“Jen” Asks: I’ve been reading Stoic philosophy books and like the ideas. Marcus Aurelius is helpful and soothing. But there’s nothing that will help with the disastrous times coming. Global warming is destroying this planet and it’ll be unlivable soon, or close enough. It makes me want to scream in anger and despair at what past generations have done and how little they’ve cared. Do I want to have children in this world and leave them a horrible life? Why even build a life when it’s all coming down? What does Stoicism have to say about an apocalypse?

Andrew Answers:

If something stalks you in the night, the first step is to turn and face it. If you keep walking, too alarmed to turn and see it clearly, you’ll never respond effectively, nor know what the threat is.

“But Andrew,” you say, “I know what we’re facing! It’s an environmental disaster.”

Are you sure you’ve seen this clearly, creeping in the dark? Have you caught a good glimpse, or has an amorphous blob of dread dread taken hold of you?

Let’s not sugarcoat it: Our environment will grow erratic as it warms. Disasters will become more common. Some coastal regions may be submerged and there will be population displacement, economic damage, and negative health consequences.

But expecting an apocalypse or suggesting the planet will become “unlivable” isn’t in line with the mainstream scientific consensus; it’s hyperbolic.

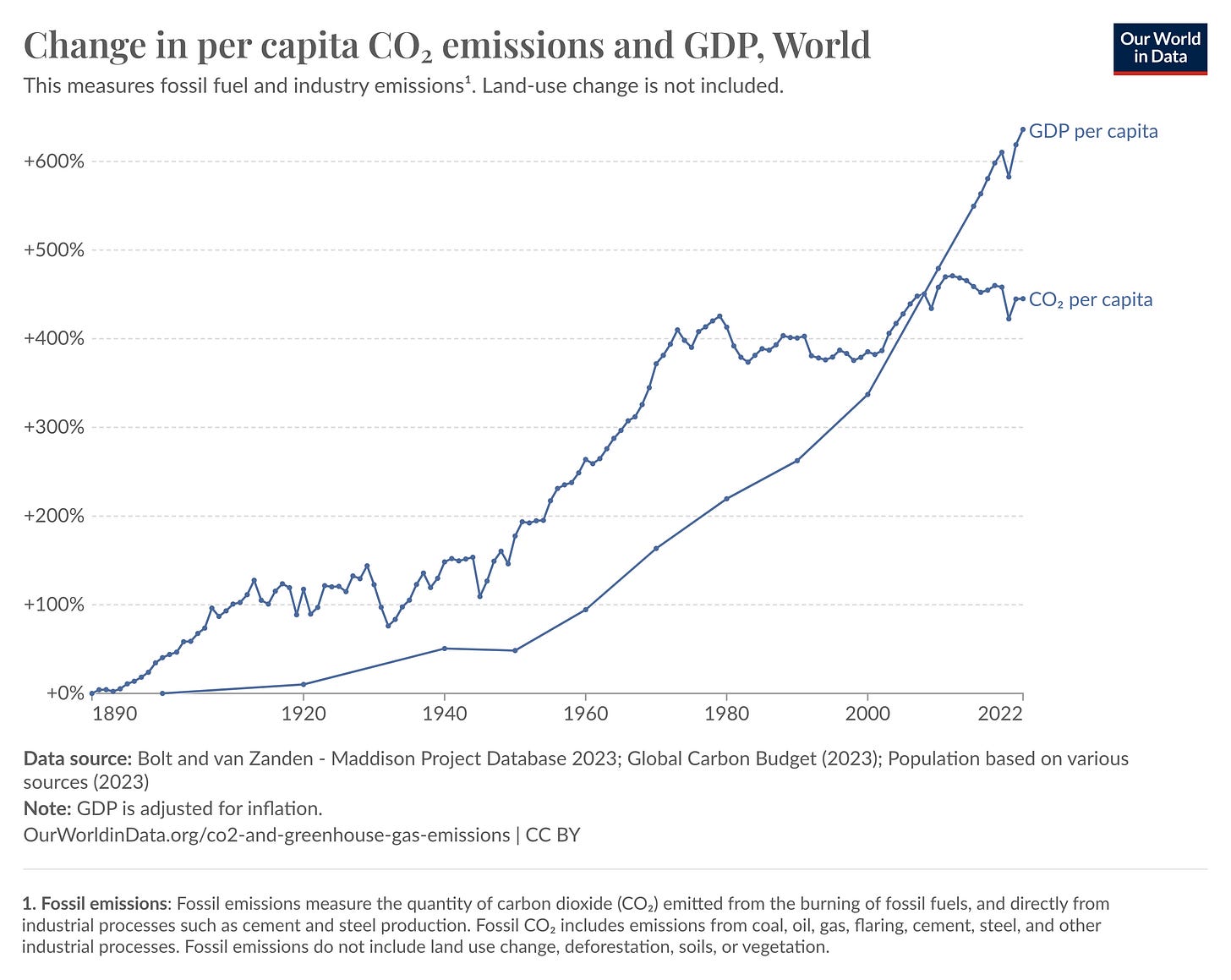

The worst-case doomsday scenarios outlined in the 2010s assumed coal use would continue to increase and carbon-free power would remain expensive. That didn’t happen; coal use in many major economies has plummeted and GDP growth is decoupling from carbon emissions, even after accounting for imported goods. China expects its carbon emissions to peak around 2030 and fall afterward.

