The Baby Boomers did it. So did Gen X.

What are they guilty of?

Being horrible people, of course. Escalating housing costs, environmental catastrophe, and the decline of the United States are laid at their feet each day on social media. Case in point:

We might dismiss this as economic and historical illiteracy1, or just another example of our age’s black-and-white thinking. Nuance isn’t our strong suit, and demonization is an effective means of rallying the disaffected.

As a 40-year-old millennial, I suspect my generation will face the firing squad of opinion soon enough. It doesn’t matter that a significant chunk of us voted to support saner government policies that were mostly not enacted. Since we were alive and voting during many fiascos, a broad brush will be used to paint us — as if we are one monolithic bloc — with the errors of our time.

Billy Joel’s 1989 song, “We Didn’t Start the Fire,” now seems prescient, a baby boomer's “non mea culpa" each generation can chant in turn to defend itself from the fury of its descendants.

“We didn't start the fire

No, we didn't light it, but we tried to fight it.”

Except this firefighting is equivalent to spraying a hose at a burning building, pretending there isn’t an open gas main underneath.

The problem isn’t horrible generations, greedy individuals, or moral delusion. Today’s generations are par for the course — largely as stupid, leadable, and average as past ones.

Attributes differ between generations, but we’re all humans prone to bias and following the incentives our culture, economic system, and government lay before us. Incentives can be resisted by the strong-willed, but most people won’t put up a fight.

In the framework each generation inhabits, their initial outrage and inevitable cooption into “the system.” is economically and socially rational, and it would be more surprising if it didn’t happen.

The real question: can we change our incentives to lead to better systems and outcomes?

“Plantagenet, I will; and like thee, Nero,

Play on the lute, beholding the towns burn.”

— Shakespeare, Henry VI

If we can’t change the incentives, each generation will be furious at its predecessors for failing to right the ship, for fiddling while Rome burns. If we want something better, we need to start talking about that leaking gas main underneath so many of our fires.

I’ve already written about the incentive quagmire at the heart of our intractable problems. But can we do anything about them? What would that actually look like?

Let’s start with this: Where does the buck stop?

The Buck Never Stops

President Harry Truman was no saint, and had his biases and blind spots, but he repeatedly made morally defensible choices in incredibly hard situations.

He owned his decisions, famously proclaiming, “the buck stops here.” It seems to have been more than good political marketing. He never blamed the crime syndicate that tried to control him, the bureaucracy serving him, or an intransigent and ignorant public. He just rather refreshing claimed responsibility for his choices.

But most people aren’t Truman. Sure, they want power, but they don’t want the buck to stop with them, or to suffer negative consequences for misusing power. Even if well-intentioned, they’re blinded by the “moral hazard” of taking risks that will mostly be borne by others.

Renters trash a property, figuring that they can’t lose anything more than their deposit.

Big banks gamble with investments, knowing the federal government will bail them out because they’re “too big to fail.” Win, I win. Lose, you lose.

Politicians casually send the military to war, knowing neither they, their families, or the broader public will bear any consequences. Only the 0.38% of the U.S. population serving in the military and faceless casualties aboard will pay if they choose poorly.

No One Pays For Ruining Everyone Else

“…there is no possible risk management method that can replace skin in the game…(when) those who gain the upside resulting from actions performed under some degree of uncertainty are not the same as those who incur the downside of those same acts.”

— Nassim Taleb, The Skin In The Game Heuristic for Protection Against Tail Events

People should be rewarded for good work. It’s an effective heuristic as old as time, but insufficient for incentivizing positive-sum outcomes when risks are primarily borne by others.

When entrepreneurs take risks, they suffer consequences if they choose poorly. Over-leveraged investors are ruined when the stock market tanks. Incentives push them toward caution.

But what happens when you double down on a risk that can only backfire for others? Many chronic ills stem from this dynamic.

Take Congresspeople who pass laws favoring industry at the cost of citizens and the environment. What’s their punishment? The traditional view is that they’ll be voted from office. That rarely happens. And even after leaving office, congresspeople move on to cushy, well-paid jobs in the industries they once regulated. So there’s little downside and great upside in hurting others.

