The Only Game Worth Playing

Walking two paths to the good life

Why does Quintin Tarantino rewatch movies he made years ago?

He has a refreshingly joyous answer:

“I love my movies! I’m making them for me. Everybody else is invited.”

It’s an answer few directors could give. In an age of movies churned out by committee for maximum profitability, Tarantino pleases himself, not the audience. That his work happens to also please a devoted fanbase eager to buy tickets is beside the point, a pleasant side effect of pleasing himself.

But even these by-product profits have generated a windfall. Tarantino is rich enough to retire, so why does he slave away, cranking out masterpieces?

There’s only one answer: He’s playing for himself, and he chose the right game.

This seems incredibly lofty for us mortals trying to pay our bills. But the philosopher Aristotle explained a framework for moving in Tarantino’s direction.

There Are Only Two Actions:

“Happiness then, is found to be something perfect and self-sufficient, being the end to which our actions are directed.” — Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics.

In Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle separates human action into two buckets:

What we do for money, prestige, power, or another external achievement. This is the utility game.

What we do because it’s good and rewarding in and of itself, with no external reward required to make it worthwhile. This is the virtue game.

The first is a means to an end. The second goes on forever because it always justifies another round of play. It’s hard to retire completely from the virtue game because it means no longer doing what’s right and resonant.

Aristotle’s utility bucket dominates society. We don’t want to starve. We want shelter for our families. We want a comfortable retirement.

So we take utilitarian actions — some of which are objectively bad — largely under compulsion.

Master the Wrong Game at Your Peril

Masters of the utility game are a dime a dozen. Many aren’t even aware the virtue game exists, or can’t pull themself from the dopamine pump of winning money and praise long enough to explore it.

There is no greater example of ignorance of the virtue game than the FIRE dude who mastered the utility game, became rich, and descended into a prison of shallow pleasures that his own wife found pathetic.

All he knows is winning money, and the consequences aren’t pretty. Amid his wealthy freedom, he’s a slave.

Signing Up for the Virtue Game:

I define the virtue game: Giving careful consideration to what is right and resonant and acting on it — to the degree you can — without the demand that it gets you anything beyond the satisfaction of doing it.

“So very idealistic, Andrew,” I hear you saying. “But I’ve got bills to pay.”

As do I. But we can move toward this ideal in two ways, and can walk both paths at the same time.

1) Subvert With Virtue:

Virtue makes us happy, but it can also be subversive. It can take a utilitarian game played for money or power and stealthily drag it into the opposing camp with no one the wiser.

I would not choose to sweep floors for money. But if that’s what it took to live, could I clean virtuously? Could I move the broom and empty the bins in line with wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation/discipline?

I suspect I could. I suspect someone could clean rooms like Michaelangelo painted ceilings, though I might fall short. And what’s the alternative? To live in rage-filled resentment of a world that requires me to sweep floors? Or maybe I just phone it in and spend forty hours a week as a husk of what I am.

Virtue has a way of ennobling the dross, but also in elevating us beyond the status quo. A master cleaner may find another rung on the utilitarian totem poll opens up as their devotion and skill is recognized, and they can bring virtue to that rung too.

Accountant? Restaurant prep cook? Warehouse laborer? These roles too can be executed with virtue.

As we rise and grow and get better at bringing virtue to every little thing, we may find that one day we’re playing the game for its own sake, and the money is just a pleasant byproduct. This is the roundabout way to the virtue game.

Money doesn’t make a thing vicious. Sometimes, money is just the game you bring virtue to. Modern Americans love to hate billionaires, but some billionaires care nothing for money, and only want to play the virtue game.

The recently deceased Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway fame was one such man. Read his excellent essays to get a sense of how he made lots of money playing the game well.

2) Play a Game on Your Terms

“Work is not a good. So what is? Not minding the work. For that reason, I am inclined to fault those who expend great effort over worthless things. On the other hand, when people strive toward honorable goals, I give them my approval, and all the more when they apply themselves strenuously and do not let themselves be defeated or thwarted. I cry, “Better so! Rise to the occasion! Take a deep breath, and climb that hill—at one bound, if you can do it!”

— Seneca, Letter 31

While you pay your bills with an increasingly subverted utility game, you can begin doing things for their own sake, perhaps during your nightly void. You know what these are. They call to you. They strike you as the right thing. They’re resonant.

Probably, you don’t know exactly what this looks like. Maybe you don’t yet have the complete skillset. But you’re being called. So start. Start fumbling toward the virtue game as best you can. Try different things. Fail. Reorient, and try again. If it seems right, calls to you, and is in line with virtue, then follow that thread.

If you’re really doing this for yourself, and because you want to please yourself, you’ll keep improving because that too is pleasing and virtuous.

You’re Reading a Virtue Game:

Socratic State of Mind is my virtue game. This essay is part of it.

Maybe 90% of my audience got bored and stopped reading before this sentence. Maybe you’re still on board, and I’m pumped if you are.

