How America Can Ride Out Our Polarized Firestorm

Ways to stop America from tearing itself apart.

Why is California a tinderbox? Why do vast infernos rage from mountain to sea?

Because it’s dry?

Climate change?

Irresponsible campfires?

No. California burns because there aren’t enough fires there.

This oxymoron — this inconvenient fact — hints at why America fell into polarized infighting not long after its great triumph.

Fires have always burned in California; nature and natives started them. Ten thousand small fires a year exhausted California’s combustible fuel, rarely leaving enough for an inferno1.

The result was a different sort of California. The dense forests weren’t there 200 years ago, but were interspersed with fields and thickets providing habitat for a wider range of species. Fewer pests and pathogens and mild fire stress meant healthier, robust trees.

If modern Californians were willing to let chaos reign on the micro-scale, they too might escape apocalyptic firestorms while gaining diversity and resiliency on the macro scale.

The same could be said for American politics and polarization.

It’s Always The Most Important Election

"When all government, in little as in great things, shall be drawn to Washington as the center of all power, it will render powerless the checks provided of one government on another, and will become as venal and oppressive as the government from which we separated."

— Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Charles Hammond, 1821.

The pundit was certain. He assured me through my dorm TV that the 2004 presidential election was the most important in American history; everything was at stake.

His successors have repeated the claim every four years. On one hand, this is absurd. They can’t all be the most important election. Fate doesn’t always hang in the balance.