Why Trains Never Get Built

“I have no spur

To prick the sides of my intent, but only

Vaulting ambition, which o'erleaps itself

And falls on the other.”

— Macbeth, Act 1, Scene 7

America’s failure to build anything of consequence is the rule rather than the exception, but it’s a recent turn of events. A few decades ago the nation tackled big projects and got them done. In the 1930s, the massive Hoover Dam was completed two years ahead of schedule and way under budget — The modern American mind boggles.

Today, California is a political punching bag for its boondoggled high-speed rail project, which is 25 years behind schedule and $33 billion over budget. But an interesting question emerges — who’s to blame? You might target construction companies, politicians, or committees, but it’s hard to definitively say who’s responsible. Why? Because no one is responsible.

We live in a vetocracy where no one is in charge. No one can say yes, but just about everyone can say no. Even if someone can theoretically say yes, it’s to their advantage to kick the can down the road and let the interminable process play out so they don’t have to take responsibility. With any luck, it will be the next administration’s problem.

All the delays, all the nos, come from our modern idea that it’s good for everyone — no matter how self-interested or ignorant — to have a say and a chance to scream “NO!”

Instead, I’d suggest that one person should get to say yes when they’ve deemed all things in order. If they choose well, they will be greatly rewarded. If they choose poorly, they will rue the day.

Let’s talk about what that can look like in different scenarios.

