"All men by nature desire to know." — Aristotle, Metaphysics, 1.1

Curiosity isn’t just a killer of cats and an enjoyable pastime, but a useful tool and problem solver.

Get curious about the world and you can’t stomach the distortions your tribe feeds you.

Get curious about others and drive collaboration, empathy, and justice.

Get curious about problems (not just annoyed) and discover innovative solutions.

Get curious about yourself and drive self-awareness and growth.

Get curious about ideas and become an autodidact.

I’ve also discussed curiosity’s role in our cognitive self-defense suite, which has become even more valuable as manipulative social media and AI slop colonize our mindscape.

But this is useless insight unless we can turn curiosity on. Is curiosity – and lack thereof — just genetic? Why are some people more curious than others?

In the Beginning:

“At once two things came to mind: fear and desire: fear of the threatening dark cave, desire to see if there was anything miraculous within it.” — Leonardo da Vinci, Codex Arundel

Everyone has experienced the boundless curiosity of children. They drive the less-curious adults around them mad with incessant questions.

But how do curious children become incurious adults? Do they puzzle out all the world’s mysteries between age 1 and 12, and thereafter rest in stolid, bovine acceptance of everything at face value?

Researchers have quantified the curiosity drop. Students display 2.36 “episodes of curiosity” per 2-hour stretch in kindergarten, but are down to just 0.48 by fifth grade1. Their curiosity probably isn’t being satiated through learning, but rather crushed by opposition.

In a Japanese study of 511 children between the ages of 9 and 14, those whose curiosity received a positive response from adults were not only happier, but prone to be more curious down the line2.

But in many elementary classrooms, student questions that don’t directly pertain to the assigned task are often rebuffed. Teachers tell children to refocus on their work, discouraging further acts of curiosity3.

Researcher Susan Engel heard an elementary school teacher tell a curious student, “I can’t answer questions right now. Now it’s time for learning,” which is funny, because that response probably ensures the child will learn less and less as time goes on and their curiosity is ground down to nothing. Curiosity is associated not only with information-seeking, but with motivation and learning persistence in the face of obstacles456, and killing it might be the death knell of our drive to understand and lifetime learning.

So perhaps its no surprise that in searching for student curiosity, Engel found an “astonishingly low rate of curiosity in any of the classrooms we visited.”

But however curiosity is killed, is there a way to revive it?

Reviving Curiosity:

“To know and to will are two operations of the human mind. Discerning, judging, deliberating are acts of the human mind.” — Leonardo da Vinci, Notebook XIX

Reading through the ever-curious Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, it’s the questions that strike you.

“The body which is nearest to the light casts the largest shadow, but why?”

“Why does the eye see a thing more clearly in dreams than with the imagination being awake?”

“What a thing is slumber! Sleep resembles death. But why do you not work in such ways as that after death you may retain a resemblance to perfect life, when, during life, you are in sleep so like to the hapless dead?”

Leonardo sees or reads something or has a conversation, and questions bubble up. He writes them down, mulls them over, and hypothesizes. Often, he doesn’t find answers, but a thousand new connections form which he is intent on investigating.

Sometimes, months or years later he returns to these gaps in understanding when he notices something new or has an ah-ha moment.

Questions lay at the heart of our curiosity, and it appears cultivating them might be a key to reviving it once crushed.

One of the most impactful curiosity increasers appears to be teaching students to brainstorm their own questions about what they’re engaging with instead of merely grinding through it or memorizing it by rote7.

This, combined with enough autonomy8 to pursue the questions they generate, appears to build up curiosity.

Curiosity Colonize The World:

I’ve watched my brain do something many times — it takes a topic I’m not interested in and transmutes it into something worthy of curiosity.

After observing this hundreds of times, I think I understand the process:

I have an existing area of interest.

While exploring this interest, I observe its connection to a thing I don’t care about. A question arises that begs an answer. Why is this boring thing touching the interesting thing?

Desiring to fully understand the thing I’m interested in, I’m forced to explore the uninteresting thing, which I think of as “idea colonization.” My interest has planted a flag and “claimed” this new distant land. Suddenly, the boring becomes at least mildly intriguing.

I then have a tiny “lit up node” in this vast area of greyed-out disinterest, connected to “the motherland,” via a narrow sealane, traversed by the occasional creaking galleon.

I notice other things touching this tiny lit-up node that appear important to understanding it. They are now relevant to my original interest, and therefore have become interesting in and of themselves.

As more greyed-out nodes are lit, more and more galleons are dispatched from the motherland to make the journey. Each newly-lit bordering node increased my curiosity.

In the end, it turns out that everything is connected to everything else, and therefore, everything is potentially interesting.

The Back Door:

We shouldn’t try to enter a subject by the obvious front door. It’ll be too boring. You’re unlikely to become obsessed with biology, the Franco-Russian war, or economics by cracking open a textbook.

To become curious about an obscure or boring thing requires us to find its backdoor connection to something interesting. If the skill of reading is boring, it’s probably because you haven’t found something interesting to read. The Pythagorean theorem seems dry until pyramids become intriguing.

