I was obese as a young man, but lost the extra weight more than twenty years ago.

I’m often asked how I keep those extra forty-four pounds off, and if it’s a struggle.

The answer to the second question is that keeping it off takes effort and attention, but it’s never overwhelmingly difficult because of the habits and mindsets I’ve inculcated.

The first question is harder to answer. It’s easy to list the tangible acts that achieved my weight loss, but everyone who’s dieted has likely encountered these tactics before, and they’re interchangeable. Tactics can cause weight loss but don’t necessarily lead to it.

The more-true answer to the HOW question is that Stoicism — or at least the mental reordering begun in my late teens and early twenties when I started reading the Roman Stoics — forced me to lose weight.

Yet this answer is also unsatisfying. Stoicism is multifaceted and not clearly linked to body weight. One could be obese and a good Stoic. So what is it about Stoicism that improved my weight regulation?

The title of this post is Stoicism vs. Mindfulness, as if they formed a natural dichotomy ripe for comparison. The truth is messier. Although Eastern-style meditation has no analog in Stoic philosophy, Stoicism demands mindfulness. Stoics pay attention so they see how their thoughts, words, and deeds stack up with the four Stoic virtues — wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation.

I find paying close attention to eating valuable for weight control in-and-of itself. But I suspect attention’s role in letting me assess my character vis-à-vis food is the bigger piece of the puzzle.

But is this just a crackpot theory?

To explore the idea, I’d like to look at three steps by which Stoics might mindfully interact with food, and assess what research tells us about the closest approximates to these Stoic practices we have data on.

Step One: Prosoché (Paying Attention)

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus defined a goal of Stoicism as “to strive continuously not to commit faults,” with the hope that by “never relaxing our attention, we shall escape at least a few faults” (Discourses 4.12.19)

Eating without fault requires living up to the virtues of justice and moderation, so Stoics pay attention while eating to see if they’re doing this.

What happens if we don’t?

Men and women randomized to eat a meal while watching television ate 36% more calories of pizza and 71% more calories of mac and cheese1. Subjects dining with friends and having a conversation, and so presumably giving less than full attention to eating, ate 17% more calories than when they dined alone2.

On the other hand, when study participants were asked to give their full attention to eating lunch, and then offered a snack of cookies two hours later, they ate 45% fewer calories from cookies than those not instructed to eat mindfully3.

A meta-analysis looking at nine mindfulness-based weight loss interventions and 1,160 participants found a moderate 7.5 lb weight loss after around four months, and a large reduction in obesity-related eating behaviors like binging. There was significant variance in the types of mindfulness interventions studied, however4.

So it seems that doing nothing more than monitoring the process of eating, in line with Stoic teaching, may cause us to eat less, which could influence body weight.

Step Two: Pause Before You Act

Paying Attention isn’t a cure-all. You might pay attention and yet experience powerful cravings your rational mind finds immoderate (though I find attention to eating does reduce them). Maybe this looks like an urge to binge on too much food or choose heavily processed food over healthier options.

From the Stoic perspective, food cravings look a lot like propatheiai, or proto passions. These are emotions, reactions, and desires we experience involuntarily and without thought. You might look at an attractive person and experience lust, or jump if someone lunges out of a dark corner and yells, “boo!”

But these automatic reactions don’t say anything about our character. What bubbles up in the mind is not us.

Just because we feel a desire to binge or eat more chocolate than we consider wise doesn’t mean we’re immoderate or failing to live up to our values. It’s what we do after we’ve noticed the desire that matters.

So what do we do with the urge once we’ve noticed it?