Clearcutting Our Forest of Nos

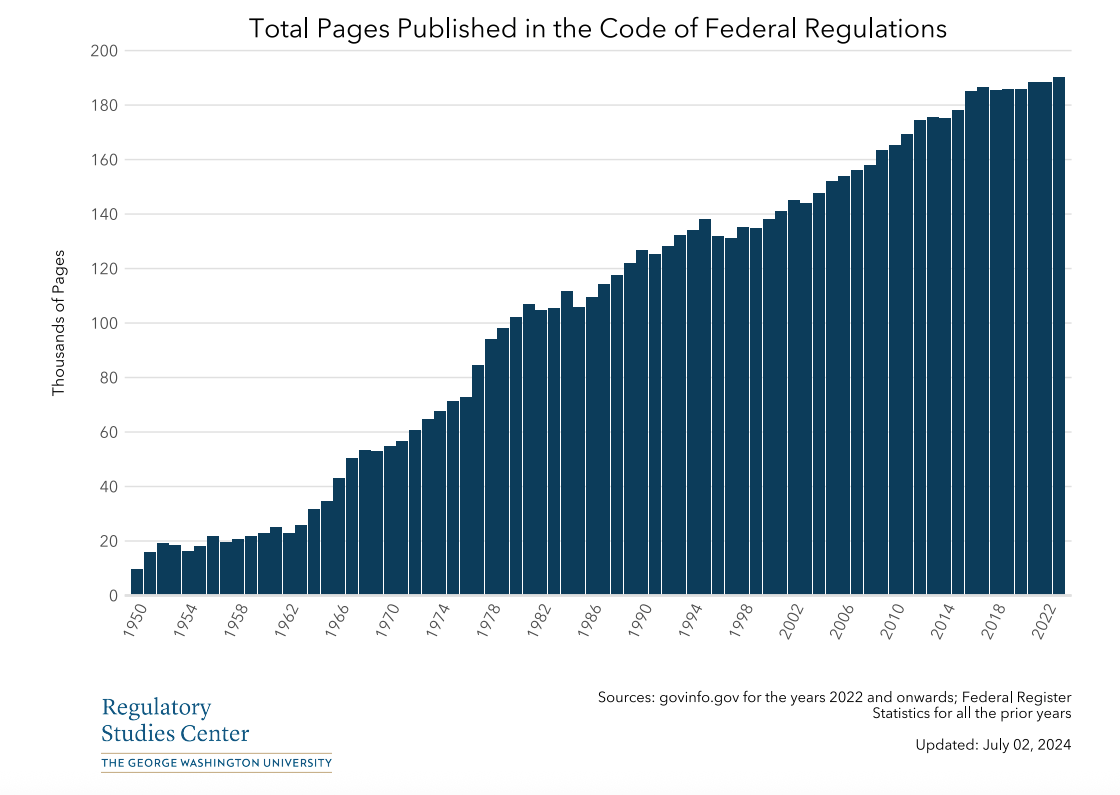

Every modern project navigates a thick forest of nos. Endless regulations and committees meddle with projects without a conception of the effects. Though well-intentioned, this thicket became virtually unnavigable over the last century.

Most or all of these regulations need to be swept away for something simpler.

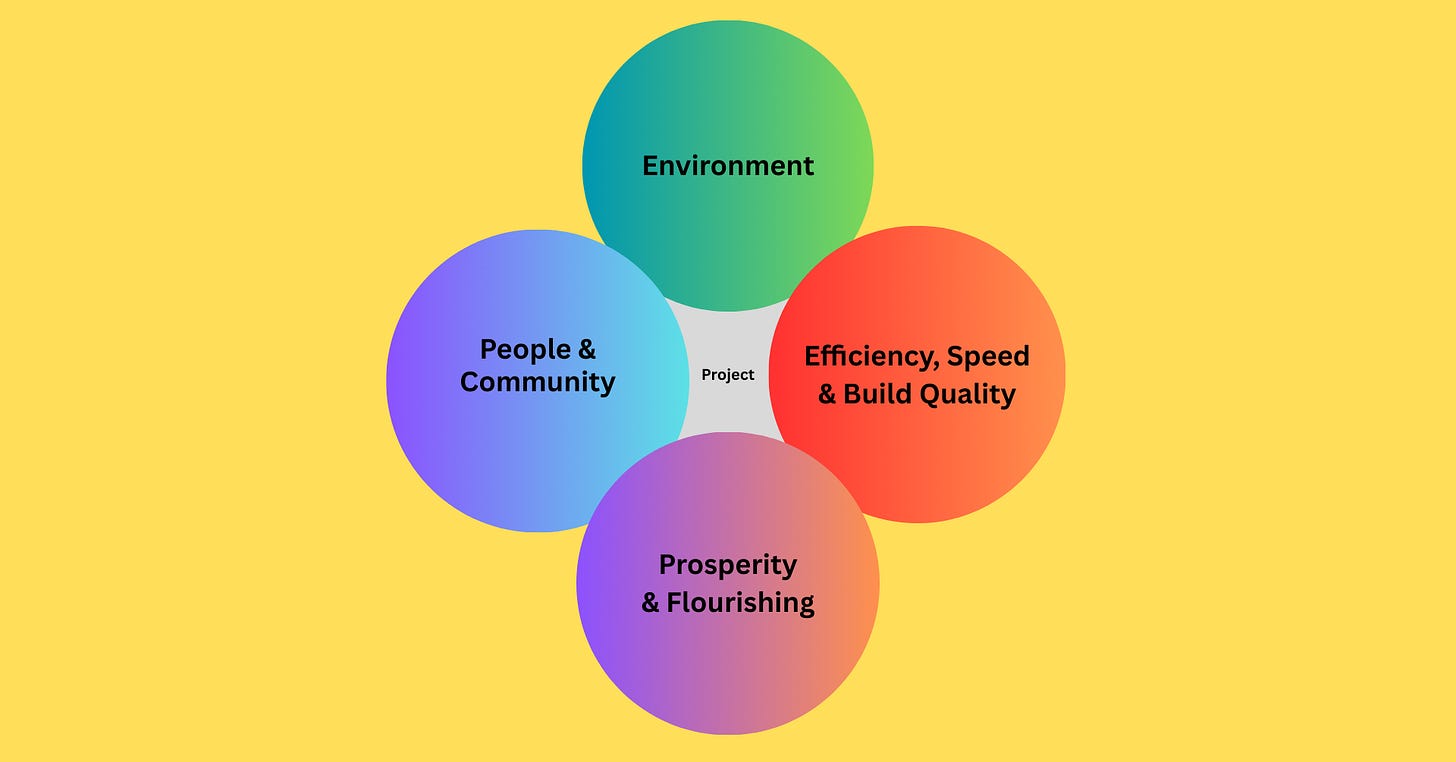

Every project must balance best practices in these things:

Environment

People & Communities

Efficiency & Speed

Prosperity & Build Quality

In a construction context, a company — with one decision maker at the head — gets to be the yes-sayer without navigating layers of bureaucratic and public approvals. They are guided by clear metrics for appropriate outcomes.

The yes-sayer would of course hire biologists, sociologists, and other experts to check their plans, since it would be too risky not to. In the event of problems, a paper trail showing due diligence might be one of the few mitigating factors that transfers a portion of the penalties onto a contractor.

Outcomes would be judged by specific, quantifiable metrics like long-term air quality and crash rates over project lifetimes. Standards would be descriptive rather than prescriptive. They would be outcome-focused but method agnostic. Did that farmer you took land from get ample compensation? Did a poor community get left holding the bag? Can wildlife migrate over the tracks? That’s what matters, not how these outcomes were achieved.

Outsized success in navigating these competing interests means financial windfalls and reputation for the yes-sayer and his company. Failure means personal monetary and legal penalties in line with the scale of the disaster. If you wipe out an endangered species and build a bridge that collapses three years after completion, you may end up financially ruined and jailed.

Projects will face a full accounting down the road, and this is a great way to reduce human cognitive bias.

This has several advantages. Currently, people in the public and private realm seek promotions and leadership roles for the wealth and prestige they bring. But in this model, that’s only a good idea if you’re confident in your ability to not mess up and balance these competing interests. There’s no escaping a failure since you signed off on it and will bear the consequences. If you have a long track record of success and your boss offers you a promotion, you might turn it down if you suspect you’ve merely been gliding in the wake of bigger fish, and will misstep when the baton is handed to you.

Fix Money Manager Incentives

The current system encourages money managers to bury volatility and risk at the tail end, delaying blow-ups till after bonuses and promotions roll in.

A better system ensures that any bonuses received for high performance from risky investments would be returned — and additional hefty fines paid — when the investments go bad in subsequent years.

In addition, money managers should always be investing a significant part of their wealth in the schemes they cook up. This causes them to take more moderate risks.

Fix Military Interventions

Who bears responsibility for the disastrous wars our nation has fought for decades? Our constitution says Congress votes for war, but they stopped doing that after World War II. Now they give broad military authorizations to presidents — They’re happy to do it! Why would they want to commit to yes or no when they can offload the responsibility?

This way, they get all the ra-ra patriotism of “supporting the troops,” by paying for tanks and aircraft carriers, but none of the responsibility for what happens when they’re used thoughtlessly.

Solutions:

No More Free Riding: Americans have the luxury of not voting for the lesser evil and then complaining about the state of the nation and overseas military misadventures. Since 1973, we’ve known there’s no price to pay for poorly conceived military projects, so why pay attention?

But during Vietnam, drawing a “losing number” made draft-eligible men more likely to oppose the War (and vote). In other words, when skin was in the game, they could no longer ignore wars or abstract them into irrelevance. Parents of men likely to be drafted in towns where war deaths had occurred were also more likely to vote. This aligns with other findings that voters punish politicians for losses more than reward them for gains. People need to have skin in the game if you want them to act morally.

We should reinstate the draft and begin mandatory training for at least six months for men and women. If female front-line service is unviable, they should have support roles, with their lives equally disrupted. At least 50% of the troops deployed to war zones should be nonprofessional conscript soldiers. All congresspeople will have at least the initial six months of military training before they vote on military matters.

Our armed forces would be less professional with more draftees, but that’s a worthwhile tradeoff if it stops some poorly executed wars entirely. Of course, the American public is against the reinstatement of the draft by a wide margin. Just like politicians, they prefer to have no skin in the game. I do too — who wants to fight a poorly-conceived war? But we should be forced to.

