The world’s leading men found George Washington baffling.

When the American general won the War of Independence after a long and brutal fight, they assumed he’d do what they’d do — exploit his immense popularity and loyal troops to cling to power and mold the United States as he thought best.

Great Britain’s King, George III, doubted rumors that Washington would disband his army and return to farming, echoing the reaction of leaders around the world. If Washington did, the king insisted, “He will be the greatest man in the world.1”

But Washington did resign and return to his farm. The move was so surprising because he discarded the era’s leadership playbook, instead drawing on one that was two millennia out of date.

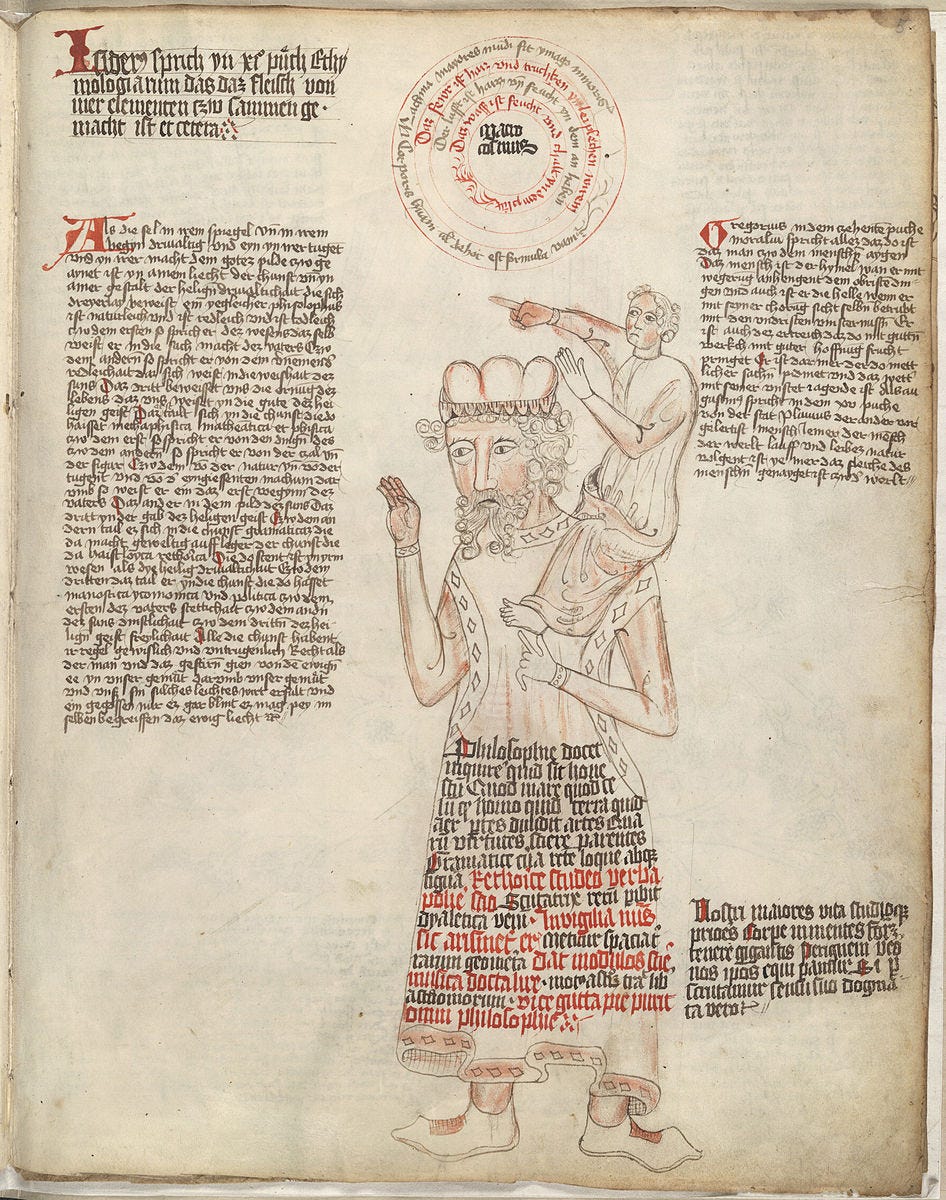

Washington embraced the trend we see in Colonial America, Renaissance Italy, multiple eras of Chinese and Egyptian civilization, and other periods by building new heights atop the ruined edifice of past accomplishments2.