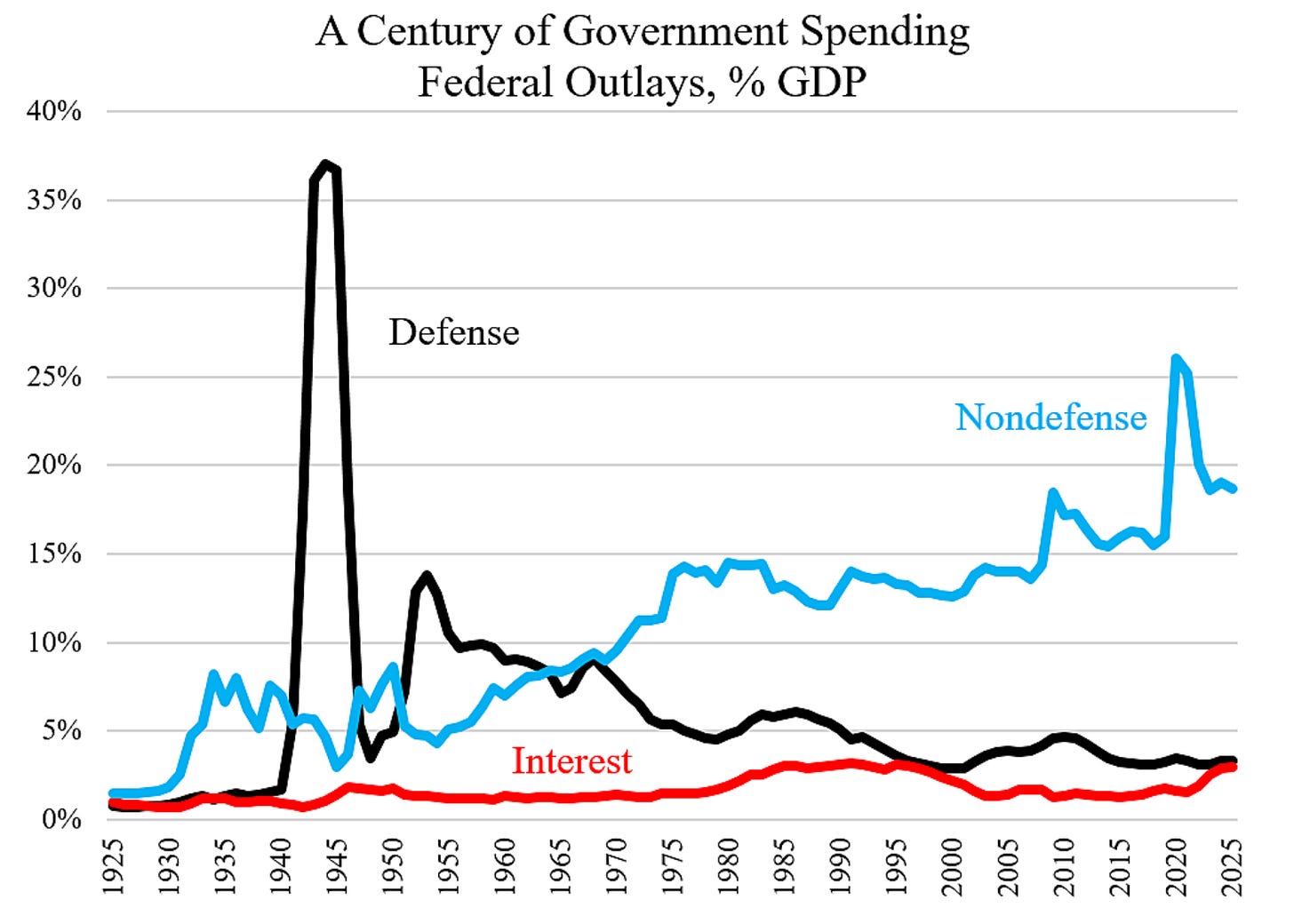

But in another sense it’s true. The US federal government has spent a century gradually confiscating powers once held by municipal and state governments and collecting ever-greater shares of the nation’s wealth — from 2.5 cents of every dollar in 1924 to 24 cents of every dollar in 2024.

After each four-year presidential cycle the government is a larger, less restrained juggernaut. It’s better at unilaterally affecting American lives. Since whoever controls the government has more resources and power after each cycle, each election is in that sense the most important.

Centralization has done us no harm, you might argue. We’re the richest country in the world and there’s no counterfactual small government US to compare ourselves to. Despite the federalization of wealth and power, the US remains more decentralized than most countries — a huge advantage.

But government structures matter. Institutions channel humanity’s mercurial swings, and design quality might mean the difference between civil war and constructive competition. This was once taken for granted.

“…all their institutions grew out of preventive measures taken to protect each other against their inner explosives,” the philosopher Frederick Nietzsche wrote of the ancient Greek cities. “This tremendous inward tension then discharged itself in terrible and ruthless hostility to the outside world: the city-states tore each other to pieces so that the citizens of each might find peace from themselves. One needed to be strong: danger was near, it lurked everywhere.2”

In other words, we probably don’t want the Greek model. Neither did the US founding fathers. When they took a stab at state design, they planned for the psychological shifts and infighting they knew would come. They traded efficiency for resiliency, and it’s worked pretty well through several polarized eras.

But it’s been 90 years since we last turned against ourselves. How will our increasingly centralized country stand up to the return of internal polarization, humanity’s oldest constant?

Based on what we know, not nearly as well as it would have 90 years ago.

How Countries Depolarize

“Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an ailment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be a less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.”

— James Madison, Federalist 10 (1787)

Researchers examining more than 200 episodes of pernicious polarization occurring between 1900 and 20203 found only 105 instances where countries significantly reduced polarization for at least five years. Almost half maintained their unity for a decade or longer, yet close to 50% later returned to pernicious levels of polarization.

The researchers concluded:

“these outcomes illustrate the difficulty of sustaining low levels of polarization, and they indicate that a cyclical pattern of polarization, depolarization, and repolarization may be characteristic of political life in many places.”

This shouldn’t surprise anyone reading my pressure cooker series. Cyclical polarization is the human norm.

A more interesting question: what depolarizes us?

Three-quarters of depolarization events came during or after “system shocks” that drove the “warring tribes” together — civil conflicts, foreign wars, regime/political change (primarily autocracy to democracy), and independence struggles against colonial powers.