Reform The Top: No presidential military intervention can last for more than 30 days without a congressional declaration of war or authorization in a stand-alone vote. Each authorization expires after one year and must be renewed. Any congressperson with a child or grandchild eligible for the draft gets 3 times the voting power on military authorizations and war declarations.

Fix Feedback Cycles:

Iteration is the way we’ve solved most of humanity’s problems.

Try something. Didn’t work? Try something else.

But government decision makers have feedback cycles that are either glacially slow or nonexistent. This is part of what the politician meant by, “Sometimes it does feel like the wheel isn’t attached to the rudder anymore.”

When the $42.45 billion Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program was established in 2021, the goal was expanding rural broadband access. As of 2025, no projects have begun construction. Funding is held up in an interminable bureaucratic hell. The congresspeople who voted for it are mostly long gone. They can’t iterate because there was no feedback at all.

The same solution of empowering yes-sayers with heavy rewards and penalties should fix this too.

Fix Financial Suicide

"Equal stakes do not produce equal pressures. The protective tariff is well established because large areas of adverse interests are too inert and sluggish to find political expression."

— E.E. Schattschneider, Politics, Pressures and the Tariff

If you want a perfect example of the “Concentrated Benefits, Dispersed Costs,” quagmire at the heart of so many problems, look no further than the way average Americans vote in relation to economic policies.

Workers are happy to benefit at the expense of both their companies and fellow citizens. They might do this through a union seeking better pay and benefits, but also through supporting tariffs. Economists demonstrate that tariffs hurt the economy and all consumers, but do create jobs in certain industries and increase profits for those companies. Workers often vote and act to exploit this.

A way to partially counteract this is giving workers three ways to benefit instead of one — to give them more skin in the game in more places.

Regular Wages/Benefits: Many Americans are deluded about their prosperity, but increasing it directly through job compensation will always beckon.

Employee Ownership: Government incentives and tax breaks can get companies to vest employees with voting or nonvoting shares of their companies. Even if employees don’t get as big of a wage increase as they’d like, they still benefit if the company increases in value. Even if the company builds a new plant overseas, they still benefit.

Stock Market Exposure: Only 61% of Americans own stocks. If the market tanks the rest aren’t hurt; if it climbs they don’t benefit. Is it any surprise that they vote in ways that will benefit them and hurt the market? The government should have a policy of automatic 401(k) creation and auto-investment for all Americans, with the government seeding the accounts at birth with some funds and providing a small match.

Humans aren’t always rational, but after seeing how personal action and political madness hurt their interests, they may see things differently.

Incentive and Disincentive:

There are a thousand applications for skin in the game, but it all comes down to this — get the people who say yes or no to put more skin in the game without generating conflicts of interest. You don’t want to give your judges bonuses for each person they put in jail, for instance.

If we’re shrewd, we can get our leaders to pry us free of these intractable quagmires.

One of the best ways to do that is to make sure that the decision makers are surrounded by the people whose lives they’re changing.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

In addition to the points made in that article, In 2024, the median Millennial had, adjusted for inflation, about 25% more wealth than Gen Xers and baby boomers did at a similar age, according to a St. Louis Fed analysis. At the same time, for all the complaints about housing, it’s now slightly cheaper than it was in 2000 on a time-pricing basis. Medical care, childcare, and college are more expensive, but there’s no direct connection to the actions of particular generations here.

Skin in the game is critical. So much is kicking the can of consequences down the road. Like our physical health, it's just going to suck more to get back to a healthy standard of life.

Exactly. Change the incentives change the system. Bureaucrats are not evil, theyre just thoughtless, very skilled at dehumanizing everyone who is not beneficial to them, and always act in self interest.

Evil is an unchecked system. Chuck Mangione accomplished nothing by shooting that CEO.

However, when a system or institution does harm, individuals should be held accountable. Not just pay fines and do it all over again.