Although not classically educated, Washington was steeped in the colonial idealization of classical antiquity. He knew the story of Cincinnatus, a 5th century B.C. Roman general who’d twice been elected dictator (a legal Roman office) during military emergencies. Cincinnatus quickly dealt with those crises and resigned long before his six-month terms ended. By returning to his plow, he turned down the opportunity to milk the office for all it was worth, earning the respect of fellow citizens.

Washington’s actions echoed this ancient Roman ideal, and had the same effect on Americans and observers around the world.

“You have often heard him compared to Cincinnatus," the French traveler Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville wrote after visiting George Washington on his farm in 1788. "The comparison is doubtless just. The celebrated General is nothing more at present than a good farmer, constantly occupied in the care of his farm and the improvement of cultivation.3"

Washington further cemented the comparison by refusing to run for a third term as president nine years later. By making room for new blood, he began a centuries-long tradition of peaceful power transfers. The survival of the young nation may well have depended on the precedent.

Leaders like George III couldn’t wrap their minds around Washington because of their, “inability, throughout the Revolutionary conflict, to comprehend the enormous emotional power which classical republican ideals wielded over American minds,” historian Carl Richards tells us4.

Today, we suffer not only as a civilization but as individuals because we’ve lost the habit of emulating premodern heroes and the virtues they embodied.

Without them, we’re marooned in the present, thrashing about in the water and unable to find remnants of the past to cling to. When we willfully avert our eyes from the grandest ruins protruding from the surf, we can’t build something better atop them.

The Curse of Being Stuck In The Present

A bit of dialogue in Christopher Nolan’s 2014 epic “Interstellar,” speaks to the problem of being overly focused on the ideas of the present.

The main character, played by Matthew McConaughey, is a former NASA pilot forced into farming by the economic, environmental, and political decline of Earth and human civilization.

His daughter’s teacher informs McConaughey that school textbooks now contain “the truth,” that NASA’s Apollo missions were just brilliant hoaxes produced to lure the Soviets into a space race and bankrupt them. The teacher believes this herself. But she explains why it’s important her students do too: they need lowered expectations so the “excesses and waste” of the past are not repeated. Her students need to dream about farming, not building rockets and fancy machines.

Whatever the environmental merits of lowered aspirations, the strategy is a sound one. If you want people to aim lower, to not rock the boat, and to be content with the status quo, nothing is more effective than denying past accomplishments and denigrating anyone who’s pushed humanity forward. Stories about astronauts are dangerous if you want your people to keep busy shucking corn.

Aristotle recognized this. “The society that loses its grip on the past is in danger,” he said, “for it produces men who know nothing but the present, and who are not aware that life had been, and could be, different from what it is. Such men bear tyranny easily; for they have nothing with which to compare it to.”

The state of modern textbooks is debatable, but “the past was bad and its people were monsters” narrative is certainly creeping into our society, and it is slowly stripping us of aspirations to live up to.

When we look at the past and its best exemplars with disgust, we’re forced to flounder in the deeps of the here and now, which, unfortunately, are often bleak.

How The Age of Heroes Ended

Heroes are out of fashion in America. It’s hard to find many that society thinks are worth emulating.

The US founding fathers and the ancient Greeks and Romans are denigrated as oligarchic slave owners. Abraham Lincoln, who freed America’s slaves, recently had his name stripped from a San Francisco school because his Native American policies were deemed unjust. Even Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. are considered questionable in some circles.

Listening to modern critics, one gets the impression that earlier Americans were credulous rubes easily duped by historical propaganda. The message is that we, as moderns, should realize the greatest men and women of the past were horrible people who did horrible things. It’s time, they suggest, to forget our wayward past and adopt whatever ideals are in vogue right now.

But they seem to not understand that earlier Americans were quite aware of the failings of their idols. In fact, they discussed them at length and learned many lessons from them.

After the bible, the most popular book in the Thirteen Colonies and early United States — for a period of some 250 years — was Plutarch’s “Lives,” which was written in the second century A.D5.

The “Lives,” were a series of biographies of Romans and Geeks, written in sets of two. They highlight the achievements of great people, but also their follies and vices. Each set concludes with a short comparison prodding readers to decide which of the two was superior, and in what respects. The point was to nudge readers to make hard value judgments about virtue, politics, and what it means to live a good life.