Example: Teenager Likes Pop Music

I like a particular modern pop star who uses electronic music.

I watch an interview where they say they’re inspired by baroque styles. But how can that be? Classical music is so boring, so unlike the energetic, emotional style of today that rebels against our BS-filled world.

I learn that baroque music was a reaction against the more “intellectual” music of the Renaissance, and had the doctrine of affections (affetti) at its heart: the belief that music could (and should) summon emotional states—joy, sorrow, anger, awe. I listen to Bach, and I feel the emotions. I do a deep dive on what popstardom looked like in the 18th century. I find the “drop”, or climax, in Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G major is a lot like the gradual build-up and “beat drop” my favorite pop star uses in their pieces.

I am now interested in baroque.

Practical Steps For Curiosity

I suspect everyone has questions pop up as they explore life. But some people embrace them and others suppress or ignore them and follow “their task,” like the previously mentioned teacher wanted her student to do. We have to begin noticing and acting on our pings of interest if we want to reclaim curiosity, even if others want to corral us and force us to swallow “the message.”

But it’s equally important to be skeptical about our preconceptions. As Epictetus said, “…it is impossible for anyone to set out to learn what he thinks he already knows,” (Discourses, 2.2.17)

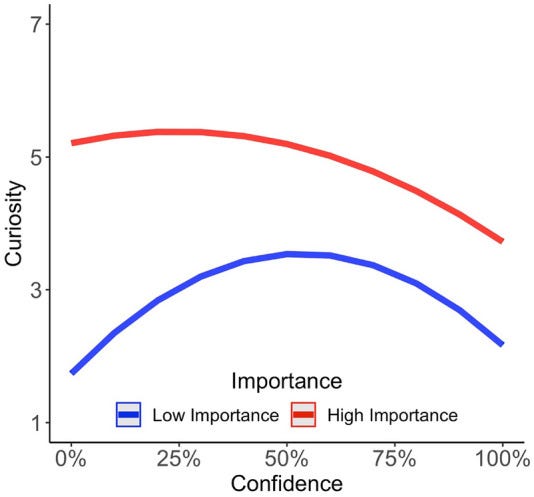

Researchers have discovered that curiosity follows an inverted U-shaped function of confidence, with the highest curiosity aligning with moderate confidence levels of knowing information9.

In other words, total skepticism (I can never know anything) and complete certainty (I’m already an expert) appear to backfire for curiosity. I like this method for developing worthwhile opinions in our confusing world.

More Bang For Your Curious Buck:

To understand anything, several “big ideas,” help. Almost every major knowledge domain has a few that can be brought to bear on most questions.

Economics by itself seems boring. It’s just dollar signs and trade balance reports. But once you see how it explains or informs almost everything to do with humans, it becomes a useful tool, and so is interesting in and of itself. You can’t understand the world without a basic understanding of economics.

Here are some “big ideas,” from four domains that will help you understand whatever you’re already curious about:

Psychology: Bias, Focusing Illusion Bias, Cognitive Dissonance, Hedonic Treadmill

Math: Probability and Uncertainty, Compound Growth, Fractals & Self-Similarity

Economics: Incentives, Moral Peril. 2nd and 3rd order effects, net profit margin.

Genetics: Gene-Environment Interaction, Trophic Levels, Carrying Capacity

For more on worthwhile economic ideas, check out this piece:

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

Engel, Susan. 2011 "Children's Need to Know: Curiosity in Schools" Harvard Educational Review.

Hirose, J. 2024 How do question-answer exchanges among generations matter for children's happiness? PLoS One. 2024 Jun 21;19(6):e0303523.

Engel, Susan. The Hungry Mind: The Origins of Curiosity in Childhood (Harvard University Press, 2015), pp. 87-89, 100; and “Children’s Need to Know: Curiosity in Schools,” Harvard Educational Review 81 (2011), p. 633.

Kashdan, T. B., and Steger, M. F. 2007. Curiosity and pathways to well-being and meaning in life: traits, states, and everyday behaviors. Motiv. Emot. 31, 159–173. doi: 10.1007/s11031-007-9068-7

Hidi, S., and Renninger, K. A. 2006. The four-phase model of interest development. Educ. Psychol. 41, 111–127.

Kashdan, T. B. 2006. Exploring the functions, correlates, and consequences of interest and curiosity. J. Pers. Assess. 87, 352–353.

Clark S, Harbaugh AG, Seider S. Fostering adolescent curiosity through a question brainstorming intervention. J Adolesc. 2019 Aug;75:98-112.

Schutte, N.S., Malouff, J.M. Increasing curiosity through autonomy of choice. Motiv Emot 43, 563–570 (2019).

Spitzer MWH, Janz J, Nie M, Kiesel A. On the interplay of curiosity, confidence, and importance in knowing information. Psychol Res. 2024 Feb;88(1):101-115.

Thanks for this post 🔥🔥🔥 🧨🧨🧨 !!!

In these "special" times, to be curious about why being curious (or not) is a curiosity ...

love