I woke to a wall crashing down on me.

Choking on wet soot, I shoved the broken chunks off me, threw my feet over the edge of the bed, and splashed down in shin-deep water. Bleary-eyed but shocked to wakefulness, I watched the water line rising up my leg.

Ohhhh shit.

It was October of 2015, and in a moment I’d gone from a happy life to teetering on death’s door in a Texas flash flood. Stormwater surged outside my window, my rented guest house creaked and groaned, and my end had never been closer. Oddly enough, I was about to learn a valuable lesson that would change my life forever.

A Pocket of Life

The water kept rising. Treading frigid water, I eyed the rapidly dwindling air pocket between the water line and the ceiling. The tiny stream behind my home had become a river, raging against the building, churning against old pines. The stretch of yard between my guesthouse and the main one was a chest-high torrent filled with tree trunks hurtling past with the force of battering rams.

Shivering but weirdly calm, I figured there were three possibilities: the rest of the guesthouse would collapse and I’d die, the water would keep rising and I’d drown, or I’d hurl myself out the window and drown outside. None of my options looked good.

But I didn’t die. The water stopped rising a few inches from the ceiling so I could crane my neck up, tread water, and sip the air. An eternity seemed to pass as I bobbed in this pocket of life, the old guesthouse groaning around me.

A motorboat came flying through the swells a few hours later, dodging tree trunks. The firefighters pulled up to my window like I was manning a scuba drive-through. I scrambled aboard, exhausted but happy to be alive.

Short Term Wisdom

"We are always complaining that our days are few, and acting as though there would be no end of them." — Seneca, On the Shortness of Life.

Everything felt surreal after the flood. I was deliriously grateful for the little things. A comfortable bed, my friends, taking a walk – they’d been imbued with a new glow.

I sat up at night, rethinking my existence in light of this brush with death. It felt meaningful, and I tried to figure out why.

It hit me: I’d escaped the flood but death’s proximity was the same. An out-of-control truck on the highway, a shooter, or some fluke disease might end me just as readily as that flood, and just as randomly. Death always looms, but I acted like I’d live forever, barely paying attention. It was stupid.

Being forced to acknowledge my finite supply of days made each one sweeter. It changed how my mind worked and what I wanted to do with my time.

This isn’t just my experience.

After living through a California earthquake that killed dozens of people, a study found survivors shifted away from extrinsic goals like earning money, acquiring possessions, and having people like them, and towards intrinsic ones like building relationships and seeking to accomplish what they found meaningful1. Other studies have found similar positive psychological shifts stemming from brushes with death.

But there’s a problem: not everyone is “lucky enough” to almost die, and even if they are, their enlightenment won’t last.

Backsliding:

A few weeks after the flood I was back to normal, my gratitude vanished.

I knew something was wrong with that; my ingratitude was an insult to the gift of life. I struggled with that, but what can you do when you fail to feel gratitude when you know you should experience it?

I’d read Stoic philosophy since my teens and was familiar with their exploration of death. I’d experimented with Stoic “death exercises” but now decided to get serious with them. I committed to spending a few minutes each day reframing my life from the perspective of my inevitable death.

It worked. Much of the gratitude I experienced after the flood returned. In the years since I’ve developed several habits and rituals forcing me to face death again and again, and I’m better for it.

Psychologists have found reframing our lives in relation to death — as long as it doesn’t become a morbid preoccupation — changes people for the better.

Firefighters risk their lives to save others and frequently see people die in fires and accidents. Some research connects this stress to degraded job performance. But when asked to reflect on death logically and deeply, firefighters become more safety conscious, conscious of the prosocial aspect of their career, and concerned with the welfare of others. They also report more life satisfaction2.

The Power of Memento Mori:

Death is one of the greatest tools for human happiness. If it didn’t exist, we’d have to invent it.

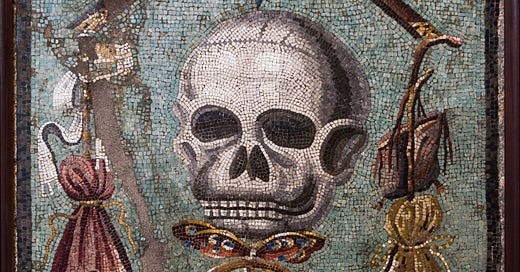

The ancients knew this. “Memento mori,” or “remember death,” reminders were everywhere in the Classical, Medieval, and Renaissance eras. It was in the art, the literature, and the philosophy.

Why? Let’s focus on just one reason.

Every joy loses its savor. This is one of the tragedies of human existence — the so-called hedonic treadmill. Win the lottery, marry your sweetheart, get promoted — you’re happier for a while but inevitably return to baseline.

