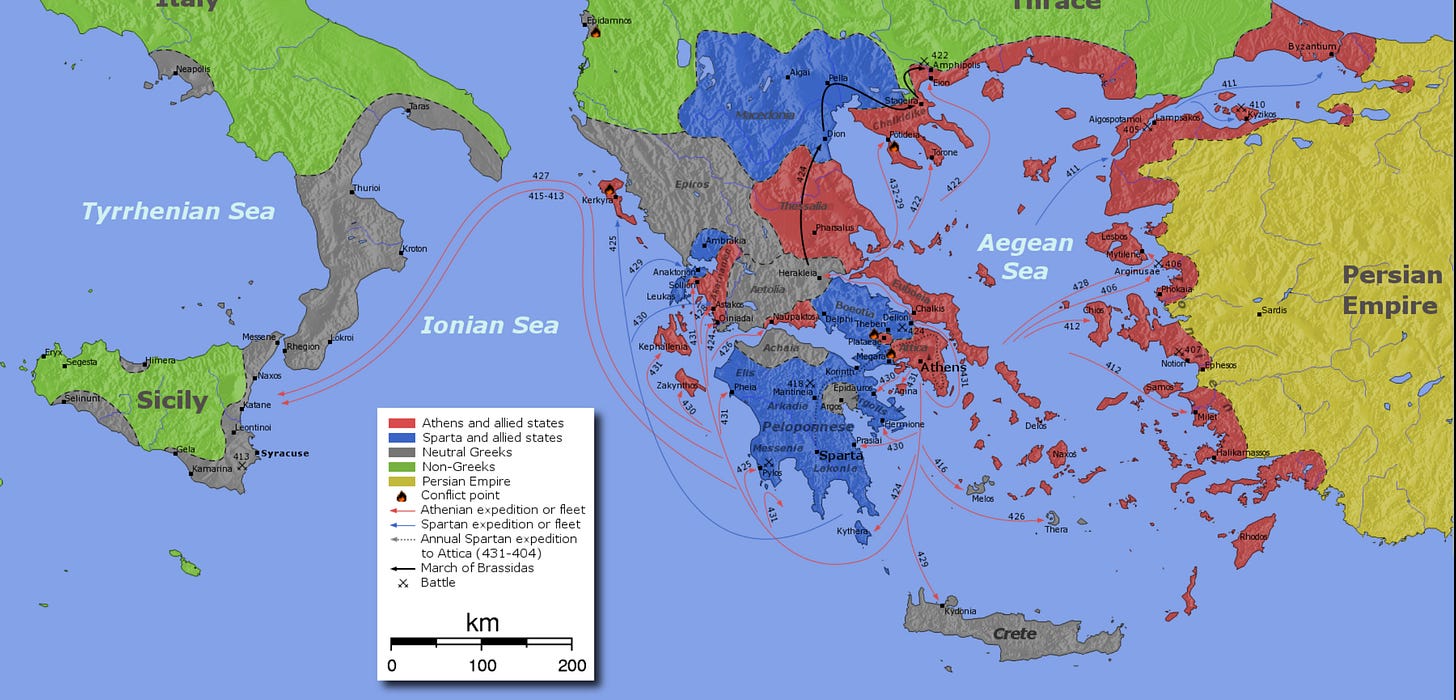

“Athens was to Sparta as sea to land, cosmopolitan to xenophobic, commercial to autarkic, luxurious to frugal, democratic to oligarchic, urban to villageois, autochthonous to immigrant, logomanic to laconic: one cannot finish enumerating the dichotomies”

— Anthropoligist Marshall Salins, Apologies to Thucydides

Salins covers the differences between Athens and Sparta better than I could. It’s hardly surprising that they did a victory turn into polarized conflict after uniting to free Greece from Persia.

Sparta’s oligarchy didn’t self-caricature during its cold war with Athens; there was little room for it to become more ideologically extreme. Rather, it entrenched in its traditions, refused to budge no matter what social forces pressed against it, and decided that other Greek cities straying from its ideals were threats that needed to be brought to heel.

Sparta had previously made ideological choices that set it up for the conflict. For instance, Spartans despised the proto-industrial production and trade that was the lifeblood of Athens. It adopted heavy iron bars as legal tender — totally impractical for trade, and so rarely used, putting a damper on what they despised. On the other hand, the standardized, high-value Athenian Obols were so well regarded that they became the legal tender of the whole eastern Mediterranean.

As early as the late 6th century B.C., Sparta began interfering in Athenian politics, overthrowing an independent-minded leader named Hippias and imposing an oligarchy. The Athenian lower classes rebelled and drove out the oligarchs, setting up an assembly of all male citizens which voted on all matters. This was the polar opposite of what Sparta wanted in a neighbor.

Athens:

Athens’s direct democracy fought off the Persian invasion at Marathon in 490 B.C., smashed a Persian fleet at Salamis in 480, helped free the Greek cities of Asia Minor and the Aegean from Persian domination, and grew increasingly cultured, rich, and imperialistic.