Plutarch wasn’t promoting baseless hero worship, but rather fostering two skills citizens and politicians of all eras need — the ability to practice good judgment and discern a true proposition from a false one.

The book’s educational value was so highly regarded that even founding fathers who hated each other agreed on its merit. Thomas Jefferson recommended it in numerous surviving letters and made sure the University of Virginia had a copy. John Adams wrote his son to urge him to practice his Greek and Latin. “Polybius and Plutarch and Sallust as sources of Wisdom as well as Roman History, must not be forgotten,” Adams insisted.

Alexander Hamilton, who often sparred with Adams and Jefferson, loved Plutarch’s work and praised it in writing.

The book’s popularity continued into the 20th century because it served as a crash course for navigating society and human nature.

“They just don’t come any better than old Plutarch,” President Harry Truman said. “He knew more about politics than all the other writers I’ve read put together. When I was in politics, there would be times when I tried to figure somebody out, and I could always turn to Plutarch, and 9 times out of 10 I’d be able to find a parallel in there.6”

The United States Constitution is a document built to counteract human vice and utilize it for the good of the nation, which is the result of the founders’ keen understanding of vice throughout history. The founders realized virtuous men were in short supply, and to plan for them would doom the new country.

“Ambition must be made to counteract ambition,” Alexander Hamilton wrote. “...It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature?7”

Built on this firm understanding of human failings, the Constitution struck the right balance and has warded off threats from vice-ridden politicians and the pressures of the mob for 230 years.

The Right Way to Use a Hero

Praising the heroes of the past and suggesting people model themselves after them may seem juvenile, nebulous (model how?), and relevant only to the tiny fraction of humanity engaged in politics or leading businesses.

That’s not how people thought about the topic in the past.

Life frequently throws us in over our heads. Ideally, we’d have mentors with relevant experience to guide us. Most of us rarely do, so we’re left thrashing in the water, trying to stay afloat.

But we can almost always find mentors in the past, even if we’re surrounded by fools in the present. It’s a modern conceit to think our problems unprecedented. Recorded history is a testament to how little human nature has changed these past 10,000 years, and some of the best advice on our problems was penned hundreds or thousands of years ago.

I was first exposed to Marcus Aurelius — an emperor and philosopher 1,800 years in the grave — when I was in high school. I hated everything he had to say. There’s a tendency for that reaction when we learn about how the world, human nature, and virtue really work — deny and rebel; avoid and look for ways to get off the hook. I suspect that’s how many people feel when told the past has something to teach them.

But I couldn’t stop returning to Marcus’s writings because on some level I recognized he was mulling over deep truths. He eventually won me over with his calm, patient, and matter-of-fact approach to life’s problems and living the good life. Seneca and Epictetus have different vibes, and a varied willingness to tolerate fools, but their wisdom is no less valuable.

I regularly ask the facsimiles of each residing in my head — along with a half dozen other people I’ve studied thoroughly — how they’d approach my problems. Each emphasizes different things in their answers, and varies in their tolerance of my failings.

I’ve been a son, a friend, a romantic partner, an employee, and an entrepreneur, and these roles have sometimes left me struggling and wishing for guidance.

If I’d lacked these mentors of the mind, I’d navigate life like a boxer entering the ring with one arm tied behind my back — just asking to be pummeled.

When new problems pop up, it’s just a matter of turning to the right mentor, or cracking open the right book and finding a new exemplar to talk to. This is true whether we’re a street sweeper or the president of the United States, but to make use of these mentors we need to study them and understand their philosophies. How many modern people do that in the same way the founding fathers or President Truman did?

“Happy also is he who can so revere a man as to calm and regulate himself by calling him to mind!” the philosopher Seneca writes. “…Choose a master whose life, conversation, and soul-expressing face have satisfied you; picture him always to yourself as your protector or your pattern. For we must indeed have someone according to whom we may regulate our characters; you can never straighten that which is crooked unless you use a ruler.8”

Adrift in the Endless Now

But Andrew, I hear some of you saying. It’s well enough to pick guides to help us regulate our character and make good decisions, but you’ve picked wrong! Have you not heard how deplorable these people were? Marcus owned slaves. Seneca was a member of the one percent and abetted a tyrannical emperor. Victor Frankl, a psychiatrist, lobotomized patients. Martin Luther King Jr. was a philanderer. Gandhi shared his bed with naked young women, even if he never touched them. Sir Isaac Newton was a petty and vindictive jerk keen on ruining his scientific rivals. And the list goes on.