Political or regime change drove 34% of all depolarizations. Even letting citizens vote in barely democratic “electoral autocracies” helped.

But here we run into a problem — the data set on pernicious polarization is light on Western-style liberal democracies. Liberal democratic institutions have historically protected against extreme polarization, making America’s entry into this category worrying and unprecedented.

So maybe a better question is, how do you make polarized people want to stick around?

The Quebec Formula

“Canada.” the old Quebecer mused, his accent thick. “Now…I think it’s ok. Thirty years past…maybe no.”

I asked French Quebecers if their province should be independent from Canada during a trip there last year. The dozen I asked thought not, but a few had grandparents and uncles still dreaming of la sécession.

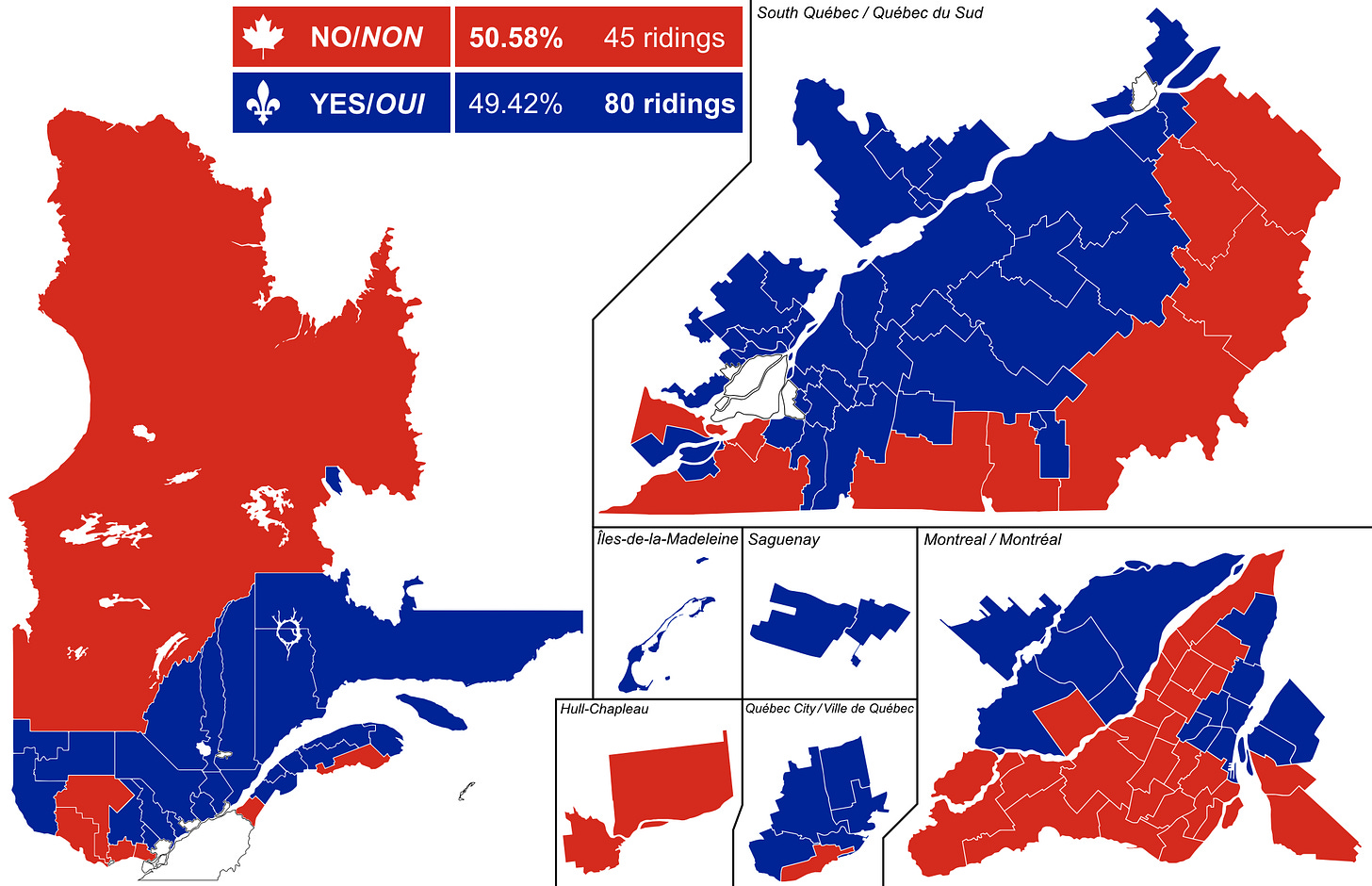

That’s surprising, since 49.4% of the population voted to secede in a 1995 provincial referendum. From the 1960s through the early 2000s, Canada was on the verge of losing its largest province.

The Quebecers were pissed. In 1965:

Quebec francophones earned 35 per cent less than anglophones.

If they didn’t speak fluent English they faced employment discrimination.

Higher education often required English fluency.

The federal government didn’t provide services in French.

English speakers were flooding in, and Quebecers felt they were losing their province and culture.

But in 2024, a poll found only 23% of Quebec wantined independence. They’d depolarized, but how?

Canada’s anglophone federal government took the unprecedented step of letting Quebec discriminate against them and do things it didn’t like, within limits.

It worked.

Canada’s “Asymmetrical Federalism” let Quebec opt out of many federal programs, regulations, and laws while receiving equivalent funding.

Want to work in Quebec? You’ll probably struggle and earn less if you’re not fluent in French. The government gives you six months after moving in before switching your services to French. The signs are in French. The restaurant menus are in French. Want to raise a child in Quebec? They’ll be educated in French and taught to love Quebec’s culture, no matter their native tongue. Quebec has tweaked its social programs, healthcare, and immigration programs to local tastes. Raw milk is banned in most of Canada, but legal in Quebec. Civil law cases utilize French-heritage norms instead of English-heritage ones.

