What! Gratitude again? Didn’t you just write about this, Andrew?

I know. I know.

But I have one last thing to tell you about gratitude. Hell, to tell myself. Because when I’m writing to you I’m usually reminding myself how to be less foolish.

My last article discussed bypassing a common problem: the things we’re intellectually grateful for often generate little or no emotion, and thus no real gratitude.

I hope you found my workaround useful.

But here’s the thing — even if you master it, continuously hammering on the same gratitude topics leads to diminishing returns.

How many times am I going to be grateful for my wonderful girlfriend, my home, my local park, air conditioning, running water, etc? I find it best to let them “rest” a bit and return to them when they’re fresh.

If you’re running out of steam on appreciating the same old topics, then you should consider the untapped potential of “negative gratitude.”

Marcus’s Negative Gratitude

This isn’t my idea. It runs through Stoicism and we see Marcus Aurelius using it in Meditations many times. The idea is to be grateful for the unpleasant, undesired things that happen to us.

He gets at the spirit of it when he says, “…and convince yourself that everything is a gift from the gods, that things are good and always will be…”

Everything? Really? Seems like a tall order.

There are multiple ways to instill this mode of thinking, but let’s discuss the simplest: considering how undesired fates make us better, more resilient humans.

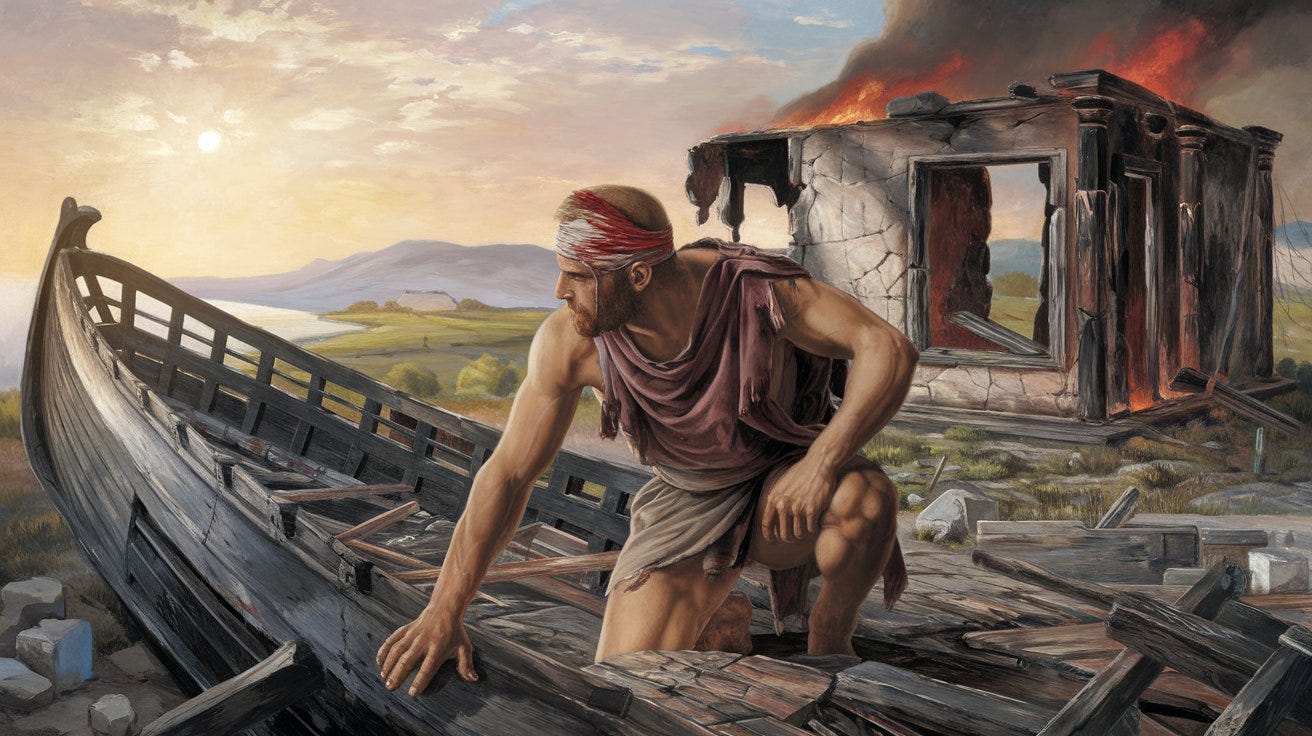

You can be grateful for tragedies the same way you’re grateful for the heavy weights you lift — both strengthen you. The difference is that you choose to lift weights, and bad fortune chooses you. The inescapability of dispreferred fates is useful, since it’s easy to stay comfortable and shirk personal growth the same way people shirk maintaining their bodies.

To overcome fate we must become more just, courageous, moderate, and wise. These constituents of virtue can be deployed against future adversity in the same way increased muscle mass is deployed against increasingly heavy burdens. Both make us stronger, and life easier.

We could let tragedies break us, of course. But that’s a choice. If we choose to not be broken, and instead use tragedies as catalysts for growth, then they’re a cause for gratitude and maybe even celebration.

Spontaneously appreciating unwanted things popping into our reality is the ultimate goal, and a key part of the great Stoic invincibility game. But it’s easier to learn this skill by appreciating already-overcome misfortunes that benefited us.

My Goldmine of Undesired Fates

I have an autoimmune disease called colitis. When it got really bad around age 19 it hurt like hell and caused me all kinds of psychological pain. I felt broken and doomed. To overcome it I learned to be more disciplined in my eating and lifestyle than anyone around me. The discipline of keeping my colitis in remission spilled into the rest of my life, making everything better. I’m thriving because I have a horrible autoimmune disease. Funny how that works.

I struggled to read and do math as a child. Hell, I just plain sucked at learning. Tutoring didn’t help. Being designated “learning disabled,” and going to special classes didn’t help. But ironically, these problems forced me into different paths that made me better at everything. By 6th grade I was the best reader in the class, and while I’m no math superstar, I was able to make it work. I also embraced classical mnemonic techniques which brought me from dreading tests to frequently acing them by the end of college.

Good romantic relationships ending? I drew useful lessons from each. Obesity? Beating it made me better. I have horrible allergic reactions to numerous things, but staying on top of them keeps me focused in many areas of life. My temper? Struggling against it gave me perspective on the entirety of my life.

This isn’t about being delusional. Horrible fates aren’t pleasant. Losing my father, romantic heartbreak, and managing numerous health conditions is something I wouldn’t seek out. But each increased my resiliency, and its only reasonable to be grateful for what they’ve done for me.

This practice helps us look at reality as Marcus did. We too can stand up and take more than our fair share of suffering, just as we’ve done in the past:

“You say — ‘It’s unfortunate that this has happened to me.’ No. It’s fortunate that this has happened and I’ve remained unharmed by it — not shattered by the present or frightened of the future. It could have happened to anyone. But not everyone could have remained unharmed by it.”

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 4.49a

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

I feel your pain on the autoimmunity. It was a hell that led to a level of gratitude I never thought possible. After all the foods I have had to strip away, the taste of a raspberry is enough to drop me to my knees in gratitude

I find this essay incredibly valuable! These types of situations are so powerful to reflect on because we have skin-in-the-game. They actually DID impose the hardship, yet we ARE growing from the experience. When we realize this and help others understand this, we have soul-in-the-game! Thanks for this Andrew!