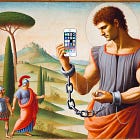

Thomas Jefferson failed, and I’m a fan of the way he did it.

With eloquence that shook the world, he boldly proclaimed that “all men are created equal,” in the Declaration of Independence…and then kept men in chains to support his opulent lifestyle.

He lambasted John Adams’s crackdown on newspapers and opposition politicians, and then suppressed free speech as president.

He sympathized with the Native Americans, insisting they were “in body and mind equal to the whiteman," and then took their land, destroyed their culture, and expelled them beyond the Mississippi.

He supported rigid adherence to the Constitution and limited presidential power, and then exceeded the limits of the presidency and the Constitution by purchasing the Louisiana Territory.

Whether you think Jefferson was an inveterate hypocrite or merely a pragmatist doing the best he could, he clearly fell short of his publically stated ideals.

And it was fantastic.

We need look no further than Jefferson’s neighbor to understand why.

Your Words Echo

"First say to yourself what you would be; and then do what you have to do. For in nearly every case, hypocrisy is born of disconnection between what we claim to be and what we actually practice." — Epictetus, Enchiridion, 49

Edward Coles was Jefferson’s neighbor in the foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, though born one generation behind.

The younger man idolized Jefferson and the founders. He read their words, believed in the better future they envisioned, and as a starry-eyed child learned how they fought the world’s greatest empire to a standstill and gained independence for the nation.

He believed them. And then he met them.

While serving as an aid to President James Madison in 1814, he wrote a bold but polite letter to Jefferson — How, he wanted to know, could Jefferson claim to believe in universal equality while simultaneously owning slaves?

To his credit, Jefferson answered this gentle call out. He claimed to be too old to change his ways and free his slaves. Nor would he campaign to end slavery.

“This enterprise is for the young; for those who can follow it up, and bear it through to it’s consummation.” — Jefferson’s Letter To Edward Coles, Aug, 1814.

Coles also urged President Maddison to free his slaves, but had no more luck with him. Both founding fathers had, sadly, become enslaved to their slaves.

Coles decided to take matters into his own hands. After his father died and he inherited 12 slaves (which grew to 19 through births) and a 782-acre plantation that wasn’t viable without slave labor, he decided to leave the genteel life of a southern aristocrat behind.

He traveled to Illinois with his slaves, freed them (at a loss of an inflation-adjusted $1.5 million), gifted each freed family a 160-acre farm, and found work as a land register and surveyor in the rugged territory. Coles, in other words, did what Jefferson and Maddison never could — paid a price for his ideals.

Joining the Illinois Constitutional Convention at Kaskaskia, Coles fought off attempts to enshrine slavery in the Constitution and got an anti-slavery clause added. When a slaver ran for Governor in 1822 on a platform of removing the clause, Coles entered the race, narrowly winning the governorship and ensuring the state would never allow slavery.

Hypocrisy’s Echo:

But perhaps Coles’s greatest moment came in 1831, after his term as governor was over. He’d been corresponding with Jefferson’s grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, subversively feeding him back his deceased grandfather’s rhetoric and ideals.

Like Coles, Randolph became a believer in what had previously been mere hypocrisy. He stood before Virginia’s General Assembly in 1831 and called on the representatives to ban slavery. The measure was narrowly defeated, and Randolph did not unilaterally free his slaves. But slowly, slaveowners came to recognize that a corner had been turned. The war to spread slavery was floundering, and they were now fighting a rearguard action to maintain it.

The whole nation watched Coles and his contemporaries live up to their ideals, and it would not be forgotten. A civil war lay ahead, but the ideological groundwork that would see it through was laid.

What Is Hypocrisy?

There are two paths to hypocrisy:

You try to live up to ideals you hold but fall short, sometimes publically in a way that invites derision.

You feel straightjacket by others’ ideals but profess to hold them to escape censure or gain advantage, all the while failing to act accordingly.

By this metric, everyone is a hypocrite sometimes. Who doesn’t fall short of their ideals? It’s just a matter of how publicly we fail.

And as to the second bucket? Consider de La Rochefoucauld:

“Hypocrisy is the homage vice pays to virtue.”