It’s Not All Good

The ability to go their own way within the larger Canadian union won the Quebecers over.

This doesn’t mean Quebecers make fantastic decisions. They’ve made some weird mistakes. Stringent language requirements reduce external investment, and many large corporations and banks moved their headquarters from Montreal after the province doubled down on Frenchness4.

But those mistakes are Quebecer mistakes, not Canadian mistakes. That makes a difference in the great game of polarization.

The Amity of Decentralization.

“The bigger the unit you deal with, the hollower, the more brutal, the more mendacious is the life displayed. So I am against all big organizations as such, national ones first and foremost...” — Psychologist William James, Letters, Vol 2.

Decentralization doesn’t always work. Why has it kept Switzerland harmonious and Canada united when Yugoslavia, Sudan, and Czechoslovakia, broke apart?

Where great hatred exists (such as after ethnic cleansings and civil wars) and where minority groups are geographically isolated, “it may be difficult to imagine continuing cohabitation within a union,” one group of researchers concluded5.

But where polarized groups are interspersed and intertwined (as in the US) and haven’t started killing each other, decentralization offers what the researchers call a “relief valve.”

What’s the best strategy for decentralizing?

The researchers concluded that the top-down approach of a central government dictating uniform decentralization for each province/state often backfired. What worked much better was a bottom-up approach of regional governments negotiating for control of the parts of the governing portfolio they cared about.

This has three advantages:

More conflict plays out at the municipal and state level rather than at the federal level, burning up a lot of “fuel” that might cause a national inferno. A thousand small fires do not an inferno make. Any mistakes or wins play out on a local scale, letting others observe the outcomes. The goal isn’t complete harmony, but lots of dispersed small-scale conflict and “small bets" that can safely fail without shaking the nation.

People care less about fighting for control of the federal government, since more of what they care about is locally controlled.