Craving Responses Put To The Test:

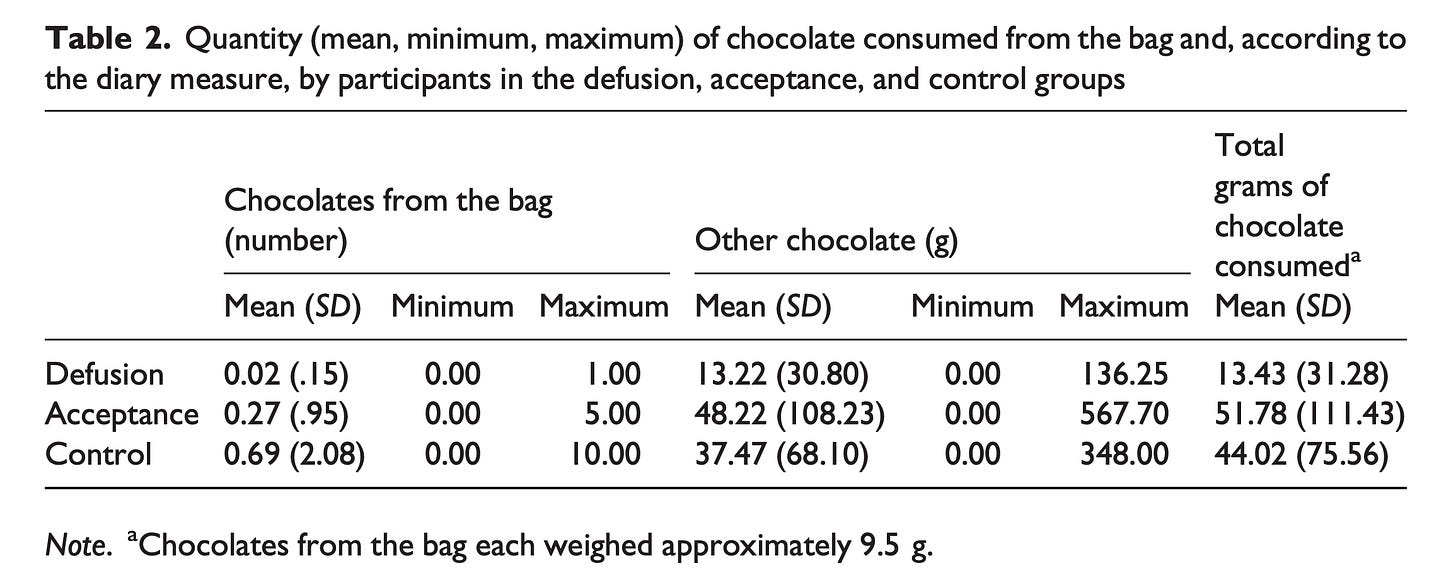

Researchers asked 137 chocolate lovers prone to overeating to carry around a bag of chocolate for five days. They were split into three groups:

Cognitive Defusion: One group was asked to practice seeing their thoughts and cravings as separate from themselves and not statements of fact or reality. They were told to see themselves as the driver of a bus and their thoughts as passengers. Their passengers might want chocolate, but participants had to decide if it was a good idea to pull the bus over and give in to the passengers.

Acceptance: One group was asked to fully accept their chocolate cravings and urges, and yet “surf” the desires and not give in to them.

Control: The control group was asked to practice a muscle relaxation technique.

Results: 27% of the defusion group ate chocolate over the course of five days vs. 45% among the acceptance group and 45% among the control group. Among those who did eat chocolate, mean consumption was lowest in the defusion group (13.43 grams) compared to the acceptance group (51.78 grams), and the control group (44.02 grams).

The effective cognitive defusion strategy lines up with the Stoic approach to propatheiai (urges and gut reactions to things). Stoics don’t just accept these impressions/desires as reality or truth and automatically give in, but keep them at arm’s length and try to see them for what they are — (perhaps just unruly passengers on our bus.)

“Don’t let the force of the impression when first it hits you knock you off your feet,” Epictetus told his students. “just say to it ‘hold on a moment; let me see who you are and what you represent. Let me put you to the test.5’

Gaslighting yourself about the food desire (I don’t really want it) or substituting another “better desire” for it without dealing with the underly reality of the thing isn’t likely to work. A well-studied mindfulness approach called cognitive restructuring tries this. Cognitive restructuring might look like realizing that you want some cake, but instead telling yourself “I don’t really want cake. I want an apple.”

When the same chocolate experiment was repeated pitting defusion and restructuring against each other, the defusion group had more than 3 times the odds of staying “chocolate abstinent”6.

