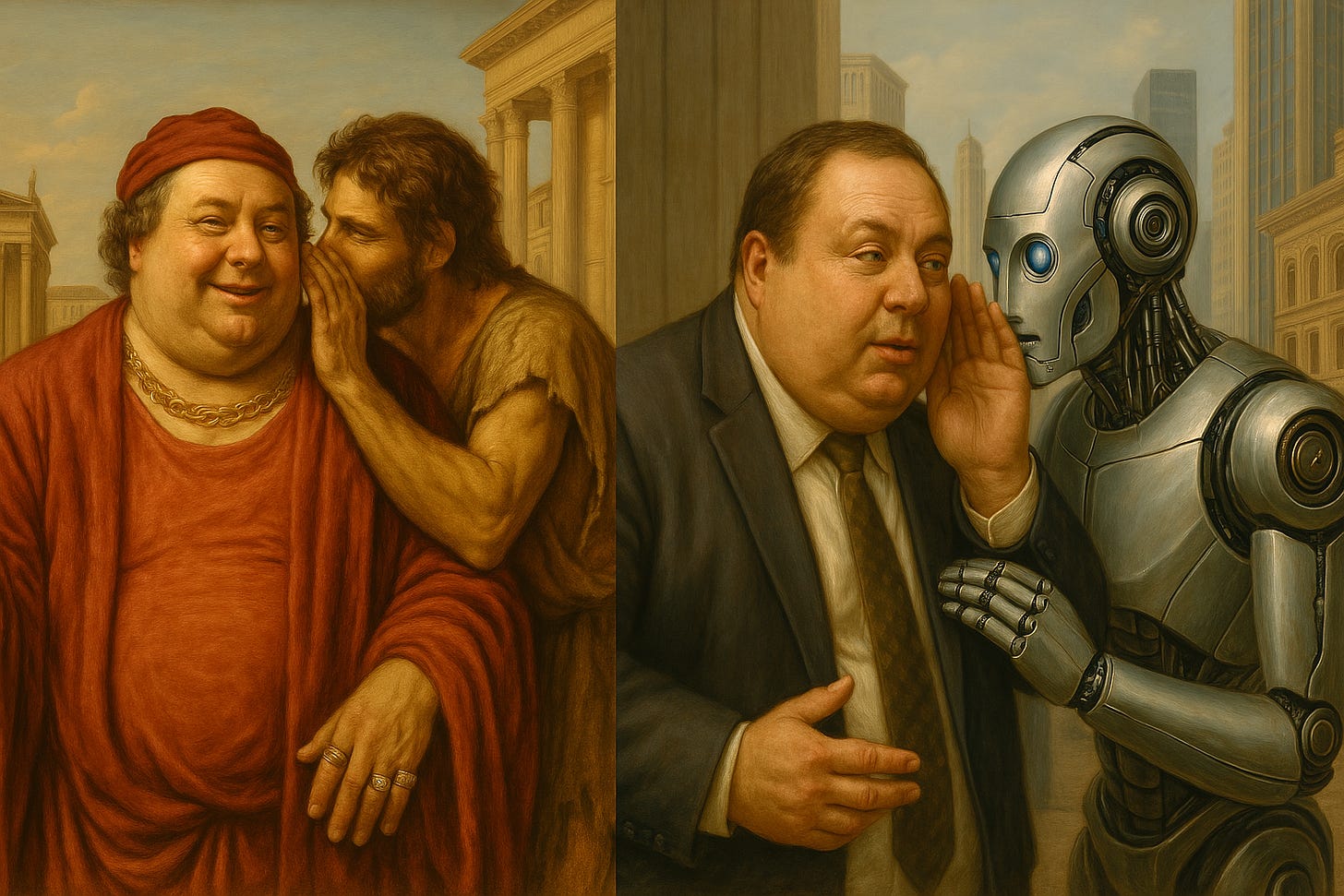

We rely on memory slaves and think nothing of it.

The ancient Romans did too, but their memory slaves wore shackles.