Dumb luck will make every fool happy sometimes, but since we’re stuck on the hedonic treadmill, contentment takes discipline and intention. It’s a choice. We stay happy not by achieving more, but by being grateful for what we have. That’s easier said than done.

I’m not naturally cheerful — I’ve always leaned cantankerous, and it takes effort to keep myself from a kind of numb resignation. Death, not external things, is one of the most effective means I’ve found to counter my natural disposition.

Strategy One: Tracking Death’s Approach

“You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.”

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 2.11

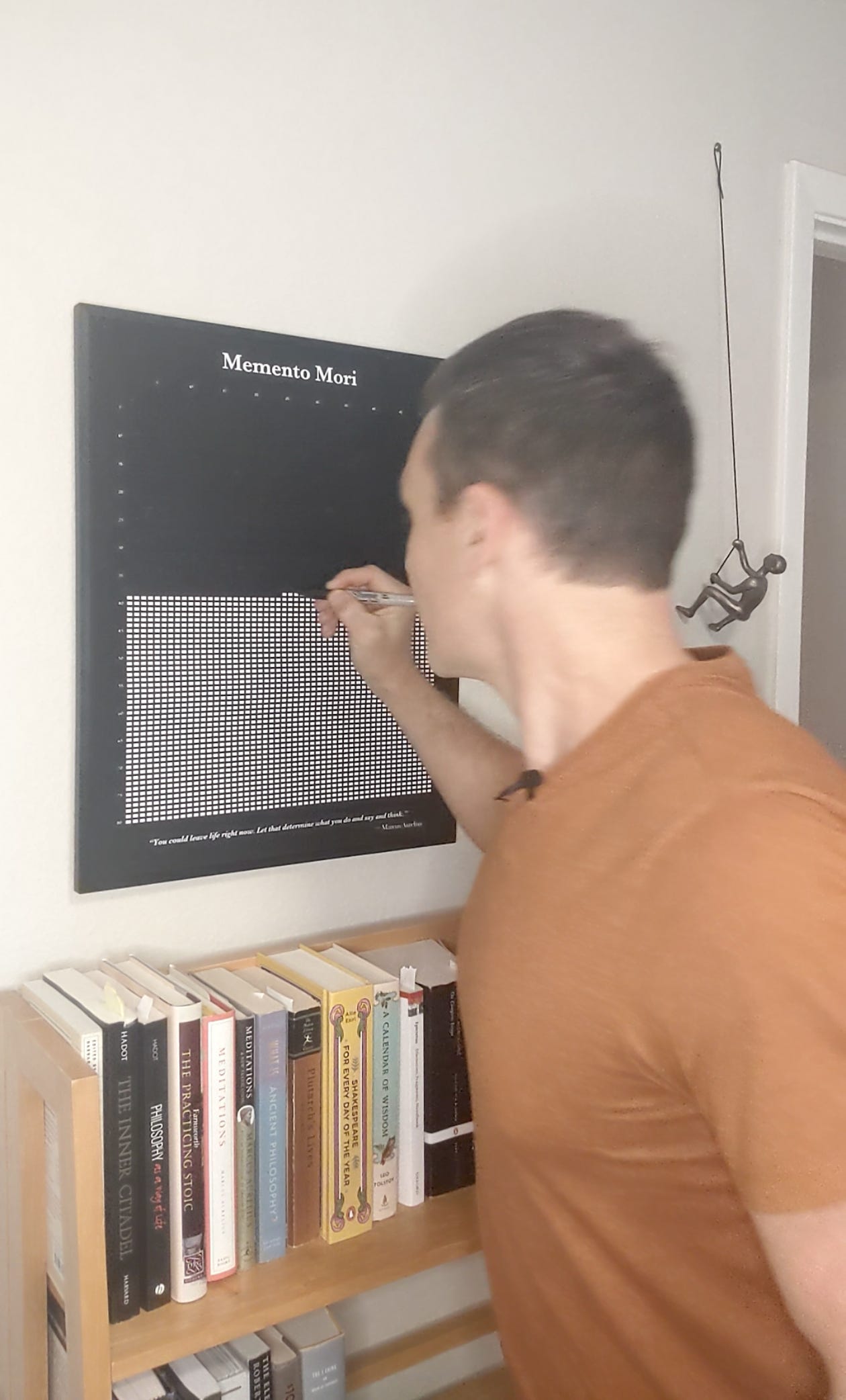

One of my best creations is my Memento Mori Calendar.

