To the extent that the average person thinks about ancient Roman society at all, they probably envision a few rich aristocrats hoarding almost all the wealth and ruling over a destitute and exploited underclass drowning in misery.

Putting aside the slaves who owned not even themselves, average plebeians were far poorer than the most destitute people in the United States today. But that’s probably not because all the wealth was in the hands of rich patricians.

Ancient Rome looks almost egalitarian when comparing their wealth inequality to ours. The richest 1% of Americans held 32.3% of the nation’s wealth in 2021, perhaps the greatest concentration of riches in world history.

Historians and economists estimate the top 1% of Roman society controlled only 16% of the wealth1, or roughly half of the share controlled by the US’s 1% today.

Rome’s upper crust was sometimes exploitive, money hungry, and immoral, but their wealth accumulation wasn’t particularly conspicuous by today’s standards.

We don’t have enough economic data from ancient Rome to make definitive claims about why wealth was less concentrated, but we do know that Rome’s elite gave away staggering amounts of their wealth to less fortunate fellow citizens, relieving poverty, building a unique culture, and perhaps nudging the future course of world history in a positive direction.

Modern Billionaires Aren’t Particularly Generous

The names of rich philanthropists are splashed on modern hospitals, college campuses, and cultural institutions the world over, so it’s easy to get the mistaken impression that the wealthiest people are very generous.

But given the vast sums held by the 1%, their philanthropic efforts are surprisingly stingy.

The country’s 400 richest people, tracked by the Forbes 400 list, had assets of $4.5 trillion in 2021, or an average $11.25 billion per person. That’s a staggering amount of money. Yet lifetime charitable giving by these billionaires amounts to less than 1% of their net worth2.

Maybe you’ve heard about Warren Buffet’s giving pledge, where he encourages billionaires to give away at least half their wealth. Since 2010, 235 billionaires across the world have taken the pledge. Yet this amounts to only $600 billion in pledges. For perspective, the richest 1% in the United States held $41.52 trillion in assets in 2021.

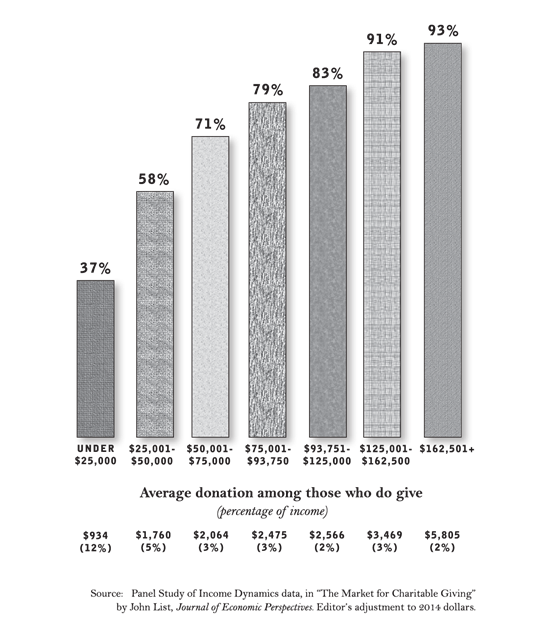

From an income perspective, those making more than $162,000 a year donate 2% of their yearly income to charity on average. The groups making less than $50,000 donate 5% or more on average3.

There’s something strange about how little our billionaires give, considering their staggering resources and the relatively modest outlay required to support a good life.

The elites of the Roman Empire, flawed as they were, make our modern billionaires look like misers.

A Roman Warren Buffet

One of our best sources on imperial Roman giving is Pliny the Younger, a rich Roman patrician, orator, and lawyer with many surviving letters and inscriptions attesting to his philanthropic work. He was comfortably within the top 1%, but not noted as particularly rich.

Here are some of the projects we know he funded4:

A large charity scheme that sent cash payments to rural families with children around Como (ancient Comum), Italy.

A new public library, bath complex, and temple in Como, with funds set aside for the long-term upkeep of these facilities.

A public temple in Tifernum Tiberinum.

Paying the salary of a teacher to instruct children in Como.

Restoring a public temple on his lands visited by surrounding farmers.

Public feasts at Tifernum and Como.

Freeing more than a hundred of his slaves and setting up a fund to care for them for life.

The commission and donation of bronze statues and other art to Como.

The estimated value of Pliny’s known philanthropy projects is 5 million sestertii5.

How much of Pliny’s wealth did this represent? A rough estimate is that his vast landholdings — the largest share of his wealth — were worth 17 million sestertii. Most of this was income-producing farmland. He also had six or seven houses and villas scattered around Italy, and more than 500 slaves to work his land. His income from farmland and the interest-bearing loans he made may have earned him 1.2 million sestertii a year6.