— François de La Rochefoucauld, Epigram 218

Even evil men deceitfully espousing high ideals for personal gain pay them homage by admitting they exist as higher standards. They helps cement them in place as the benchmark.

Jefferson cinched the “Overton window1” a little tighter by pushing virtuous, viral ideas on the world. His actions were hypocritical, but because his words were accepted as the founding ideals of the country, it put slave owners in an awkward position. They could either pay lip service to an ideal underming the slavery they depended on and damage their cause, or they could come out as being against everything the revolution was about.

Try A Little Hypocrisy On For Size

Jefferson's failure to live up to his ideals wasn’t the only possible outcome. Three decades of research into “induced hypocrisy” show it often helps people improve their behavior2.

It works like this:

Researchers have subjects write a letter or record a video urging others to adopt a behavior.

Participants are asked to recall their past transgressions of this preached message.

Subjects experience uncomfortable cognitive dissonance and want to escape it, and so are more likely than controls to change their behavior to align with their espoused belief.

But even if you pooh-pooh this effect as not enough, what’s the alternative?

Do we want politicians and public figures to abandon the pretense of aspirational virtue? I’d argue that’s where we are now, and it’s not pretty.

Someone may hold aspirational beliefs while staying silent in the face of injustice, but society suffers in this moral vacuum. We need people reinforcing our often-tenuous higher ideals.

Everyone is better off when individuals risk publically falling short, and doing so incentivizes them to follow through.

Being watched is a powerful behavior modifier.

My Favorite Hypocritical Echo

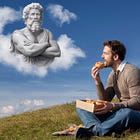

Accusations of hypocrisy will forever tarnish the reputation of the Stoic philosopher Seneca, one of the great thinkers and writers of antiquity.

While espousing the high-minded virtues of justice, courage, and moderation, he abetted the megalomaniacal emperor Nero. Many accusations against him are unfair, and Seneca handed us a model for navigating hypocrisy risk.

Through all his writings, Seneca is clear: he’s a failure trying to do better.

“I’m not so shameless as to undertake to heal others while sick myself. It is rather as if we were lying in the same hospital room; I’m talking with you about our common illness, and sharing remedies. So listen to me as though I were talking to myself. I’m letting you into my private place, and am examining myself, using you as a foil.” — Seneca, Epistles, 27.1

By admitting fallibility while glorifying a higher standard, Seneca’s ideas became beloved by Christians to such an extent that the early church leader Tertullian referred to him as "Our Seneca." His ideas were adopted into Christianity and the Christian moral revolution that’s bettered the world over the last few centuries is at its heart a Senecan one.

Seneca informed the chivalric tradition of the Middle Ages, the writings of Montaigne, and the Enlightenment philosophers Rousseau and Voltaire. It was these philosophers who inspired Thomas Jefferson to boldly proclaim that “all men are created equal,” an echo that took 1,700 years to bounce back.

So in the end, by espousing grand ethical ideas they couldn’t live up to, Jefferson and Seneca changed the world by setting a higher bar that others would live up to.

Seneca knew exactly what he was doing:

“I am working for posterity: it is they who can benefit from what I write. There are certain wholesome counsels, which may be compared to prescriptions of useful drugs; these I am putting into writing; for I have found them helpful in ministering to my own sores, which, if not wholly cured, have at least ceased to spread.” — Seneca, Epistles, 8

In the end, most good things come from standing on the shoulders of giants, getting up on our toes, and reaching just a bit higher than feels comfortable. With any luck, society will catch up to us in the end, even if we fall off those shoulders in the attempt.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you enjoyed this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

The subjects, arguments, and opinions a culture considers acceptable at any given time. The Overton window often shifts slowly, but sometimes leaders pry is wide open or slam it almost shut in a very short window of time.

Daniel Priolo, et al.. Three Decades of Research on Induced Hypocrisy: A Meta-Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2019, 45 (12), pp.1681-1701.

I’ve always seen a distinction between someone who does NOT mean what they preach and those who fail to live up to their ideals. But I’ve never known appropriate terms.

Thanks Andrew. Really enjoyed this - and it underscores a core belief I’ve always held….just because we sometimes fall short of the ideals and standards we set, it does not make them any less worthy…and certainly does not mean they should be lowered to make our fall more bearable. Being a hypocrite is something everyone must wrestle with.