They sounded like cartoon villains in their underground bunker.

“Would it not be wondrous,” asked the Japanese General Korechika Anami, “for this whole nation to be destroyed like a beautiful flower?” He was speaking of his own nation’s destruction.

On August 6th, 1945, Japan’s Supreme Council for the Direction of the War — to whom Anami was speaking — had known for over a year that it couldn’t beat the United States. Their country was in ruins and their navy was at the bottom of the sea. They were short on fuel, ammunition, and food.

But that didn’t mean they were going to surrender.

They must now “lure” the Americans ashore, said Anami, the war minister. His officers were arming civilians with bamboo spears and teaching them to strap on explosives and dive under American tanks. Anami called for a great final battle on Japanese soil — as demanded by national honor and that of the living and the dead.

Then the atomic bombs fell.

Within 48 hours the emperor overruled his councilors and demanded unconditional surrender.

The American public was ecstatic. Huge crowds swarmed Washington, celebrating in the streets. US War planners estimated an invasion of Japan would cost at least 250,000 American lives. Some expected 2-3 million Allied casualties. The public knew what they’d been saved from.

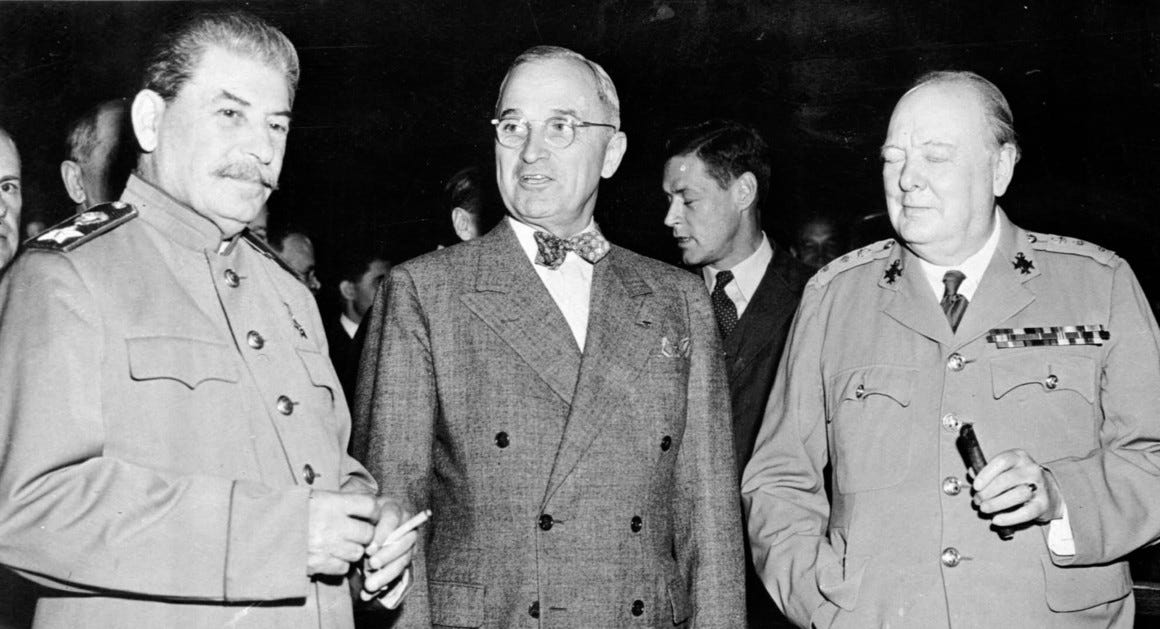

At the White House, President Harry Truman was sanguine. He’d dreaded needing to use a third bomb; the thought of wiping another city off the map was too horrible to contemplate, he said. He hated the idea of killing “all those kids1.”

Yet he’d ordered the bombing and showed little remorse later. If pressed, he might have said he chose the lesser evil, but that’s not how he explored the issue internally.

A Stoic-Influenced President

Truman had an uncanny ability to navigate moral quagmires.

We might Monday morning quarterback his choices, but he made momentous decisions that didn’t haunt him in old age. Most remain defensible.

His approach had several things in common with the Stoics. He had a heavily underlined copy of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, in which he sometimes scribbled commentary and disagreements with the long-dead Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher.

“He was one of the great ones,” Truman said of Marcus. "He said the four greatest virtues are moderation, wisdom, justice, and fortitude, and if a man is able to cultivate those, that's all he needs to live a happy and successful life. That's the way I look at it anyway…2"

Scattered through written testimony by his staff and cabinet, we see Truman repeatedly refusing to take actions that would lead to good outcomes if they meant committing an injustice.