But as Athens and Sparta settled into a cold war following the Greek victories over the Persians, Athens gradually became more radically democratic. Reactions against Sparta drove many of these changes.

The most consequential was caused by a snubbing. In 464 B.C. a slave rebellion in Sparta threw the city-state into chaos. The Spartans called for aid, and Athens sent an army to help. The Spartans accepted soldiers from other cities but rudely sent the Athenians packing; they feared radical Athenian ideas would infect not only their slaves, but also the underclasses laboring to support the 9,000 citizens with full rights.

This snubbing infuriated the Athenians, increased anti-Spartan sentiment, and led them to ask: “How can we become even less Spartan?” “How can we be more extremely Athenian?”

According to Aristotle, the Athenian answer was removing most of the oversight authority from the Aeropaugus, a group of former elected officials charged with making sure democratic decisions were legal, that officials acted within the bounds of the law, and generally as a damper for the main assembly’s more radical plans. There would be little pushback against the majority’s whims going forward.

But the citizens themselves contorted away from the caution which was the hallmark of the Spartan state (which Sparta’s allies criticized them for). The generation of Marathon and Salamis acted with self-imposed restraint. Now the Athenians sought every opportunity to throw their weight around. The assembly began making stupid choices in the grip of passion, and often regretting it hours or days later, too late to change their minds. Cities were put to the sword for no good reason, talented generals were executed for uncooperative weather, and the quality of governance declined.

The most consequential mistake came during a shaky truce with Sparta. In 415 B.C., Athens launched a massive overseas expedition to conquer Syracuse, a powerful city-state in Sicily. Many Athenians knew this move would overextend the city. But demagogues convinced the Assembly that everyone would get rich and there’d be a glorious new empire to rule. The majority’s lust won out.

Doubling down on shortsightedness, the assembly striped the general Alcibiades of command of the expedition and put him on trial for alleged impiety and vandalism. He was a dissolute but talented commander, perhaps the only Athenian with the chops to pull off the invasion. Not wanting to be killed, Alcibiades fled to Sparta where he began giving the Spartans excellent military advice. Meanwhile, the Athenian assembly handed command of the Sicilian campaign to a cautious commander who’d earlier argued in the assembly that the campaign would be a disaster. The assembly ordered him to lead it anyway. The result was what you’d expect.

The defeat in Sicily crippled Athens. Sparta took advantage of their weakness and conquered their old enemy. They installed the most unAthenian form of government — an oligarchy. But it wasn’t Sparta that defeated Athens. Only the Athenians could manage that.

The real beneficiary was Persia. It couldn’t match Greek arms, and its ideology won no hearts and minds. But Persia was rich and began to fund whatever Greek faction was losing. If that side began to win, it would fund the other. It reconquered the Greek cities of Asia Minor without opposition by funding polarization.

The exhausted and polarized Greeks stood no chance against Alexander the Great’s Macedonian Empire, which conquered them with little trouble.

Counterexamples:

I’ll discuss the pressure cooker dynamic’s absence from certain eras of history and what conclusions we might draw from this in a future piece.

But just to emphasize that it’s not inescapable, let’s consider one aberration.

The French Revolution.

It’s not surprising that the nobility of Europe didn’t like the extremely egalitarian French Revolution. It’s not surprising that they went to war to crush its ideology. But it is surprising that Europe’s full-throated opposition didn’t unite France’s warring factions. The French continued their internal blood bath while fielding huge armies that whipped every coalition Europe could throw at them.

This simultaneous internal and external polarization and conflict is not very common in history, but not unheard of. Usually, when

Escaping The Pressure Cooker

I’m wrapping this up here because this analysis is getting overly long, but my notes file has another half dozen examples, and I suspect I could easily make this article four times as long if I gave it more thought.

But I think we’ve seen enough. There are clear parrels between these historical pressure cookers and the one we’re stuck in. If you zoom out far enough, you see that it’s more the norm rather than the exception.

Over the next few weeks I’ll suggest several ways we might be able to escape our pressure cooker cycle, and what individuals can do when society seems dead set on conflict.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

I found this example in David Graeber and David Wengrow’s. “The Dawn of Everything,” which explores schismogenesis

Goldschmidt, Walter. “The Problem Of Yurok Anality"

He also didn’t have to repay his significant debts to Jewish money lenders, which must have been a nice incentive as well.

The Yurok and the Kwakiutl are not separated by the Klamath River. They live 700 miles apart. The Yurok are in Northern California and the Kwakiutl live in northern Vancouver Island and the central BC coast. They were never neighbors.

Spain from the article: "But after the Reconquista ended in 1492, the Christians immediately expelled them, causing themselves significant economic hardship but winning “moral points.”"

Spain from Wikipedia: "The start of the [Spanish] Golden Age can be placed in 1492, with the end of the Reconquista, the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the New World, and the publication of Antonio de Nebrija's Grammar of the Castilian Language."