If our cost is merely the atrophy of obsolete recall abilities — a little brain fog that Chat GPT or Alexa can dispel — it might be worth it for the convenience. Maybe.

But if the living memory slaves of ancient Rome — nomenclatores servi— are any indication, the cost of offloading important memories and ideas to an external entity or technology is not merely poorer memory and function, but perhaps even a degradation of our humanity.

The Stoic philosopher Seneca tells us of a rich man named Calvisius Sabinus who took this practice to an extreme — “I never saw such a vulgarian with such a fortune.” (Letters, 27).

Sabinus had no interest in studying philosophy or anything that might improve him. His acquaintances? He mostly forgot their names, confident that his nomenlator could supply them when required. He kept the man by his side when he was out and about so he could address his many hangers-on by name with a jocular slap on the back.

But Sabinus knew ideas and information were prestigious and useful, even if he didn’t care to retain them himself.

“So he devised an expedient: he spent a great deal of money on slaves, one of whom was to know Homer by heart, another Hesiod, plus nine more, each assigned to one of the lyric poets…”

He not only paid a fortune for these highly-educated slaves, but sent them to study with the best teachers of poetry and mnemonic technique so they could retain it all.

At dinner parties, he stationed these slaves beside his dining couch and asked to be supplied with quotes and witticisms relevant to the discussion.

“…yet even though he regularly asked them for verses to quote, he often came to a halt in midsentence,” unable to even remember the entirety of the short bon motes whispered in his ear.

Chat GPT As a Memory Slave

And so we see the slippery slope our modern age presents. Never has it been easier to offload knowing to an external entity. We can effortlessly summon them for an information feast. It’s truly incredible. But convenience and efficiency have costs.

LLMs are the cognitive equivalent of our just-in-time supply chain model — great for increasing efficiency and decreasing overhead costs, but at the price of fragility. This is the Chat GPT and Google era in a nutshell. When we embrace these tools to the hilt we become enslaved to them, incapable of thinking clearly without their assistance, and maybe not even then.

Seneca’s rich vulgarian might seem an extreme example, but the diminishment of slave owners was a worry for the Romans.

The Lex Fabia de Numero Sectatorum, passed around 64 B.C., outlawed nomenclators in political campaigns, probably because they led to the false appearance of knowledge and advantaged the wealthiest. It had become apparent that candidates often didn’t know their constituents or their concerns but merely had an army of memory slaves who were good with names and details. According to Plutarch, the Stoic Philosopher Cato the Younger ran for office that year and was the only one to observe the law, using his own memory to connect with Roman Citizens and hear their concerns. The other candidates found it impossible to give up their nomenclators — they’d become too dependent.

In De Agri Cultura, Cato’s ancestor Cato the Elder’s warns landowners to personally manage their estates and not delegate everything to slaves. Those who didn’t stay involved ended up bamboozled, out of the loop, and helpless. They knew nothing about agriculture and ended up making poor decisions.

One of Tacitus’s critiques of the emperors Claudius and Nero is their near total reliance on slaves and freed slaves to do not only all the work, but also much of the decision-making. These dependent emperors didn’t have enough contextual knowledge to make heads or tails of the reports the slaves brought them, so they either told the slaves to decide or were manipulated by those very slaves and the flattlers around them. Their courts grew increasingly lazy, corrupt, and disconnected from the empire they was supposedly running.

We’ve now got 3 years of studies on the effects of large language model usage by humans, and the picture lines up with the slave dependence the Romans worried about.

The problem actually started in the 2000s. By 2011, researchers had found that search engines led to the memory of regular users working differently. Instead of remembering information, their minds remember where to search for information (their computers)1.

And in 2019, before large language models arrived, researchers found heavy screen use by adults harmed learning and memory, damaged mental health, and increased neurodegeneration. Among adults aged 18 – 25 it led to a thinning of the cerebral cortex, the brain’s outermost layer responsible for processing memory and cognitive functions, such as decision-making and problem-solving2.