When Truman pushed to establish the state of Israel, Secretary of Defense James Forrestal warned him his support would turn the Arabs against him and cost him access to the Arab oil needed to fend off the Soviets.

President Truman replied that he wouldn’t handle the situation, “from the standpoint of bringing in oil, but from the standpoint of what is right.3”

Stoic Evil

The Stoics didn’t believe in choosing “the lesser evil.” They didn’t even believe evil exists as we typically frame it. Instead, evil exists only inside us when we fail to make virtuous choices.

Would you kill an innocent person to save a greater number by pulling a switch and rerouting an out-of-control trolley? Stoics balk at this so-called “Trolley Problem,” and other impractical thought experiments.

Stoics know choices frequently lead to unexpected outcomes. The trolley victims might be rescued by an unseen bystander, for instance, or an earthquake might swallow the whole city. Many unexpected things might interfere with intentions.

So Stoics aim for ends that seem good, but don’t use theoretical outcomes as litmus tests. If actions require specific outcomes to “become good”, they’re not good.

But if the choice doesn’t contradict virtue, the Stoic chooses the lesser evil — their preference.

Stoics use the four cardinal virtues as a compass:

Practical wisdom is seeing clearly and knowing what is good and bad (how it affects our character).

Courage is doing the right thing, regardless of other people’s opinions and what we’ll have to endure.

Justice is being fair to others and the wider world.

Temperance demands we don’t overdo or underdo anything.

With this framework, hard decisions become malleable.

Truman vs The Machine

Truman’s early electoral victories depended on support from the “Pendergast organization,” a mob-controlled political machine with a stranglehold over Missouri’s elections. Almost no one won public office in western Missouri without Pendergast support, and corrupt Pendergast politicians stole from public coffers through kickbacks and bribery.

When Truman was elected judge of his county (an administrative rather than legal role), he had big plans to upgrade the degraded public roads and buildings. He traveled the county, lobbying residents to accept a tax for the upgrades.

After voters approved it, Truman was called before Tom Penderghast, the head of the machine, who had angry contractors waiting with him4.

“These boys tell me that you won’t give them contracts,” Pendergast said.

“They can get them if they are low bidders,” Truman answered, “but they won’t get paid for them unless they come up to specifications.”

Pendergast was furious; he got a cut from the contractors and wanted his cronies to win the bids. But Truman wouldn’t give in. After the contractors left, Pendergast told Truman to do as he pleased, but he had the other two county judges in his pocket and could outvote him.

Truman couldn’t completely stop the looting of public money. At one point he holed up in a Kansas City hotel and started journaling to get his thinking straight.

“I had to let a former saloonkeeper and murderer, a friend of the Boss’s, steal about $10,000 from the general revenues of the county to satisfy my ideal associate and keep the crooks from getting a million or more out of the bond issue,” Truman scrawled. “Was I right or did I compound a felony? I don’t know. . . . Anyway I’ve got the $6,500,000 worth of roads on the ground and at a figure that makes the crooks tear their hair. The hospital is up at less cost than any similar institution…”

As he wrote, he worked out his thinking. “I wonder if I did the right thing…to satisfy the political powers and save $3,500,000. I believe I did do right. Anyway I’m not a partner of any of them and I’ll go out poorer in every way than I came into office.5”

He sounds like Marcus Aurelius, who wrote, “No one can implicate me in ugliness6.”

Truman stayed honest. He was always broke and certainly didn’t loot the public coffers. He later championed anti-corruption and anti-waste initiatives that saved US taxpayers billions.

But were his actions virtuous? This is where wisdom comes in, which involves our ability to see clearly.

There is no external evil or good in the Stoic sense, only poor reasoning. Stoic Ethics aren’t relativistic, but they are situational. Circumstances always dictate the answers to moral questions. Wisdom and virtue helps us see clearly enough to understand what to do.

If Truman refused to run for office with Pendergast support, he wouldn’t have enacted his infrastructure program, which he thought the county needed. Alternatives to Truman would probably be worse.

Was it virtuous to stay silent about the theft? Truman thought speaking up would cause a public scandal and scuttled the valuable project.

People will square this differently. Some will see Truman as a weak-willed hypocrite like Seneca. But Truman eventually came to think his silence could be squared with virtue, perhaps seeing the theft as a cost of doing good.

He paved hundreds of roads and built multiple buildings. The work was completed early and under budget, and the public and press praised the results.