There are two good replies to this:

First, people are flawed. Few pass all the tests life throws at them. That’s always been true, and it’s certainly true now. Should we ignore the wisdom of someone who made major contributions, and who could teach us critical lessons, because they were imperfect?

Second, judging yesterday’s people by today’s standards is unfair. If someone pushes humanity forward in a single positive direction we should appreciate how hard they struggled against the constraints of the time, constraints often lifted by their efforts. Clearing one strip of the tangled brambles of human ignorance may take so much energy that there’s little left to contemplate the rest of the wilderness surrounding us on all sides. Can we blame people for not getting to all the patches of brambles in their lifetimes?

Future people will find our present benighted and morally compromised. Some of us notice ways society is falling short. Perhaps we’re even ahead of the curve, pushing things forward. But we cannot know, nor do we likely have the energy and time to address, the many ways the future will bemoan our failures.

Should we too be censored for our shortfalls in foreseeing how norms will change? Should our accomplishments be disregarded because we didn’t see ALL the ways we could have done better?

Like It or Not, We’re Stuck With the Past

Even if you think we should denigrate the heroes of the past and all they stood for, how do you plan to move forward to something better without utilizing past pioneers?

We can’t study the future, so the past gives us something to set against the present. Considering it reminds us that basic assumptions were radically different in prior eras, and therefore, that ours might be misguided.

If we want to do anything worthwhile, we need this firm foundation and the contrast of opposing ideas to challenge our own.

Sir Isaac Newton may have persecuted and denigrated contemporary rivals, but even he acknowledged what he owned the past. “If I have seen further [than others], it is by standing on the shoulders of giants,” he said. I.e. — the seminal figures who paved the way for his advances in prior centuries9.

In an era ignorant of its history and bereft of heroes, embracing the past and its ideals is a revolutionary act that may gives us an advantage and stop the myopic focus on present fads.

Modern ideas are ubiquitous. Viral social media posts and recently-published books dominate society’s mental landscape. Almost no one bothers with the ideas of the past, thinking them outdated. Yet it is these ideas that set our thinking free.

“A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his village,” C.S. Lewis wrote. “The scholar has lived in many times and is therefore…immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.10”

A good rule of thumb is the 50/50 Rule: make sure at least 50% of the ideas you take in are older than 50 years. This generally means reading old books.

When you’re stuck in life or trying to solve a problem, begin by asking — how would Plato, Filippo Brunelleschi, or Cicero have approached this?

Maybe they have nothing to offer you, but if you’re so ignorant of their worldview that you can’t even conceptualize their approach, you’re entering the ring with one arm tied behind your back. Good luck.

As Haruki Murakami said, “If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.11”

Richards, Carl. The Founders and the Classics: Greece, Rome, and the American Enlightenment. Pg 71.

The premise of Michael Bonner’s In Defense Of Civilization, which I briefly reviewed here.

Brissot de Warville, J.-P. New travels in the United States of America. Performed in 1788. Translated from the French (London, 1792), 428.

Richards, Carl. The Founders and the Classics: Greece, Rome, and the American Enlightenment. Pg 71.

Reinhold, Meyer. Classica Americana: the Greek and Roman heritage in the United States. 1984. Pg. 250.

Miller, Merle. Plain Speaking: An Oral Biography Of Harry Truman. 1973.

Hamilton, Alexander. Federalist No. 51.

Seneca. Letters on Ethics to Lucilius. Letter 11.

Newton, Isaac. "Letter from Sir Isaac Newton to Robert Hooke". 1675.

Lewis, C.S. “Learning in War-Time.” 1939.

Murakami, Haruki. Norwegian Wood. 2000.

Thank you for the reminder of Petrarch. I've been spending a lot of time recently reading and thinking about the Enlightenment. Most of my heroes are either from that age, or have consciously looked to that era for inspiration or emulation. Its almost hard to imagine what might have been had it not been for the renaissance reacquaintance with Greek and Roman thinkers.

Well said. The ancient Romans constantly reflected on the exempla offered by statesmen, soldiers, philosophers of the past; there were how-to's and how-not-to's, as human situations tend to repeat, and relationships tend to be very similar! People are still ambitious - rivalrous - treacherous - loyal or disloyal - hardworking or lazy - and there are instructive tales from which to learn.