Find This Before It Disappears Forever

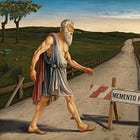

My advice for the young

The men with AK-47s wanted bribes.

I was happy to pay because I knew I’d find less of me beyond their checkpoint 100 miles from the Myanmar-Thai border, and less of what followed me like an all-devouring plague.

Even back in 2011, with the closest internet connections and the biggest Asian outposts of modernity far away, what produced me was leaking in:

The happy Burmese soldiers, surprised to see an American roll up on a motorbike, wanted their bribe in American dollars rather than their kyat — they knew where the value was.

They wanted to practice their limited English with me rather than talking in my limited Thai — they knew the language of the future.

"Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn," the one who didn’t look old enough to shave repeated, giggling, his heavy accent tripping over the improbable Gone with the Wind quote — He believed the bootlegged DVDs streaming across the border were superior entertainment to whatever existed in his jungle backwater.

I was on a 26-month South Asian work/backpacking jaunt, but rarely got far enough from the western air to get more than a breadth of something older and other. So when I wasn’t running my one-man business in internet-wired modernity outposts I ventured into the hinterlands — into the past. I traveled to cultural hotspots, visited Buddhist monasteries to indulge my interest in meditation, worked on farms, and talked to regular people when the language barrier wasn’t too extreme.

I wasn’t after an exoticized fantasy. I’d seen enough of the world to know romanticizing vanishing cultures is a mistake; what passes for modern western culture is, on net, often better than what it’s erasing.

But “superior,” “efficient,” and “poverty-destroying” can be maddeningly monolithic and bland. We choke on it, unable to think straight for lack of a robust other to push back against our follies and certainties.

Self-Destroying Birds

“But this one thing I know: all works of mortals are doomed to mortality. We live in the midst of things destined to die.” — Seneca, Letters, 91

Papua New Guinea’s Birds of Paradise are incredible, but they evolved in a decadent bubble with ample food and no predators. This competitive void allowed them to pour their evolutionary potential into awe-inspiring reproductive displays and plumage. No sane person would want them gone; they’re wonderful to behold. But so defenseless are they that the introduction of common housecats in their jungles would quickly doom them all.

Many foreign cultures are like these birds — beautiful, irreplaceable, but ill-equipped to compete for mindshare. It’s worse because they have a death wish. They’re actively importing the mangy cats that will destroy everything they are. They’re importing us.

This is not some future possibility. This century has seen 200 languages and countless oral tales disappear. Venice is a hollowed-out Disney theme park of renaissance culture, and Florence isn’t far behind. The glass towers of Bangkok look little different than those of New York, Bogata, or Nairobi. Jeans, athleisure, and American pop music are the “second languages” of everyone’s culture, just as English is now the second language everyone speaks. Everyone is a capitalist. All ethics has come down freedom from and freedom to.

The frictions and inefficiencies keeping modern Western culture at bay are mostly eroded. Those putting up new barriers — China’s Great Firewall — find them sufficient for tyranny but insufficient for protecting minds from the virus of us.

The inexorable spread of the internet and smartphones will carry our mind virus into remote deserts and tundras. AIs — Western and Chinese models — aren’t neutral fact dispensers but prophets of western modernity, so wrapped up in our way of thinking that they don’t even know there’s a different way to do it.

Only fools make predictions, but in this Darwinian struggle, it seems there will be significantly less cultural and mindset diversity in twenty years. That’s probably not a good thing.

What the Future Will Lose:

Much of the other I saw wandering the earth in my twenties and thirties is already gone, perhaps never to return.

I urge everyone to see what’s left of it before it’s swept away completely, particularly the young who’ve known nothing but continuous internet connections and smartphones.

The best places to visit are usually cheap — you might consider Cambodia, Laos, and after the recent drop in crime, maybe El Salvador. If you can manage it, save up some money, quit your job, and backpack around for a few months. Don’t stay in major cities or where westerners go. Head out into the countryside and visit third-tier cities and towns.

But why? After all, I agree with Seneca’s general take on travel:

“All your bustle is useless. Do you ask why such flight does not help you? It is because you flee along with yourself. You must lay aside the burdens of the mind; until you do this, no place will satisfy you.” — Seneca, Letters, 28

Most go abroad to escape — themselves or their lives. This is folly. Wherever you go, there you are. You might experience pleasure getting hammered on tropical beaches or admiring art in museums, but I wouldn’t suggest you’ll miss anything critical if you stay home.

But Seneca’s travel critique is of his time. His itinerary options were limited to the Hellenistic Mediterranean. While Roman civilization was ascendent, Roman poverty, disease epidemics, and technology weren’t markedly different from neighboring civilizations.

