I’ve discussed how firm opinions leave us fragile and stupid.

So there are many things in life to which we should say, as the Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius did:

“You always own the option of having no opinion. There is never any need to get worked up or to trouble your soul about things you can't control. These things are not asking to be judged by you. Leave them alone.”

“But Andrew,” I hear you saying. “I can’t have no opinions! How will I survive without them? How can I vote? How can I raise children or run a business?”

You’re right that you’ll need loosely held working hypotheses to navigate the world.

But the problem is that you can’t develop many worthwhile opinions. Rational, well-thought-out opinions grounded in reality take months or years of diligent testing and research to form. You’re a busy human and there’s a bottomless well of things you might hold opinions about, so you’ll master few subjects. The alternative of unshakable faith in half-understood ideas is a recipe for disaster.

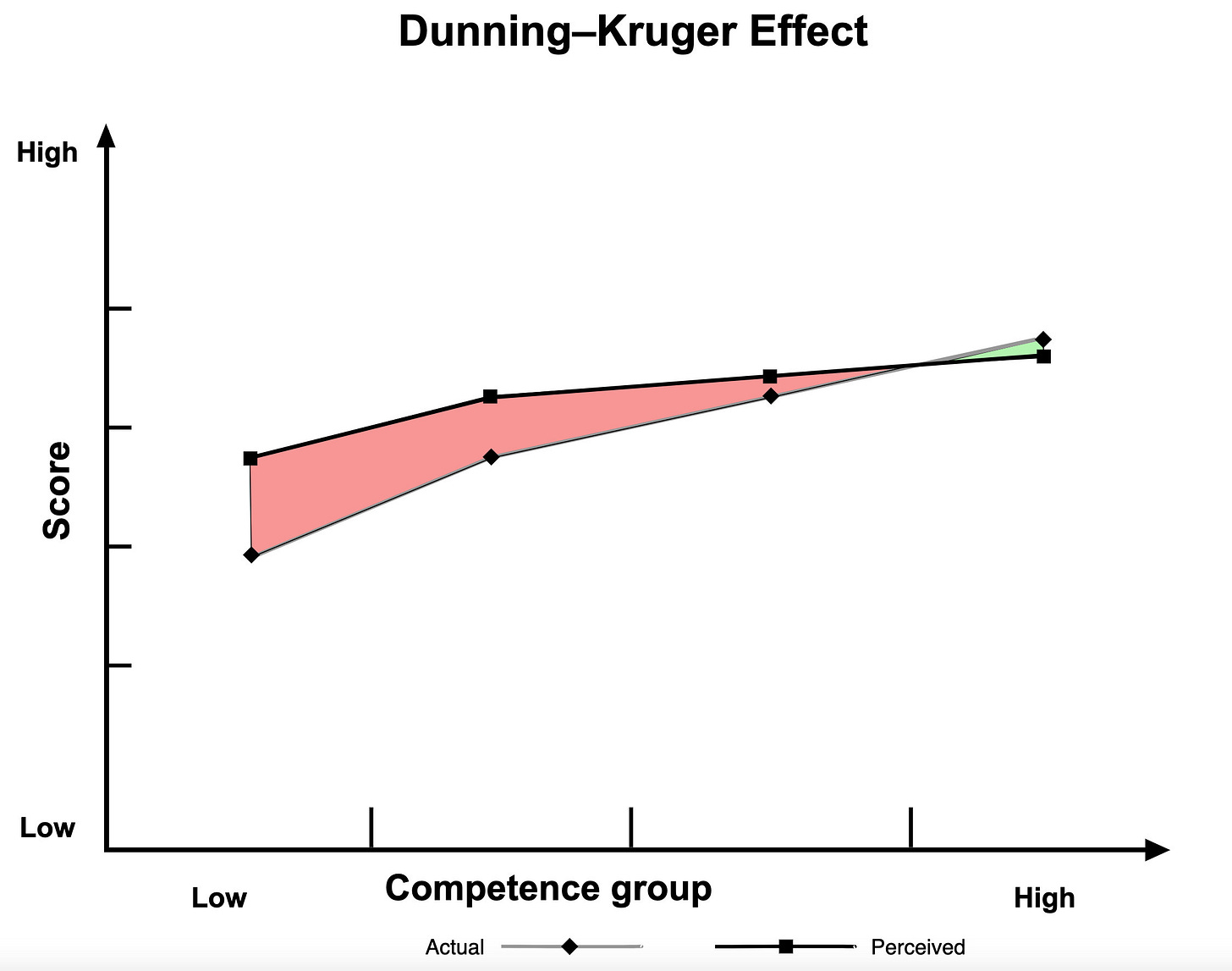

The ill-informed think their few facts constitute mastery while the titans of the field know their knowledge is incomplete and qualified. This is the famous Dunning-Kruger Effect1.

People of limited knowledge lack the perspective to grasp how complicated something can be, causing them to overestimate their knowledge or ability. When the knowledgeable insist something is complicated and uncertain, the ignorant falsely believe they understand it fully and the matter is decided. Mistakes and disasters are inevitable in this scenario.

It’s like my favorite (It’s self-referential!) apocryphal Mark Twain quote says:

“It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so.”

The Truth About Worthwhile Opinions:

Worthwhile opinions take work.

One method I’ve found effective is what I call the dueling books method. I pick 1-3 well-regarded books by subject matter experts from each side of an issue. I then alternate reading one from each side of the debate. This doesn’t result in mastery. Not even close. But I usually feel I’ve reasoned my way to a worthwhile loosely held working hypothesis by the end.

If you have the mathematical and statistical chops to interpret studies, reading many meta-analyses (not just the abstracts) can help you form useful working hypotheses. But unless you have long studied these subjects, it’s easy to fall into a Dunning-Kruger trap.

“Andrew!” you’re now yelling at me. “Your method is ridiculous. Who has time to read 2-6 books and the data from many meta-analyses for each opinion?”

Exactly! You don’t have time. No one does. So it makes it doubly ridiculous to have many firm opinions.

Some things really matter; put in the work to master them.

And the rest? Let them go and be free of the burden.

“These things are not asking to be judged by you. Leave them alone.”

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

Kruger, Justin; Dunning, David 1999. Unskilled and unaware of It: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77 (6): 1121–34.

Fantastic post. I love the concept of uncertainty in almost every aspect of life. Open-mindedness reduces stress and encourages growth. Nothing wrong with beliefs and opinions assuming you can maintain rational control when they’re challenged. If not, good opportunity for reflection or the great suggestions you made like dueling books!

Good read. I think this also speaks to why it’s important to value expert scientific consensus over what simply resonates best with you.