With LLMs like Chat GPT, researchers discovered another layer of effects. They describe what users do with them as “cognitive offloading,” which applies to using any external tools to reduce the cognitive load on peoples’ working memory. Cognitive offloading to AI is associated with much less critical thinking (r = -0.75)3.

A study of students using LLMs shows reduced cognitive load, weaker engagement with their subject matters, and weaker reasoning in their analyses4.

A mixed-methods empirical study concluded:

“Our research demonstrates a significant negative correlation between the frequent use of AI tools and critical thinking abilities, mediated by the phenomenon of cognitive offloading.5”

It appears heavy AI users will head in the direction as Seneca’s foolish vulgarian — functioning at reduced capacity, unable to think straight, and dependent on external entities to handle cognitive load.

A Life Without Slavery:

It’s possible to use AI without diminishing ourselves. AI tools could be designed to push us to be better, but will they? It was in a Roman slave’s interest to keep their masters dependent, and AI companies are similarly incentivized.

I expect most humans who can access AI — and 52% of Americans already do — will go for easy mode. They’ll offload as much memory and critical thinking as possible, and they’ll pay for it. They will be less than they could be.

But I also expect that just as part of the population eats healthy food in the face of the deluge of processed junk, and a part exercises amid our sedentary culture, some will decide some things cannot be offloaded. Some things must be known by us.

Seneca suggests our private philosophy of life, certain facts about the world, and critical thinking skills are for us to master, even if they take effort — “This matter cannot be delegated to someone else,” he said.

We might be rich enough to buy AI assistance, but Seneca insists, “No man is able to borrow or buy a sound mind.”

So what are we to do?

I think embracing the mnemonic techniques of Seneca and other leading thinkers of Antiquity and the Renaissance is our best bet. What is of value to you? What expertise do you need, and what will keep you steady? This is what we must cognitively onload.

We need to learn things quickly and never forget them, and the polymaths of antiquity had powerful techniques for doing just that. Check out my course, Memorize for Meaning, for more info on being a free-thinking human in an increasingly cognitively-constrained world.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

Sparrow, B.; Liu, J.; Wegner, D.M. Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips. Science 2011, 333, 776–778.

Neophytou, E, et al. Effects of Excessive Screen Time on Neurodevelopment, Learning, Memory, Mental Health, and Neurodegeneration: a Scoping Review. Int J Ment Health Addiction 19, 724–744 (2021).

Gerlich, M, et al. AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking. Societies, 15(1), 6.

Stadler, Matthias, et al. Cognitive ease at a cost: LLMs reduce mental effort but compromise depth in student scientific inquiry. Computers in Human Behavior Volume 160, November 2024.

Gerlich, M. AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking. Societies 2025, 15, 6.

In Plato's "Phaedrus" Socrates says the same thing about writing - it makes us stupid and forgetful. Plato would probably have seen Substack as a place full of opinions and no knowledge because of very little real dialogue and no true dialectic. Seneca himself thinks along the same lines throughout his writings - we should be brutally selective about what we fill our heads with. In his opinion, the *only* kind of knowledge that we can justify spending time and mental bandwidth on is knowledge about what is good and bad. Everything else are highly destructive distractions.

"To want to know more than enough is a kind of lack of control."

- Seneca, Letters 88.37

What can't be delegated to others is the task of becoming wise. Other kinds of literary activity allows for assistance, as Seneca says in the very letter you have been quoting.

Interestingly, I just this weekend picked up a little volume at my kids' school book fair entitled How to Memorize Scripture for Life: From One Verse to Entire Books, by Andrew Davis.

I'm a hardline opponent of AI and I don't use it at all and never will, and I've been working to retrain myself to either remember things or look them up manually in a book or by going to a specific website I've chosen myself rather than "googling it." I read Fahrenheit 451 decades ago, around age twelve or so, and the idea of people meeting in the woods to recite memorized passages or whole books really stuck with me all these years. Currently I'm reading A Canticle for Leibowitz and again finding myself considering those moved to become "memorizers and bookleggers." Speaking as a person of faith: seems that God is influencing me to develop these skills. Thanks for the articulation as to some of the reasons why.