If we estimate a net worth of 25 million sestertii, the 5 million sestertii we have a record of him giving away amounts to 20% of his fortune. It’s likely that he had other philanthropic projects we have no record of which would have boosted this figure.

Pliny Was One Of Many

We don’t know if Pliny was an imperial Warren Buffet — donating a vastly larger share of his wealth than the average patrician — but it was not unusual for Roman elites to give away massive chunks of their net worth, well above the <1% average of the Forbes 400 list. This is attested to by numerous surviving letters and inscriptions.

To name a few: An unnamed donor gave Aspendos 8 million sestertii. A man named Crinas left Massilia 10 million sestertii in his will. Herodes Atticus spent 16 million sestertii building an aqueduct for Alexandreia Troas.

Herodes Atticus was incredibly wealthy, and perhaps the richest man of his era, but even if he had as much money as Crassus, the richest man during the late Republic with a fortune worth 200 million sestertii, he’d still have spent 8% of his net worth with this one aqueduct.

One inscription from Xanthos-Letoon in Asia Minor memorializes an unknown donor whose funds provided for, “the education and the nurture of all the children of the citizens, having personally undertaken the task for sixteen years, and thereafter having assigned to the city properties and money with preliminary funds for one year, so that from the income his charity may be preserved in perpetuity7.

Some of the greatest art ever produced was created because of the patronage of Rome’s 1%. In an age before writing was a viable career path, Gaius Cilnius Maecenas gave generous cash handouts and housing to Horace and Virgil, who went on to produce great works like The Satires and The Aeneid which are still read today.

North Africa: Land Of Philanthropy

We have lots of evidence for philanthropic giving from Rome’s North African provinces, which a historian noted was “a constant feature of the activities of the urban upper class8.”

What were these rich men doing for the rest of Roman society?

Creating many private schemes by which wheat, wine, wine, olive oil, and other foods were distributed to all classes of society, and other schemes which gave cash payments to parents with children, particularly rural children. These involved hundreds or thousands of citizens.

Regular public banquets.

Financing festivals, athletic contests, plays, and other cultural activities.

Constructing public health amenities such as fountains, sewers, bathhouses, and aqueducts.

Building roads and other infrastructure.

Creating public libraries and otherwise improving educational opportunities.

Sponsoring amphitheater games and gladiatorial fights.

Building and renovating theaters.

Donations of many statues, including some that were made of silver and highly valuable.

Various other artistic sponsorships and donations.

Rich patricians also headed vast patronage networks, and provide their poorer clients with financial and legal aid to maintain a base of support. This largess included a daily gift of food or money known as sportula.

What Rich Romans Left Behind

Taken all together, we’re left with a record of vast private philanthropic projects touching all levels of Roman society. They may have collectively exceeded welfare and non-military infrastructure spending of the imperial government, at least outside of Italy where emperors liked to splash their largess.

The giving was on a grand scale, and amounted to one of the largest philanthropic transfers of wealth between private citizens in history.

Although this giving benefited the destitute, a tremendous amount was spread to what might be considered the “working poor,” “middle class,” “barely rich.”

Even a thousand years after the western empire collapsed, the detritus of private building and artistic patronage was so impressive that it helped inspired the Renaissance and launch a new golden age.

One historian framed it this way: “In the least of the Empire's cities, whether Latin or Greek or even Celtic or Syriac, perhaps the majority of public buildings now explored by archaeologists and visited by thousands of tourists every year were built by local notables who bore the expense out of their own pockets. These same men paid for the public spectacles staged each year to the delight of the populace... Such endowments were even more common in Rome than in the United States today, with the difference that in Rome the gifts of the wealthy were almost exclusively intended to embellish the city…”9

But the real question is why Rome’s elite chose to give away so much of their wealth and create this incredible legacy. What lessons we can take from this interesting phenomenon, and how can we put these ideas to work in the modern world?

I address these questions in this essay.

Scheidel, W., & Friesen, S. J. (2009). The Size of the Economy and the Distribution of Income in the Roman Empire. Journal of Roman Studies, 99, 61. doi:10.3815/007543509789745223. Link.

Charity Round Table. Statistics on U.S. Generosity.

Duncan-Jones, R. (1965). The Finances of the Younger Pliny. Papers of the British School at Rome, 33, 177–188. doi:10.1017/s0068246200007376 Link.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Jones, C. P. (1989). Eastern Alimenta and an Inscription of Attaleia. The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 109, 189–191. doi:10.2307/632050. Link.