Step Three: The Long Game

Once a Stoic notices a food craving, and then reframes their urge as something separate from themselves, they interrogate the desire to see how it lines up with the values they hold.

“First tell yourself what kind of person you want to be,” Epictetus told his students, “and then act accordingly in all that you do.”

If meeting a desire is in a Stoic’s control, and won’t harm their character, they’ll consider it. If it’s outside their control or will harm their character, they’ll do their best to reject it.

This, in my view, is key, and the most critical element for keeping my extra weight off all these years. Most people already have effective tactics/skills for weight loss, or can easily learn some. Numerous studies show that people are capable of losing lots of weight via a variety of methods. Short-term dieting is relatively easy.

But across hundreds of studies, participants regain about a third of their lost weight within the first year, and by 5 years more than half of participants have returned to or exceeded their baseline weight7.

I think the only thing that will lead to long-term weight maintenance is acting in accord with deeply-held values/virtue/character. Many have the how part down. It’s a deeply-inculcated why that’s lacking.

Putting Virtue to the Test

This element of Stoicism has never been researched to my knowledge, but there’s a studied intervention that offers an approximation.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Unlike traditional approaches to weight loss, which sets losing weight as the primary goal, ACT’s primary goal is helping people live in alignment with their values, much like Stoicism asks us to live in accordance with virtue. It recognizes that living more in alignment with our eating/health values may cause weight loss, but this is outside of our total control, and not the primary goal. The goal is to act well regarding food, to the extent that we can.

ACT tries to get people to take values-based action in the presence of unwanted thoughts, cravings, and bodily sensations. Several elements of ACT do not line up with Stoicism, but these are beyond the scope of this article.

A 2020 systematic review and network meta-analysis of overweight and obese adults showed that ACT had the most consistent effects on improving weight loss beyond 18 months when compared to mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy (MBCT), compassion-focused therapy (CFT), and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)8.

However, all the tested interventions injected some WHY into the weight loss equation, and did better than studies that just tried to give people the HOW.

My reading of the literature is that ACT needs more study before we can draw firm conclusions, but it looks promising and can serve as a demonstration of the virtue/character based litmus test for decisions Stoicism utilizes.

So I think a strong argument can be made that several elements of Stoic practice can help us with weight loss and weight maintenance, based on the scientific literature.

As Seneca said, “Hold fast, then, to this sound and wholesome rule of life; that you indulge the body only so far as is needful for good health…Eat merely to relieve your hunger; drink merely to quench your thirst…And reflect that nothing except the soul is worthy of wonder; for to the soul, if it be great, naught is great.9”

Blass EM, Et al. On the road to obesity: Television viewing increases intake of high-density foods. Physiol Behav. 2006;88(4-5):597-604. Link.

Hetherington, M. Et al. Situational effects on meal intake: A comparison of eating alone and eating with others. Physiol Behav. 2006;88(4-5):498-505.) Link.

Seguias, L. Et al. The effect of mindful eating on subsequent intake of a high calorie snack. Appetite. 2018 Feb 1;121:93-100. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.041. Epub 2017 Nov 10. Link.

Carriere, K. Mindfulness-based interventions for weight loss: a systemic review and meta-analysis, 2018 Feb;19(2):164-177. doi: 10.1111/obr.12623.Epub 2017 Oct 27. Link.

Epictetus, Discourses 2.17)

Moffitt, R, et al. A comparison of cognitive restructuring and cognitive defusion as strategies for resisting a craved food. Psychol Health. 2012;27 Suppl 2:74-90. Link.

Butryn, ML. Et al. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2011;34(4):841–859. Link.

Lawlor, E. Et al. Third-wave cognitive behavior therapies for weight management: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2020 Jul;21(7):e13013. doi: 10.1111/obr.13013.Epub 2020 Mar 17. Link.

Seneca. Moral Letters, On the Philosopher’s Seclusion (VIII, 5 )

Stoicism works! I am on hour 25 of a 72 hour fast right now. Down 47 lbs thus far!