We no longer live in that world. People in developed countries exist in weird bubbles with warped perspectives. We don’t see clearly, but we might gain four things by visiting something other.

The Delluded Individual

Modern individualism is alien to world history, and skews our perspective on what’s ethical and worth pursuing. This becomes apparent if we immerse ourselves in radically different cultures, which now mostly exist on the periphery.

In “The Righteous Mind,” psychologist Jonathan Haidt describes a “red pill moment,” where he recognized the “possibility that there were alternative moral worlds in which reducing harm (by helping victims) and increasing fairness (by pursuing group-based equality) were not the main goals.”

Most westerners I know suffer from this delusion. Most humans don’t think harm reduction is the be-all, end-all of ethics, and even the West used to have different views. Many of our ethics and philosophy come from ancient Greece, which had very different “allegiance rankings” than us.

In Greek city-states, the ranking was usually:

City State (Polis)

Family/Lineage (Oikos)

Self (Arete)

Ethnicity/Culture/Religion (Hellenism)

In much of Asia:

Family (Confucian ideals, lineage obligations)

Culture (Confucianism, religious duty)

Self

Country (allegiance to monarchs/rulers above states)

In Mexico:

Family

Community (Local identity, usually regional or indigenous).

Nation

Self

The world is shifting toward the west’s me-first individualism, where unrestrained freedom is the goal. But as Jonathan Haidt points out, “When societies lose their grip on individuals, allowing all to do as they please, the result is often a decrease in happiness and an increase in suicide, as Durkheim showed more than a hundred years ago.”

The West’s decline in fulfillment and happiness as we’ve taken freedom to new extremes echo this idea. Time spent abroad helps us look beyond our monoculture and see other peoples’ ideals. Some of those ideals are worth borrowing.

Inexplicable Happiness:

I’ve seen it again and again: people living in poverty and skirting the edge of hunger but somehow remaining happier and more cheerful than half the people I know in abundant western countries.

People insist they’ve got lots of stuff to complain about, but historical analysis shows this is nonsense. Being confronted with such “unreasonable happiness” is a rebuke to us all. It drives home that happiness is a choice. The parts we control, and the way we frame reality, can turn our lives into a hell or a heaven.

My inclination leans dour, but I’ve made real happiness headway over the last 15 years. Seeing so many materially worse off people enjoying their lives made it hard to escape the fact that I was being a fool.

Gratitude:

The people with missing limbs puzzled me at first. They begged on street corners throughout Southeast Asia, leaning on crutches, one pant leg empty. Were they victims of landmines and wars? Some were.

But someone explained that most were polio victims. It was rampant as recently as the 1980s, and many had their atrophied limbs amputated.

But look around and you’ll see a miracle — the youngest generations have grown up without war and with a jab of polio vaccine. They’re missing no limbs, and everyone understands what happened and is grateful.

Our society has had it so good for so long that we’ve lost perspective. There are no living reminders of what the bad-old-days were like. All those limbless men can remind us of what we have, as can the fields of bones.

It’s hard not to be grateful for vaccines and peace when you visit these places. I suffer from autoimmune issues, severe allergies, and other health problems, but my eternal rejoinder to the pain they bring me is this: But I’ve still got legs! I can go running under the stars. I can dance!

There’s so much to be grateful for, and all it takes is stepping outside our bubble to see it.

Get Free of the Monoculture

When the monoculture and internet access blanket every inch of the earth, I suspect people will create small bubbles of the past to escape into for short periods, erecting creative masts to stay grounded and focused.

Mt. Athos isn’t going to admit you, and you’ll probably balk at Amish lifestyles, but there will be a craze for meditation retreats, unwired intentional communities, and farm stays.

Until then, third world countries still offer the best option for escaping our monoculture and the internet.

Go find it before it’s too late.

If you can’t, I’ve got three suggestions:

Read old books from before the monoculture, particularly these.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

It’s fairly easy to be unhappy in today’s world. I mean, I agree with your take and I’ve spouted it often to my wife and kids. But even though I myself can find personal satisfaction and happiness wherever I am, concern for my family, my community and my nation and the world can make me very unhappy indeed.

Jesus was a man of sorrows, acquainted with grief. There’s a lot to feel sorry for, even in America where rich men in big houses drown their pain in alcohol and pills, divorced and unloved while bums living in a culvert gathered round a campfire, laugh and embrace and keep each other warm.

Not only are you expanding my mind but now you’re expanding my bookshelf with the recommendations at the end.

Most of me appreciates you aside from my frugal side…