Small private and public sector projects and programs are far less likely to fail and be delivered late or over budget while total success on mega projects is rare6. Small countries with lot of moderate volatility appear to have resiliency advantages that belie their size78. By offloading parts of the federal portfolio and letting states and cities fight over them, the US is more like many small robust countries instead of one big fragile one.

A Thought Experiment:

Imagine the federal government had one job: co-managing the Falcon International Reservoir on the Rio Grande River with Mexico.

Even if you’re a hydrology wonk, your interest in federal elections might drop 90%. You probably wouldn’t be concerned if “the other side,” took control of the federal government. Maybe you’d stop voting in federal elections entirely.

Now imagine the federal government had two jobs: managing the reservoir and deciding how many children each American will have.

Interest in who controlled the government would skyrocket. It would become a national obsession. Perhaps, if “the other side," won an election, you’d contemplate secession or war to protect yourself. You’d probably hate the “other side” for forcing their procreation preferences on you. This is an extreme example, but a good one for explaining why people are so polarized — we see outsiders forcing their preferences on us.

But it doesn’t follow that the optimum amount of federalization is zero. We tried an almost-impotent federal government from 1781 —1789 under the Articles of Confederation. The government was too weak to address America’s foreign and domestic problems. We need a federal government to do the things individuals, cities, and states can’t do. It doesn’t make sense for Iowa to have an airforce. Nevada won’t benefit from managing a DARPA knockoff. But maybe Massachusetts should have a greater say in how transportation dollars get spent.

The idea is “doing our own thing, by our own standards, together.” That means handing responsibility to the most local level of government that can sustain the complexity of the task. Complexity rises to the level that can handle it, and no higher.

Mutal Federal Disarmament

Just as the nuclear arms race between the US and the Soviet Union wasted resources and brought both sides to the edge of armageddon, no political party or state benefits from the federal status quo. Both sides lose as frequently as they win, and we’re tearing the country apart.

Liberals and conservatives would be wise to take a page from Soviet-US relations and begin to “mutually disarm.” We should deprioritize national pyrrhic victories and priorities battles we can win them — the local ones. To do that, we need to find some common ground.

What’s Ripe For Decentralization

“One solution fits all is not the way to go. All these cultures are different. The right culture for the Mayo Clinic is different from the right culture at a Hollywood movie studio. You can’t run all these places with a cookie-cutter solution.”

— Investor and philosopher Charlie Munger

Fears of outsider preferences and cookie-cutter solutions being forced on people drives national polarization. If you think the other side doesn’t have your interests at heart, it makes sense to preemptively go on the offensive to head off them off and force your preference on them. To the extent that we can reduce the possibility of federal interference in American lives without violating the Constitution, the nation will benefit.

Even in our polarized environment, several avenues for mutual disarmament decentralization are possible.

Presidential Reset

“The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create whatever the form of government, a real despotism. A just estimate of that love of power, and proneness to abuse it, which predominates in the human heart is sufficient to satisfy us of the truth of this position.”

— George Washington’s Farewell Address, 1796.

Presidents couldn’t originally unilaterally wage wars, impose sanctions, deny immigrants entry, and control the release of information. George Washington averaged one executive order per year. Lincon oversaw the Civil War while averaging 12. President Obama averaged 35. President Trump averaged 55. Much of our country is now run by fiat.

Since executive orders aren’t law-making instruments in the Constitution, they’re on shaky legal ground. The Supreme Court has spent 15 years bogged down in states suing the President to overturn often-unconstitutional executive orders. Depowering the president and repowering Congress would solve this because only Congress has constitutional lawmaking powers.

A good start would be legislation limiting the chief executive’s unilateral emergency and war powers to 30 days without congressional approval. Other legislation could limit how much a president could spend without congressional approval.

Perhaps this would increase gridlock, but gridlock isn’t the horror people think it is. For every good program that fails to pass through gridlock, there are four bad ones that never get through. A polarized Congress is probably better for the country than a moderate one9, and it will matter less if we can shift more power back to states, municipalities, and individuals.