I’ve ritualized it: every Sunday I go to my calendar and look at the dwindling supply of weeks left before death claims me. I fill in another box and watch my life receding into darkness.

When my end is so starkly presented, I’m forced to ask questions. How much bullshit have I let creep into my life? Am I playing the only game that matters? Am I devoting time to the most important things?

Thoughtlessly checking off boxes is easy, so I force myself to treat this like a significant ritual rather than the equivalent of doing laundry. Some people visit their church. I visit death. When I do, it never fails to bring me clarity and gratitude.

If you’d like to use the calendar I created, you can get it by supporting Socratic State of Mind as a paid subscriber.

Strategy Two: The Last Time

“The sea is calm now, but do not trust it: the storm comes in an instant. Pleasure boats that were out all morning are sunk before the day is over.” — Seneca, Letters on Ethics, 4.7

There’s a beautiful trail I take from my home in Austin down to Lady Bird Lake. It’s one of the things that drew me to the neighborhood.

But familiarity breeds contempt, and I soon began taking the trail for granted. Every privilege becomes mundane this way. Luckily, life’s endings are the greatest reminders of a things value, and we need not wait for an actual end to benefit from them.

When I walk the trail I force myself to look at the stately old live oak trees, their strange horizontal limbs brushing the ground. I watch the grackles and hear their odd staccato blasts, like the feedback of an amplifier.

This might be the last time you walk this trail, I remind myself. You might have to move, or you could become bedridden and unable to hike.

It’s true, and acknowledging it forces me to have a deeper “last-time experience,” with the walk, and see it with “first-time eyes.” Every good thing ends. Letting the ending catch you unprepared is foolish.

These are the things I say to myself: One day your old junker car will die and no longer carry you around this fantastic world. Your health has been stolen by disease before, and one day it will be again, and on that day you may not recover. Adolescence is already gone, and middle age and its physical prowess will flee too. The infirmity of old age will arrive, beyond which lies only the shores of death.

Every day, every stage of life, has something to be grateful for, and it the end of that thing that allows us to savor it.

Strategy Three: The Hardest People

“If you think you’re enlightened, go spend a week with your parents.” — Ram Dass

Romantic partners, family, friends — loved ones can be the hardest to endure. They can get under our skin like no stranger or coworker ever could.

I’m naturally irascible, so perhaps too easily irritated by loved ones. But I’m well aware that life would be a hollow thing without them. Where would I be, and what savor would life have, without the people I share it with?

But awareness is one thing and happily enduring peoples’ flaws quite another. Luckily, death (alongside reanchoring) once again comes to our rescue.

Before I see irritating people I love, I remind myself: This might be the last time you see them.

It’s a simple truth, but the implications are considerable. If I lose my cool and snap at them, or an argument breaks out, this conflict might be our last memory. If one of us dies before we meet again, will I be happy I ended the relationship with conflict? Yes, maybe they’re thoughtless, have odious political views, or make bad decisions that spill out of their life and disrupt mine. But is that all they are?

When I consider a relationship in light of its inevitable end, the memories we’ve had, how we’ve loved each other, and how much life would be diminished without them heaves into view. I’m grateful and happily put up with more annoyance than I’m normally inclined to. It just doesn’t matter that much.

Our loved ones may be gone tomorrow. Let that determine what to do.

Lykins, E. L. B., Et al. Goal Shifts Following Reminders of Mortality: Reconciling Posttraumatic Growth and Terror Management Theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(8), 1088–1099.

Yuan Z, et al. Memento Mori: The development and validation of the Death Reflection Scale. J Organ Behav. 2019; 40: 417–433.

I struggle with the relatives. Covid sorted out some irrational things about these “loved ones”. Thankfully, not having any social media accounts and realizing the gravity of the whole affair I minded my beeswax. I tend to red line people once they exhibit irrational behavior.

Many years ago it became apparent to me with a question: why do I treat the ones I love (sometimes)crappy? Well it is in my nature to test the waters, but the simple answer is

“Because I know what I can get away with” before relationship damage is a byproduct.

Testing the water when I know the depth.

Because we can, is the full stop to correct where I’m venturing. Just being aware.

The whole relative thingy for me ends up

With another question: Because we’re related does that somehow mean I have to tolerate their bs behavior? No.

Would I form a friendship with this type? No. So, that is the way it must be for me.

Much appreciated, your thoughtful essay!

Sincerely,

Charlie

Gratefulness is like a muscle. It needs to be exercised. Well worth the effort. Jung thinks getting irritated at others requires us to look deep into our own flaws. Charles Krauthammer was grateful he stared death in the face every day. He felt it made him love and appreciate the life he had.