So most scientists don’t consider worst-case apocalyptic scenarios plausible anymore.

What’s more promising is that green power prices are plummeting and carbon removal tech may become feasible. If global warming becomes horrendous, we have several unpalatable but feasible and affordable methods of lowering global temperatures, such as temporarily deploying sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere.

The reality of one climate change scenario is bunk anyway. There may be 10 billion humans by 2100. Varied geographies, wealth, individual coping abilities, and government competence suggest 10 billion climate change scenarios. There will be opportunities for good lives for those who keep their heads and remain flexible.

Some Midwestern farmers are utilizing warmer temps to double crop for the first time in history, and that will increase. The loss of sea ice may open the northwest passage for shipping. Green technology research may catalyze unexpected avenues for human flourishing.

But maybe our projections are built on faulty assumptions. Deglobalization would shatter our models. Import tariffs on solar panels would set us back years. Why are so many islands rising higher as sea levels rise? Our assumptions were off, and we don’t know how far off our future assumptions are.

But now that we’ve faced the beast and constrained the amorphous blob of dread to something solid, there’s a bigger issue we have to address.

Why Has This Paralyzed You?

We agree that global warming is a big problem that needs to be addressed.

But why does global warming have your attention among potential threats? For instance, if we assume a 1% annual risk (0.01) of a nuclear war, then the cumulative risk over 100 years is a staggering 63.4%. Maybe a 1% risk is unreasonable, but you see what I mean.

And if we add in all the other risks? AI? Pandemics? War? Asteroid strikes? What about the unknown unknowns, the true “black swans?”

I’m not trying to alarm you but rather wake you to reality — there’s always another threat waiting in the wings. Uncountable dooms loomed over our ancestors; different ones menace us. Our descendants will face threats we haven’t even imagined. To let potential threats paralyze us and make us miserable is foolish. We’re ceding the good life to fear and an endless succession of maybes.

If we put off doing good, making art, being happy, and creating futures for ourselves till not a single cloud darkens the horizon, we’ll never do anything worthwhile.

And there’s another piece here: we don’t know if what we dread will turn out for the worst. I’ve always found the Taoist tale of the farmer who lost his horse soothing:

An old farmer’s horse runs away.

Upon hearing this, his neighbors visit. “Such bad luck,” they say, sympathetically.

“Maybe,” the farmer replies.

The horse returns the next day, leading three wild horses.

“How wonderful,” the neighbors exclaim when they come to see.

“Maybe,” replies the old farmer.

The following day, the farmer’s son mounts one of the wild horses and is thrown, breaking his leg. The neighbors return to offer sympathy: “It’s unfair that all this is happening to you.”

“Maybe,” answers the farmer.

Military officials come to the village the next day to draft young men into the army. They see the son’s broken leg and pass him by. The neighbors congratulate the farmer on how well things have turned out in the end.

“Maybe,” says the farmer.

Before you dismiss this idea, consider nuclear weapons. We say they’re a great evil, but many experts wonder if they’re a counterfactual blessing. Without their assurance of mutual destruction, World War III may have already broken out, killing millions or billions of humans. Maybe a world without nuclear arms would be worse. If we moved aggressively against climate change in 1972 — when Jimmy Carter got his presidential notification memo — would the world be better? There’s no way to be certain where that path would have lead.

How To Live, No Matter What Happens

You’ve been reading Meditations, so you know Marcus focuses on what’s directly under his control. He tried to align his actions and words with virtue (wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation) to the greatest extent possible. He lets go of the uncontrollable.

This is always humanity’s best choice, regardless of what threats loom. So what does that look like?

Let go of hyperbole and see things as they are. Use your reason and your senses to realistically assess reality to the best of your ability.

If you determine that climate change or any other situation should be faced, then virtue may demand you play a role. This might involve changing your life, campaigning for a cause, or starting a career in green technology or climate-friendly farming. Maybe there’s an impactful path only you can see.

Whatever happens, learn to keep your head on straight and don’t give in to despair. Find your handcuffs and live in alignment with virtue.

And what happens when despair comes anyway?

Stoicism is not a facile theory, but a practice. To stay sane and act virtuously, you must practice:

When anxiety comes, do the next right thing.

When bad things happen, mutter this mantra.

When you’re angry, you’re stupid and less effective, and there are better ways to use your energy. Focus on what you control.

Feel gratitude for the little things and the hard things each day

It would be deceitful to tell you everything will turn out as you prefer, but I can assure you that no matter what happens, you can always act with virtue. If you’re a Stoic, that’s enough for a good life.

And if you’re not? Fate is full of surprises. Things might work out better than you could ever imagine.

Thanks for reading Socratic State of Mind.

If you liked this article, please like and share it, which helps more readers find my work.

I need to stop being frustrated by friends who can't stop and say "maybe". Absolutely exhausted from everyone screaming that the sky is falling for 8 straight years.

Looking forward to reading this.