Children:

People worry their children are being brainwashed by liberal/conservative/religious propaganda in public schools. This fear can be allayed by handing control back to parents and municipalities, and where necessary, states.

If the Department of Education had improved education outcomes since its creation in 1979, we could argue for its value. It hasn’t; student scores are stagnant. But it has retarded innovation, forcing schools and states to jump through regulatory hoops to access small amounts of federal cash.

The easiest fix is to abolish the department, hand student loan oversight to the treasury, move nondiscrimination oversight to the Department of Justice, and attach the rest of the budget to individual students. That means $3,000 - $4,000 for each of the nation’s 54 million students. The money would go to the parent, “education pod,” or public/private school teaching the child and boost education equality across the country.

The Supreme Court:

Most constitutional amendment attempts are dead on arrival, but a modest one might be uncontroversial enough to pass and effective at depolarizing the Supreme Court. It would:

Require the Senate to vote on presidential Supreme Court nominees within 90 days.

Require 65 votes rather than 51 to confirm a candidate. This would make far-left and far-right judges unlikely, since no party has held 65 senate seats since 1943. Bipartisan support would be required for each candidate.

A moderate Supreme Court is less likely to overstep its bounds and try to do an end-run around the legislative process to bypass federal gridlock.

Primaires and Ranked Choice Voting:

Closed primaries drive polarization by leaving only far-left and far-right candidates in the general election. They rarely represent majority opinion.

Alaska ended closed primaries in 2022 and replaced them with a single nonpartisan open primary. The top primary vote-getters advance to ranked-choice general elections. Moderate Republican Lisa Murkowski was the first elected under this system, and she’s proven herself willing to buck party orthodoxy.

Game theory explains how ranked-choice voting moderates candidates. You can’t only appeal to your base in a six-candidate election, but need to make sure you don’t alienate your opponent’s base. You want supporters of other candidates to regard you as at least ok, because they’ll rank you last if they hate you.

Ireland has used ranked-choice voting for a century, and has fairly nonpolarized politics.

Other US cities and states have moved toward ranked choice voting, and if expanded, this may prove a depolarizing influence on the federal government.

Deregulate The Money

The federal government sucks up much of the nation’s wealth, and there’s little left for states to tax. That means that most significant programs will involve federal grants. But federal money comes with strings attached. To get it, states need to tow the federal line.

Some of these regulations and restrictions are reasonable, but many stop states from going their own way. The federal government should take the Canadian’s Quebec approach and deregulate most grants, allowing states to use money more freely on their own priorities within broad categories (transportation, health, etc)

A Policy of Political Self-Doubt

“The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine that they can design…”

— Friedrich Hayek, The Fatal Conceit

Many oppose the kind of decentralization we’ve discussed here. They want their preferences enforced over the whole country, which means high-level political conflict and more polarization. This escalation ends with one of the seven unappetizing options.

I don’t claim my suggestions are ideal or sufficient, but merely in the realm of the possible and likely to help. The US is better constituted to ride out this storm than most countries, but its great size and diversity will increasingly push Americans into conflict until an external threat unifies us again.

If we’re to ride out this polarization phase, we need to have the flexibility to let a thousand small fires burn, and to suspect that we might not know what a town a thousand miles away needs. Municipalities and states need enough rope to hang themselves, and we have to understand that we won’t like many of their decisions.

People, towns, and states make lots of mistakes. But they’ll be their mistakes. Hopefully, that will be enough.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm. Twilight of the Idols and the Antichrist; or, How to Philosophize with the Hammer.

McCoy, Jennifer. Et al. Reducing Pernicious Polarization: A Comparative Historical Analysis of Depolarization

Cerniglia, Floriana. Et al. How to design decentralization to curb secessionist pressures? Top-down vs. bottom-up reforms

Ansar, Atif. Big is Fragile.

Taleb, Nassim. The Calm Before the Storm.

Baker, Scott. Rational Gridlock