But I’m walking the wire of serving you as I serve myself. I’m clarifying my thinking through writing, nudging the world in a good direction, and doing what strikes me as resonant and virtuous. I want to be like Tarantino — able to read my essays and think, not bad! I like that!

I talk about obscure schools of ancient philosophy here. I’m not expecting mass appeal. Who gives a shit about philosophy besides me?

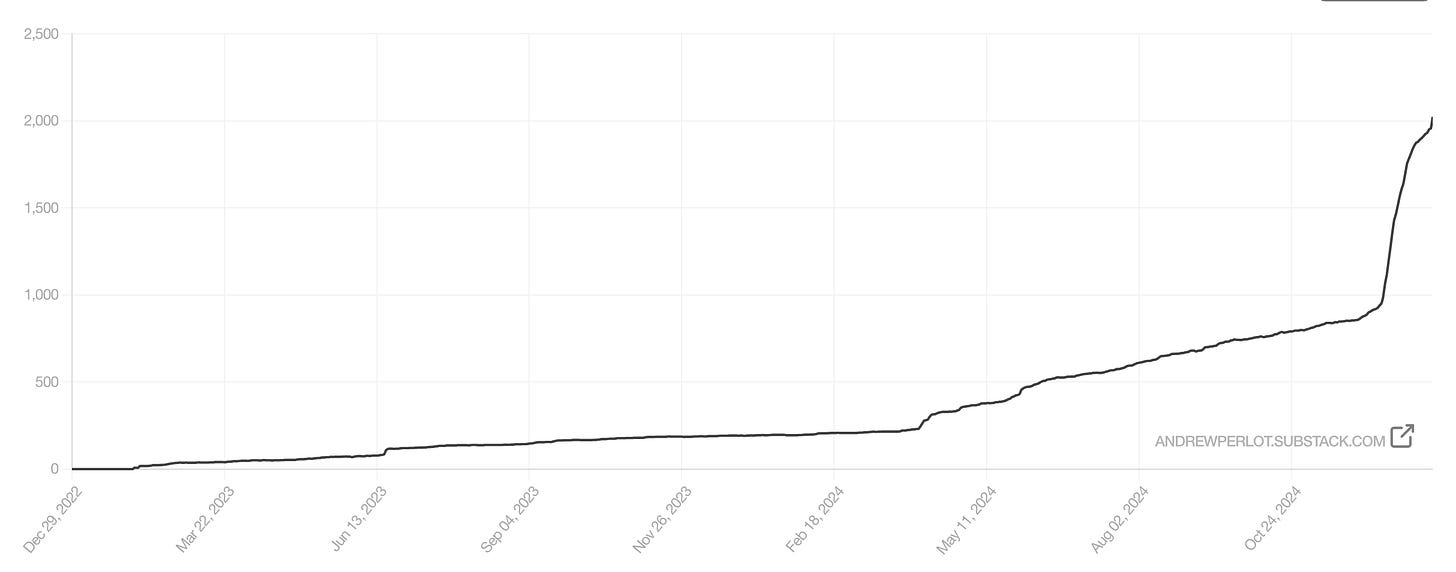

Well hilariously, it turns out that people do — at least 2,024 at this moment, if my free subscriber count is any indication.

When I started almost two year ago, I sucked. My rate of growth was abysmal. But I kept chasing the resonant and the virtuous, trying to improve. I was doing it for me, by my standards. Then a funny thing happened — more and more people got interested. The more I leaned into the resonant and virtuous, the more I pleased myself by improvement, the more people liked it.

Twenty of you wonderful people like what I do enough to pay me in appreciation. That’s amazing! Maybe one day I can do this or something adjacent full-time. That would be great, and feel free to contribute!

Maybe I’ll eventually charge for more stuff. Or sell courses. Or whatever. Maybe I’ll be like Tarantino with those ticket sales.

But let’s be real. If I do this primarily to win your money, we both lose. If I change course to please you, we lose. If I start contorting away from what I know is right in my head and heart, we all lose.

The moment I try to please you at the cost of me, something goes haywire. I can’t serve you if the cost is what’s right and resonant.

The utility game? Yes, I do that elsewhere, with as much virtue as I can muster. But here? This is where I play the virtue game.

I suspect that between these two sallys into the good life, I’m going to find what I’m looking for. In a way, I already have.

I hope you do too.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you enjoyed this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

As a 25 year veteran in the mortgage industry, I had an epiphany about two years ago, arguably one of the most difficult times in our industry. The epiphany was how much I’ve enjoyed having financial conversations with people looking to buy or refinance. The result? Yes it was more business, but more importantly i’ve really developed a love affair with the knowledge I can dispense, and in being helpful. In fact, I’ve enjoyed helping so much more than any dollar amount made. I believe this epiphany has struck a cord deep within me, making it so that most of my days are filled with joy, regardless of whether I’ve brought in a mortgage loan or not.

Thank you for sharing your joy with us!!

Andrew, you got this. I’m with you.

Jeffrey