We’re reminded of what Marcus Aurelius told himself: “...don’t go expecting Plato’s Republic; be satisfied with even the smallest progress, and treat the outcome of it all as unimportant.”

Reasoning With Virtue About A Bomb

Dropping atomic bombs on Japan is often seen as an evil. Whatever your stance, Truman hoped the bombs would save lives — Japanese and American. They probably did.

Japan was already being bombed conventionally to devastating effect. The Japanese built military complexes and munition factories in the middle of dense wooden neighborhoods; it was impossible to destroy them without killing civilians. By March of 1945, tens of thousands of Japanese people were dying in the nightly bombing raids. Millions were on the brink of famine.

On March 9, 100,000 civilians died in a single raid on Tokyo. Dozens of such raids occurred, but the Japanese seemed no closer to surrender. Men like War Minister Anami insisted that Japan fight to the last. America would have to invade.

The earlier American invasion of Okinawa — a fairly small island — led military officials to assume losses would be horrendous.

On Okinawa, 12,500 Americans died and 38,000 were wounded. Around 105,000 Japanese soldiers died. More tragically, the Japanese convinced the Okinawan civilians that Americans would rape and torture them. Many committed suicide; an estimated 150,000 civilians died.

Extrapolating these losses to the Japanese home islands, a similar conquest would kill millions of Japanese civilians and soldiers. That is, if starvation didn’t kill them first.

There was no “better,” alternative to the atomic bombs. Restricting the military to conventional means would mean more slaughter. The prospect of another year of war by these means (a widespread American estimate for victory) was sickening to all who knew the reality.

On the other hand, the Japanese death toll from two atomic bombs was 226,000. This was a fraction of the most optimistic estimate for Japanese casualties in an invasion.

The Empire of Japan preferred death to surrender. Without surrender, the Allies couldn’t plant a saner form of government on the islands. They also couldn’t bring in food and medicine to keep Japanese civilians alive. Something was needed to shock the Japanese from their complacency, and the bombs worked.

Such math seems crass. It’s a crude approximation of suffering, and doesn’t account for the nuclear arms race that followed. Much ink could be spilled on whether we can ever do justice with better bombs.

But Truman’s choice was reasonable based on what he knew, and it likely drove an early Japanese surrender. It was an exercise of reason, and aligned with virtue as Truman saw it, which the ancient Stoics would approve of.

We don’t know what Marcus would say about atomic bombs, but he has advice for all of us choosing between two evils:

“Labor not as one who is wretched, nor yet as one who would be pitied or admired; but direct your will to one thing only: to act or not to act as social reason requires.” — Marcus Aurelius

Truman’s thoughts on Marcus Aurelius are taken from Merle Miller’s Plain Speaking.

Wallace, Henry. The Price of Vision: The Diary of Henry A. Wallace. Pg 606.

Truman’s quotes here are sourced from his Periwick Hotel writing.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 2.1.

Good points. I don’t believe the Stoics go for hypotheticals when they amount to many. You give a good example with: “Would you kill an innocent person to save a greater number by pulling a switch and rerouting an out-of-control trolley? Stoics balk at this so-called ‘Trolley Problem,’ and other impractical thought experiments.” If we get bogged with the “if”s, and lose sight of justice and virtue in front of us, we start to over-control the situation. As far as: “The Empire of Japan preferred death to surrender…Something was needed to shock the Japanese from their complacency, and the bombs worked.” Surrender was achieved because the fighting, or the war, was over the moment the bombs detonated—unilaterally. Yes, they never would have surrendered while fighting, even if it cost the Japanese millions of their own lives, but that’s because they were fighting (and killing) Americans. I am not sure this was a Stoic decision, or a Stoic “fight,” as far as the “cosmopolis” is concerned. A weapon of mass destruction dismantles the game of war. Nevertheless, it was the best decision for the President of the United States, representing Americans, to prevent hundreds of thousands of Americans from being killed. But not necessarily a Stoic decision.

As far as I know, Japan had no own energy resources for its growing industry but imported coal and oil. Both were subjected to a total embargo. Japanese retaliated in Pearl Harbor, but their approach was know well in advance to the US military and the big, essential vessels were removed in time...

The resulting images and casualties were the needed "trigger" to convince the populace of the events that followed suit.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, "gifted" with an uranium and a plutonium bomb were just a "test case" for curious, highly narcissistic creatures to gather new radiological data about its effects on hard and soft targets.

Despicable from top to bottom, current events in the Near East show that nothing has changed.

It's all about power and greed ...